36 Heuristics and the bias-variance trade-off

Summary

- Heuristics, while often associated with errors, can be powerful and effective decision-making tools due to the bias-variance trade-off.

- The bias-variance trade-off suggests that as model complexity increases, bias tends to decrease, but variance (sensitivity to data fluctuations) increases. There’s an optimal level of complexity that balances these two factors.

- Simple heuristics can sometimes outperform more complex decision-making strategies by finding a better bias-variance trade-off, leading to lower overall error despite using less information.

- The “Take the Best” heuristic, which uses cues in order of validity to make predictions, has been shown to perform as well as or better than multiple regression across various environments.

- The gaze heuristic, used for catching balls, demonstrates how a simple rule (maintaining a constant angle of gaze) can effectively solve a complex problem without requiring complex calculations, even if it results in a seemingly biased movement pattern.

36.1 Introduction

Much of the heuristics and biases literature of Kahneman, Tversky and those who followed in their footsteps focuses on the errors that can be caused by using heuristics. However, there are also powerful reasons why we use heuristics in decision making.

One of the strongest arguments for the use of heuristics relates to what is called the bias-variance trade-off.

Suppose you are trying to make a prediction or develop an estimate based on historical data. There is a true underlying process that is generating the data. You plan to build a predictive model that should approximate the underlying process. You have a noisy data sample with which to develop it and you are trying to decide which predictors to include.

For example, you want to predict the level of dropout in a school. You have possible predictors such as attendance rates, family socio-economic status, the school’s average SAT score, and the degree of parental involvement in the child’s schooling. Which of those should you include in your model?

Bias is the degree to which there are erroneous assumptions in your model. The classic case of bias is when you have failed to include a relevant predictor. If you exclude relevant predictors, your predictive model will not include relevant relations between the predictors and the target output you are trying to predict. In the school example, to the extent any of these factors are linked to dropout rates, excluding them can bias your prediction.

However, the inclusion of too many predictors can lead to what is called variance, which is an error that arises because of the sensitivity of the model to fluctuations in the data you use to develop the model. It ultimately involves giving too much weight to irrelevant or marginally relevant information.

For example, if you included the school colours in your model, it may appear to give you a better model due to noise. But as soon as you used that model to make a new prediction, the inclusion of the irrelevant variable would likely backfire.

The following image gives one conception of bias and variance. An unbiased predictor will tend to centre on the target. A low variance predictor will tend to cluster. A low variance, low bias estimate is the best outcome.

However, as the term bias-variance trade-off suggests, you typically can’t choose the minimum bias, minimum variance option. There is a trade-off between the two. As model complexity increases, bias tends to decrease, but variance tends to go up. There is an optimal level of complexity.

The result of this bias-variance trade-off means that heuristics can sometimes be better than more complex decision making strategies. This is not just because they are tractable for the human mind - unlike, say prospect theory calculations or Bayesian updating - but also because they find a better bias-variance trade-off. Despite our focus on how heuristics can cause biases decisions, they can also lead to lower error.

36.2 Simple heuristics

In a chapter in Simple Heuristics That Make Us Smart, Czerlinski et al. (1999) describe a competition between some simple heuristics and multiple regression. Both were used to predict outcomes across 20 environments, such as school dropout rates and fish fertility.

One simple heuristic in their competitions was “Take the Best”. This heuristic operates by working through variables in order of validity in predicting the outcome. For example, if you want to know which of two schools has the highest dropout rate, you ask which of the many possible predictive cues has the highest validity. If student attendance rate has the highest validity, and one school has lower attendance than the other, infer that that school with the lower attendance has the higher dropout rate. If the attendance rate is the same, look at the next cue.

Depending on the precise specifications, the result of the competition across the 20 environments was either a victory for Take the Best or at least equal performance with multiple regression. This is impressive for something that is less computationally expensive and ignores much of the data (or in other words, is biased).

The reason for this success was that the simpler models had lower variance. This enabled lower or similar total error to the more complex models that included all variables.

36.3 Example: The gaze heuristic

As another example of a heuristic in operation, consider the gaze heuristic.

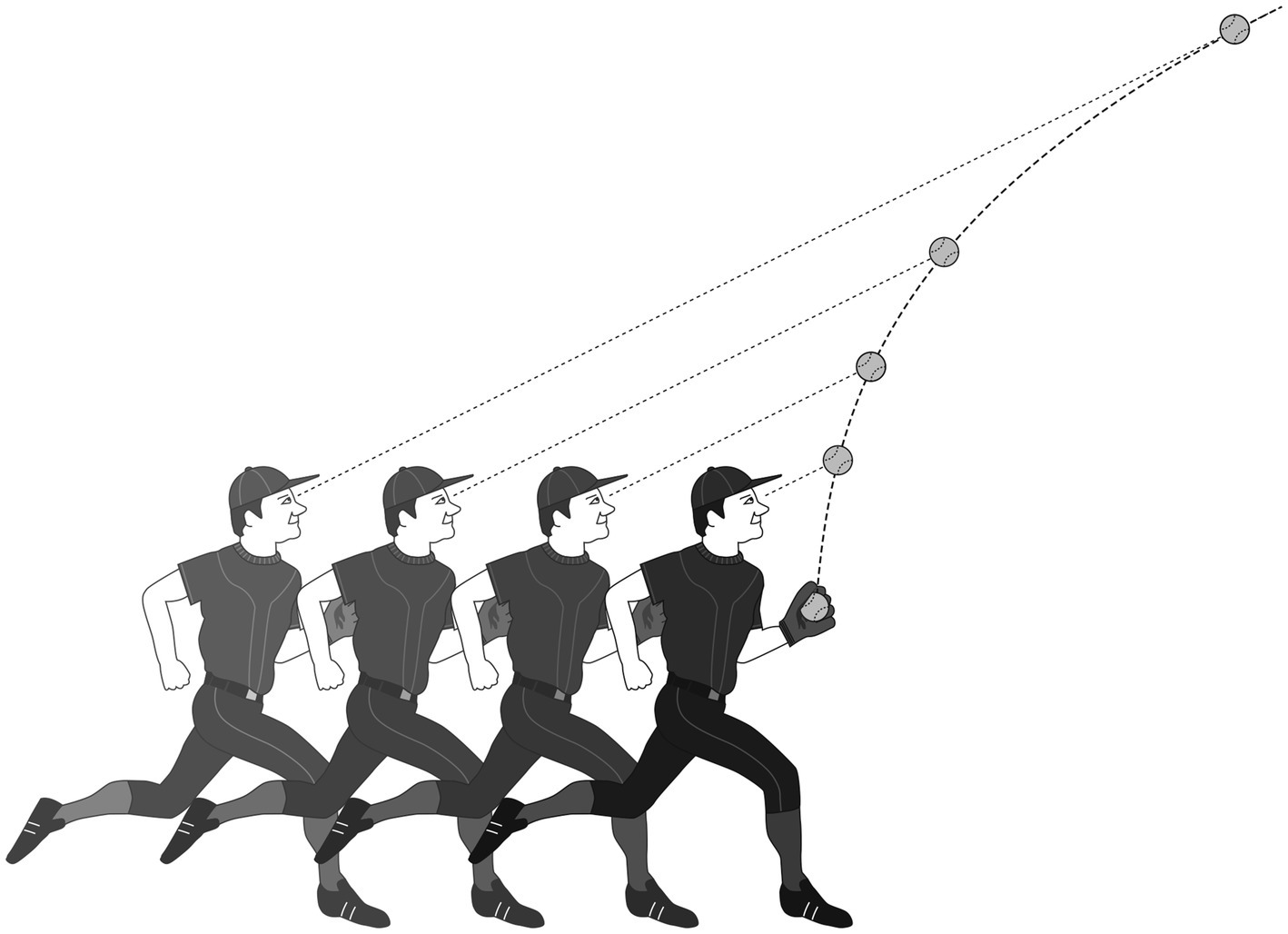

The gaze heuristic is a tool that people - and dogs - use to catch balls. The heuristic is simply this: maintain the ball at a constant angle of gaze. If you move to keep this angle constant, you will end up where the ball lands. Obviously, this is easier than calculating where you should be from the velocity of the ball, the angle of flight, the effect of wind resistance and so on.

But it results in a strange pattern of movement. Suppose you are close to the point where the ball is first hit into the air. As it rises you will tend to back away from the ball. As it then starts to fall, you will move back in. If it is hit up to the side of you, you will move to the ball in a curve. If you examine the path you took to catch the ball, you might call the curve a bias. However, it is actually the result of a very effective decision-making tool.

There are also some circumstances where the gaze heuristic works better than others. It tends to work best when the ball is already high in the air. If you catch sight of a ball hit straight up before it has risen far, using the heuristic for its entire flight could require first running away from the ball and then toward it.

Understanding this is a much richer understanding than saying that the catcher is biased because they did not run straight to where the ball was going to land. It also points to the power of heuristics. Try to train someone to run straight to where a ball will land and watch them fail. Don’t see heuristics as poor cousins of “more rational” approaches.