30 Intertemporal choice exercises

30.1 Exercise or television?

Olga and Paul can choose one of the following options:

Exercising at t=0 (utility = 0) and being healthy at t=1 (utility = 30).

Watching television at t=0 (utility = 15) and being unhealthy at t=1 (utility = 0).

a) Olga discounts the future exponentially with \delta=2/3. At t=0, what is Olga’s utility of exercising and watching television? What does Olga do?

\begin{align*} U_0(exercise)&=u(x_0)+\delta u(x_1) \\ &=0+\frac{2}{3}\times 30 \\ &=20 \\ \\ U_0(television)&=u(x_0)+\delta u(x_1) \\ &=15+\frac{2}{3}\times 0 \\ &=15 \end{align*}

Olga gets higher discounted utility from exercising, so chooses to exercise.

b) Paul discounts the future quasi-hyperbolically with \beta=3/4 and \delta=2/3. At t=0, what is Paul’s utility of exercising and watching television? What does Paul do?

\begin{align*} U_0(exercise)&=u(x_0)+\beta\delta u(x_1) \\ &=0+\frac{3}{4}\times \frac{2}{3}\times 30 \\ &=15 \\ \\ U_0(television)&=u(x_0)+\beta\delta u(x_1) \\ &=6+\frac{3}{4}\times \frac{2}{3}\times 0 \\ &=15 \end{align*}

Paul is indifferent between the two options, so could choose either.

30.2 Today or tomorrow?

Terry and Andy are given the choice between the following three options:

A (utility of 3 at t=0)

B (utility of 4 at t=1)

C (utility of 5 at t=2).

a) Suppose that Terry discounts the future exponentially with 0<\delta<1. He is indifferent between A and B at t=0. What does this tell you about Terry’s \delta?

The utility of A and B must be equal.

\begin{align*} U_0(A)&=U_0(B) \\[6pt] 3&=\delta 4 \\[6pt] \delta&=\frac{3}{4} \end{align*}

b) Andy discounts the future quasi-hyperbolically with 0<\beta<1 and 0<\delta<1. At t=0, Andy is indifferent between A and B. What does this tell you about Andy’s \beta and \delta?

The utility of A and B must be equal.

\begin{align*} U_0(A)&=U_0(B) \\[6pt] 3&=\beta\delta 4 \\[6pt] \beta\delta&=\frac{3}{4} \end{align*}

We cannot determine anything else about the two as the discounting between t=0 and t=1 is a function of both the short-term and exponential discount factor.

c) At t=0, Andy is indifferent between B and C. What does this tell you about Andy’s \beta and \delta?

The utility of B and C must be equal.

\begin{align*} U_0(B)&=U_0(C) \\[6pt] \beta\delta 4&=\beta\delta^2 5 \\[6pt] 4&=\delta 5 \\ \delta&=\frac{4}{5} \end{align*}

d) Combining the results of (b) and (c), compute Andy’s \beta and \delta?

We have already computed:

- \delta=\frac{4}{5}.

We also know:

- \beta\delta=\frac{3}{4}

Accordingly, substituting (1) into (2):

\begin{align*} \beta\frac{4}{5}=\frac{3}{4} \\ \beta=\frac{15}{16} \end{align*}

30.3 Today or tonight?

Kate and Jack have utility function u(x)=x and can choose one of $3 now (t=0), $4 this afternoon (at t=1), or $7 tonight (t=2).

a) Kate is an exponential discounter with \delta=\frac{1}{2}. What does she choose?

We calculate discounted utility of each option and choose the highest.

\begin{align*} U_0(\$3)&=3 \\[6pt] U_0(\$4)&=\delta\times 4 \\ &=2 \\[6pt] U_0(\$7)&=\delta^2\times 7 \\ &=\frac{7}{4} \end{align*}

Kate chooses the $3 now.

b) Jack is a hyperbolic discounter with \beta=\frac{1}{2} and delta=1 what does Jack choose?

You calculate discounted utility of each option and choose the highest.

\begin{align*} U_0(\$3)&=3 \\[6pt] U_0(\$4)&=\beta\delta\times 4 \\ &=\frac{1}{2}\times 1 \times 4 \\ &=2 \\[6pt] U_0(\$7)&=\beta\delta^2\times 7 \\ &=\frac{1}{2}\times 1^2 \times 7 \\ &=3.5 \end{align*}

Jack chooses the $7 tonight.

Although Jack is a hyperbolic discounter, the short-term discount factor is only applied once.

c) This afternoon (t=1) comes and Jack reconsiders his decision. Should he take $4 this afternoon (t=1), or $7 tonight (t=2). What does Jack decide?

We calculate discounted utility of each option and choose the highest.

\begin{align*} U_1(\$4)&=4 \\[6pt] U_1(\$7)&=\beta\delta\times 7 \\ &=\frac{1}{2}\times 1 \times 7 \\ &=3.5 \end{align*}

Jack changes his mind and takes the $4 immediately.

d) Why did or did not Jack change his mind?

At t=0 the difference in discount between the $4 at t=1 and $7 at t=2 is \delta. Both are discounted by \beta as neither is immediately available. However, at t=1 the difference in discount between the $4 and $7 is \beta\delta. The $4 is no longer subject to the immediate discount of \beta, making it relatively more attractive.

e) Show the answers to parts a) to d) using a diagram.

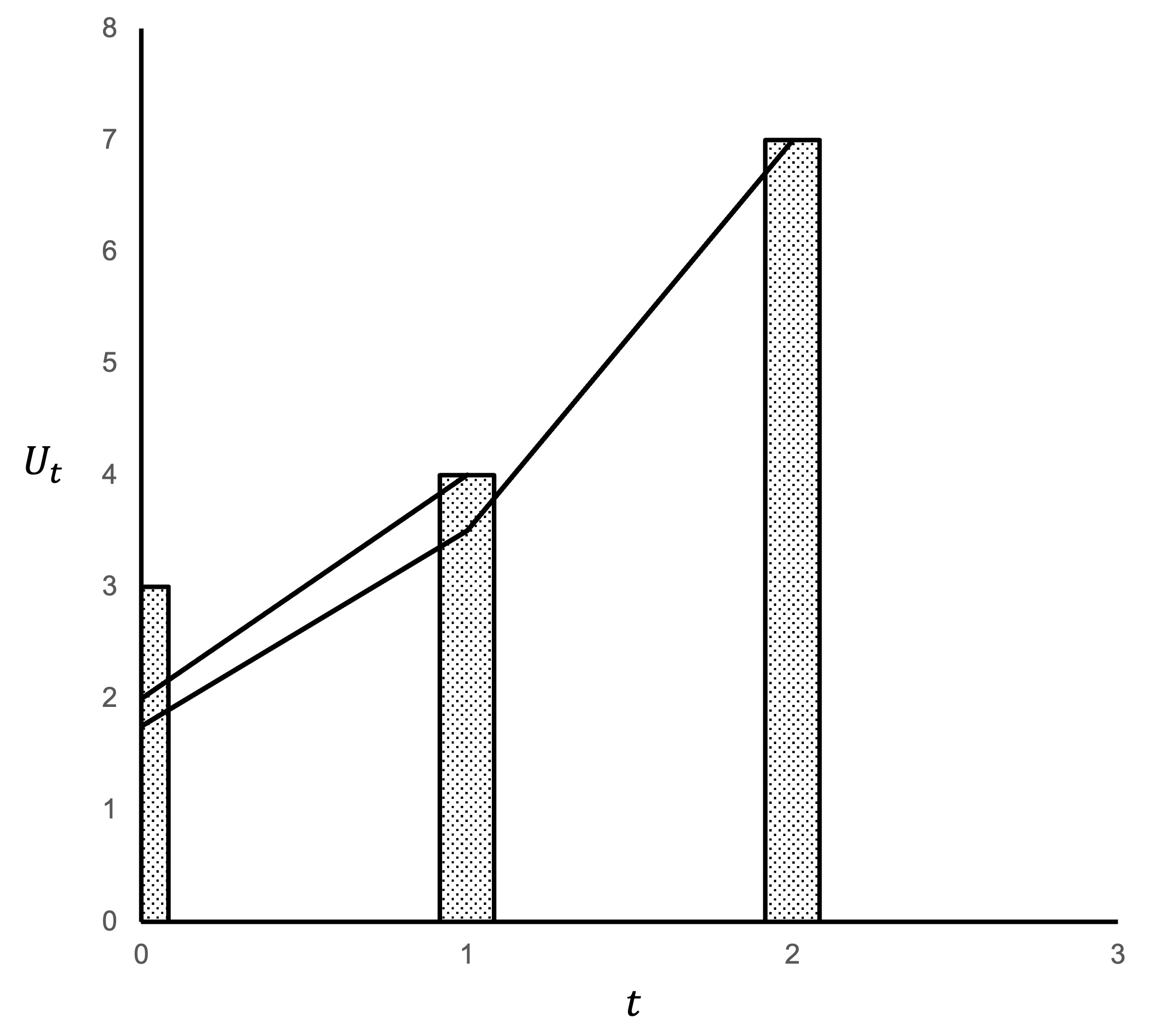

The below figure shows the each of the payoffs that Kate could receive at t=0,1,2. The lines represent the discounted utility of each option at each time.

At t=0 we can see that the $3 immediately gives higher discounter utility than both of the larger, later options.

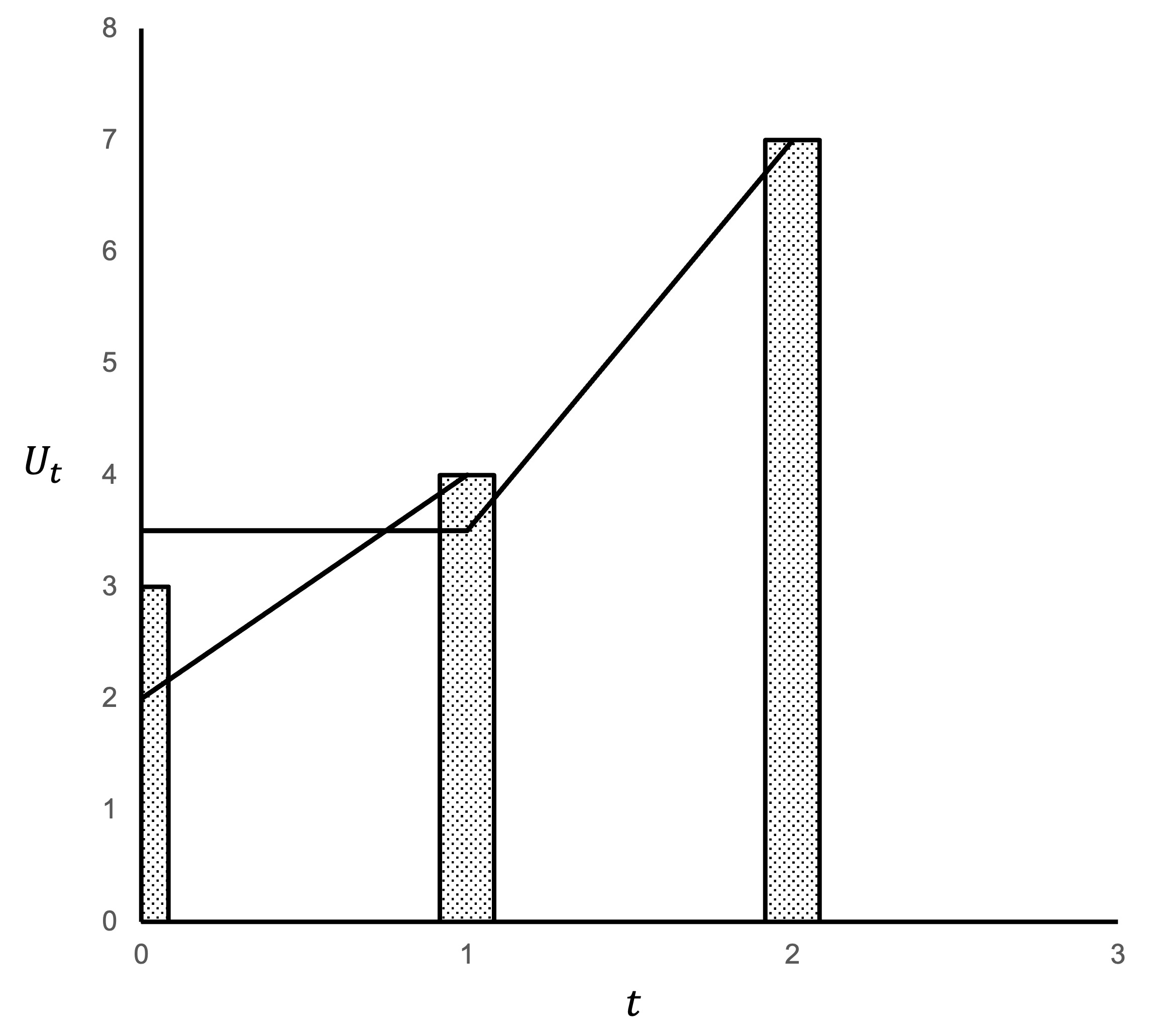

The below figure shows the each of the payoffs that Jack could receive at t=0,1,2. The lines represent the discounted utility of each option at each time.

At t=0 we can see that the $4 paid at t=1 gives higher discounter utility. We can also see that the lines represented the discounted utility at each time cross, giving the potential for a time inconsistent decision.

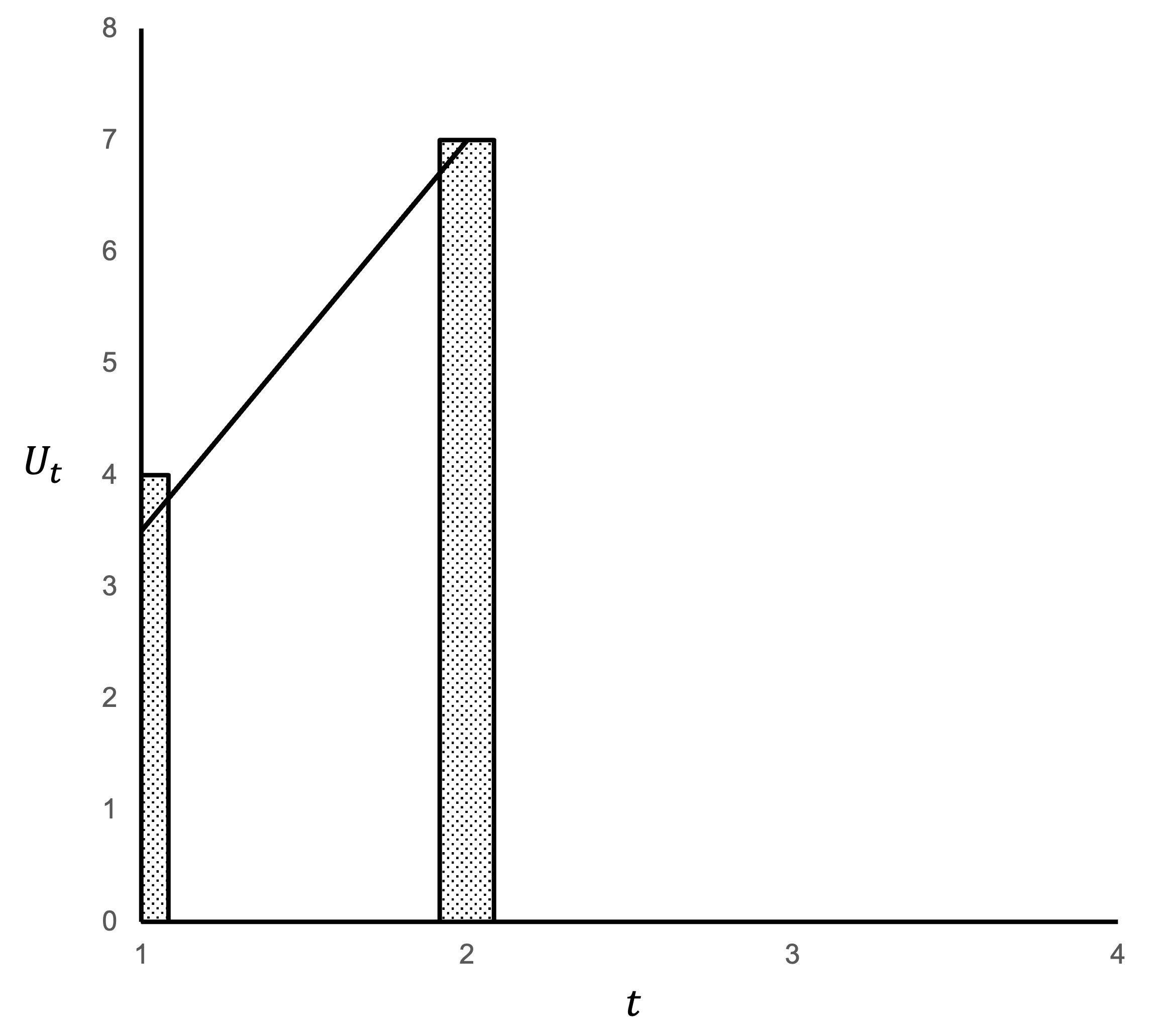

In the next figure we move forward to t=1. Jack’s preferred option changes. He now prefers the $4 immediately. It is no longer discounted by \beta.

30.4 Small reward now or large reward later?

Alfred and Blake are exponential discounters. They can choose between a small reward now or a larger reward later. Alfred discounts the future heavily (low \delta). Blake does not (\delta close to one).

a) How might Alfred and Blake’s choices be affected by their discount factor?

Each will discount the two rewards, with the size of the discount for the larger reward reflecting the size of the delay relative to the delay for the small reward.

Alfred and Blake will prefer to wait if the discounted utility of the larger reward is higher than that of the small reward.

As Alfred has a higher discount rate, Alfred is more likely than Blake to prefer the small reward as Alfred will discount the larger reward by more.

b) Catherine is a quasi-hyperbolic discounter. She can choose between the same two rewards. Before either award is available, she prefers the large reward. However, she changes her mind and chooses when the small reward at the time it becomes available.

Why did Catherine change her mind?

If Catherine prefers the large reward, this means the discounted utility of the larger reward is higher than that for the small reward. As both rewards are experienced with delay, the small and large reward are discounted by the short-term discount factor, plus the exponential discount factor proportional to the delay.

When the small reward becomes available, Catherine no longer applies any discount to the small reward. The exponential discount factor applied to the larger reward also decreases for the time that has passed. Despite the size of the exponential discount being applied to each reward decreasing by the same amount, the removal of the short-term discount factor from the small reward must have been of sufficient that it now has the larger expected utility.

30.5 Credit score

A credit score is a score developed by credit agencies and lenders as a measure of how risky a borrower is. The score is derived using data on past behaviour. A person with a higher credit score is considered more likely to repay a loan on time.

Researchers found a correlation between people’s discount factors, \beta and \delta, and their credit score.

What would this correlation be? Explain why you might see this relationship.

You would expect to see a positive correlation between the credit score and the discount factors.

\beta relates to present-bias, which results in greater weight being given to any costs or benefits today relative to costs and benefits experienced with delay.

\delta relates to impatience, with each successive period of delay being subject to a discount relative to the previous.

Both discount factors could affect the credit score.

To the extent the future is discounted due to either discount rate, this makes borrowing more attractive provided the interest costs are not too high.

If either discount factor were low enough, an agent might be willing to borrow more than they could feasibly pay off in the future (or at extortionate interest rates). The benefits of consumption today might exceed the costs of failure to repay, with those costs sufficiently discounted that them agent is willing to incur them. An agent with low \beta might be particularly vulnerable to this as an impulsive purchase today might be attractive even though the debt (e.g. credit card) might be payable soon. Failure to pay would hurt their credit score.

Unintended payment problems are more likely to be caused by low \beta.

If someone with low \delta borrowed money with the intention to pay it off in the future, they would stick to that plan. They are time consistent.

Someone with low \beta may borrow with the intention to pay it off. However, when the day of payment arrives, they may change their mind and prefer not to incur the immediate cost of payment as that exceeds the discounted costs in the future (such as penalty interest and a low credit score). This would also hurt their credit score.

30.6 Time inconsistent preferences

Recall the question in Section 30.3.

We found that at t=0 Jack planned to wait until tonight (t=2) for the $7, but in the afternoon (t=1) he changed his mind and took the $4 that was available immediately.

Jack’s friend Allan is a sophisticated quasi-hyperbolic discounter with \beta=\frac{1}{2} and \delta=1.

Does your answer change for Allan? Why?

The behaviour of Jack that we observed in Tutorial 5 was that of a naive hyperbolic discounter. In each period he calculated his preferred option and acted as though he would stick to that decision in the future. He did not anticipate changing his mind at t=1.

Allan considers the choice by using backward induction from the final period.

If Allan waits until tonight, he takes the $7 with certainty.

Now considering his choice at t=1.

\begin{align*} U_1(\$4\text{ at }t=1)&=4 \\[6pt] U_1(\$7\text{ at }t=2)&=\beta\delta\times 7 \\[6pt] &=3.5 \end{align*}At t=1 Allan can see that he will cave in take the $4.

Allan now considers t=0 with the knowledge he will take the $4 at t=1. He knows that he will not make it to the $7 at t=2, so he removes it from his choice set.

\begin{align*} U_0(\$3\text{ at }t=0)&=3 \\[6pt] U_0(\$4\text{ at }t=1)&=\beta\delta\times 4 \\[6pt] &=2 \end{align*}At t=0 Allan chooses the $3. His sophistication leads him to preproperate. He takes a lower amount earlier than the naive Jack.

30.7 Eating cake

Kelvin and Linda both like chocolate cake. There are two periods in which they can eat cake, t=1,2. They receive an immediate benefit of 12 for eating cake at t=1 and 6 for eating cake at t=2

At t=3 they incur the costs of their diet and pay a cost of 8. The total cost depends on how much cake they eat.

Kelvin and Linda have preferences of \beta=0.5 and \delta=1.

To illustrate, if Kelvin or Linda eat at t=1 they receive a benefit of 12 at t=1 and a cost of 8 at t=3. If Kelvin or Linda eat at both at t=1 and at t=2, they receive a benefit of 12 at t=1 and 6 at t=2 and a cost of 16 at t=3.

Kelvin is naive, Linda is sophisticated.

a) When will Kelvin eat?

We can calculate utility of eating in each round separately as the utilities are additive.

At t=0:

\begin{align*} U_0(\text{eat at }t=1)&=\beta\delta\times 12-\beta\delta^3\times 8 \\ &=0.5\times 1\times 12-0.5\times 1^3 \times 8 \\ &=2 \\ \\ U_0(\text{eat at } t=2)&=\beta\delta^2\times 6-\beta\delta^3\times 8 \\ &=0.5\times 1^2\times 6-0.5\times 1^3 \times 8 \\ &=-1 \end{align*}Kelvin plans to eat at t=1 but not t=2.

At t=1:

\begin{align*} U_1(\text{eat at } t=1)&=12-\beta\delta^2\times 8 \\ &=12-0.5\times 1^2 \times 8 \\ &=8 \\ \\ U_1(\text{eat at } t=2)&=\beta\delta\times 6-\beta\delta^2\times 8 \\ &=0.5\times 1\times 6-0.5\times 1 \times 8 \\ &=-1 \end{align*}Kelvin eats at t=1 but does not plan to eat at t=2.

At t=2:

\begin{align*} U_2(\text{eat at } t=2)&=6-\beta\delta^2\times 8 \\ &=6-0.5\times 1^2 \times 8 \\ &=2 \end{align*}Kelvin eats at t=2.

Kelvin, being naive, thinks he will stick to his initial plan of eating at t=1 but not at t=2, but ends up eating in both periods.

b) When will Linda eat?

Linda is sophisticated and solves their problem backward.

There is no decision to make at t=3. She simply incurs the cost of their past behaviour.

At t=2:

\begin{align*} U_2(\text{eat at } t=2)&=6-\beta\delta^2\times 8 \\ &=6-0.5\times 1^2 \times 8 \\ &=2 \end{align*}Linda anticipates that she will eat at t=2.

Linda knows she will eat at t=2, so she don’t need to reconsider her plan for then at t=1.

At t=1:

\begin{align*} U_1(\text{eat at } t=1)&=12-\beta\delta^2\times 8 \\ &=12-0.5\times 1^2 \times 8 \\ &=8 \end{align*}Linda also anticipates that she will eat at t=1.

At t=0, Linda can now see that she will eat at t=1 and t=2 no matter what she decides now. She simply accepts her future course of action.

c) Assume that Kelvin and Linda can pay price p at t=0 for a binding commitment device that prevents them from eating more than they initially plan. Assuming costs and benefits are measured in dollars, what is the maximum price p that Linda would pay to use the commitment device?

From the perspective of period t=0 all costs and benefits are discounted. At t=0:

\begin{align*} U_0(\text{eat at } t=1)&=\beta\delta\times 12-\beta\delta^3\times 8 \\ &=0.5\times 1\times 12-0.5\times 1^3 \times 8 \\ &=2 \\ \\ U_0(\text{eat at } t=2)&=\beta\delta^2\times 12-\beta\delta^3\times 8 \\ &=0.5\times 1^2\times 6-0.5\times 1^3 \times 8 \\ &=-1 \end{align*}From the perspective of t=0, eating at t=2 has negative discounted utility. As a result, if a commitment device available, Linda would use it to commit to not eating at t=2. The commitment device would prevent a loss of 1. Therefore, Linda would pay up to p=\$1.

d) What happens to Kelvin, a naive agent, in the presence of the commitment device?

Being naive, Kelvin does not perceive the necessity of using a commitment device as he trusts he will comply with his plans.

30.8 Completing an assignment

Your assignment is due today at t=0.

You can complete the assignment within a day, but on that day you will incur a utility cost of 10.

For every day you submit late, you lose one mark. You experience a utility cost of 1 for every mark lost on the day it is lost. If handed in more than 6 days late, you will fail and experience utility cost of 1000. (In other words, if you haven’t yet submitted, you will definitely submit at t=6).

This leaves you with a decision to hand in at t = 0, t = 1, t = 2, ... , t = 5, or t=6.

For instance:

- If you submit today, at t=0, you experience utility cost of 10.

- If you submit tomorrow, at t=1, you will experience utility cost of 10 plus a utility cost of 1 for the mark lost on that day.

- If you submit at t=2, you will experience a utility cost of 1 at t=1 for the mark lost, a utility cost of 1 at t=2 for another mark lost, and a utility cost of 10 for completing the assignment.

- If you submit at t=6, you will experience a utility cost of 1 on each day from t=1 to t=6 for the marks lost, plus a utility cost of 10 at t=6 for completing the assignment.

You are a hyperbolic discounter with \beta=0.75 and \delta=1.

a) When do you finish if you are naive?

At t=0 you have 7 possible plans to consider: finishing your assignment at t=0 through to t=6. You compare the discounted utilities from the various plans as follows.

At t=0:

- Finish today (t=0): -10

- Finish tomorrow (t=1): 0.75(-10-1)=-8.50

- Finish at t=2: 0.75(-10-2)=-9.25

- Finish at t=3: 0.75(-10-3)=-10

- …

- Finish at t=6: 0.75(-10-6)=-12

At t=0, you plan to finish at t=1 as that yields the highest discounted utility. You put off finishing the assignment until tomorrow.

At t=1 you then reconsider your decision. The penalty received at t=1 is now sunk and won’t affect the decision:

- Finish today (t=1): -10=-10

- Finish tomorrow (t=2): 0.75(-10-1)=-8.25

- Finish at t=3: 0.75(-10-2)=-9

- …

- Finish at t=6: 0.75(-10-5)=-11.25

At t=1, you change your plan and now intend to finish at t=2, which yields the highest discounted utility.

This pattern continues day after day, always intending to complete tomorrow, until t=6, with an ultimate outcome of -10 utility cost on that day, plus -1 utility cost each day for the last 6 days.

- Finish at t=5: -10

- Finish at t=6: 0.75(-10-1)=-8.25

b) When do you finish if you are sophisticated?

If you are sophisticated, you will start at the end and work backwards.

At t=6, you know that if you haven’t finished the assignment you must, with -10 utility.

At t=5, you choose between:

- Finish at t=5: -10

- Finish at t=6: 0.75(-10-1)=-8.25

You do not plan to do the assignment at t=5 and you remove t=5 from your plans.

At t=4, you choose between:

- Finish at t=4: -10

- Finish at t=6: 0.75(-10-2)=-9

You do not plan to do the assignment at t=4 and you remove t=4 from your plans.

At t=3, you choose between:

- Finish at t=3: -10

- Finish at t=6: 0.75(-10-3)=-9.75

You do not plan to do the assignment at t=3 and you remove t=3 from your plans.

At t=2, you choose between:

- Finish at t=2: -10

- Finish at t=6: 0.75(-10-4)=-10.5

Utility is higher completing the assignment earlier. You plan to do the assignment at t=2 and you remove t=6 from your plans.

At t=1, you choose between:

- Finish at t=1: -10

- Finish at t=2: 0.75(-10-1)=-8.25

You plan to do the assignment at t=2 and you remove t=1 from your plans.

At t=0, you choose between:

- Finish at t=0: -10

- Finish at t=2: 0.75(-10-2)=-9

You will not change your intentions further and will complete the assignment at t=2.

30.9 Saving for retirement

Citizens of Perthia have the choice between the following options:

- Saving for retirement at t=1 (u_1=0) and having a comfortable retirement at t=2 (u_2=20)

- Spending at t=1 (u_1=10) and having a difficult retirement at t=2 (u_2=0).

a) Ellie is an exponential discounter with \delta=3/4. What does Ellie choose at t=0 and t=1? Why?

Ellie intends to save in both periods and does so. Ellie is time consistent. Knowing that Ellie is an exponential discounter, we did not need to calculate her decision at both t=0 and t=1. As exponential discounters are time consistent, we could have simply determined her decision for one period and known that would also be her decision at other times.

b) Freddie is a naive quasi-hyperbolic discounter with \beta=1/4 and \delta=1. What does Freddie choose at t=0 and t=1? Why?

At t=0 Freddie plans to save.

\begin{align*} U_1(save)&=u_1+\beta\delta u_2 \\ &=0+\frac{1}{4}\times 1\times 20 \\ &=5 \\ \\ U_1(spend)&=u_1+\beta\delta u_2 \\ &=10+0 \\ &=10 \end{align*}At t=1 Freddie chooses to spend Freddie has changed his mind. He is time inconsistent. At t=0 both saving and spending are subject to the short-term discount factor \beta, with the relative discount between saving and spending being only \delta. However, at t=1 the benefit of spending is available immediately and no longer discounted by \beta.

c) Grant is a sophisticated quasi-hyperbolic discounter with \beta=1/4 and \delta=1. What does Grant do? Why?

Grant works through his options using backward induction.

At t=2 Grant has no decision to make.

At t=1:

\begin{align*} U_1(save)&=u_1+\beta\delta u_2 \\ &=0+\frac{1}{4}\times 1\times 20 \\ &=5 \\ \\ U_1(spend)&=u_1+\beta\delta u_2 \\ &=10+0\\ &=10 \end{align*}At t=1 Grant will spend. (This is the same calculation we made for Freddie at t=1.)

As Grant knows he will spend at t=1, that is the only feasible option available at t=0. Grant will choose to spend.

Ultimately, Grant takes the same action as Freddie. However, he can see his future decisions and is aware of that coming failure to stick with what would be his preferences at t=0.

d) Grant is offered the opportunity to bind himself to a course of action at t=0 at the cost of 1 point of utility at t=2. What does Grant do?

In the presence of the commitment device, Grant now has two feasible options to consider at t=0.

\begin{align*} U_0(commit)&=\beta\delta u_1+\beta\delta^2 u_2 \\ &=0+\frac{1}{4}\times (1)^2\times (20-1) \\ &=4.75 \\ \\ U_0(spend)&=\beta\delta u_1+\beta\delta^2 u_2 \\ &=\frac{1}{4}\times 1\times 10+0 \\ &=2.5 \\ \end{align*}Grant now chooses to commit at a price of one unit of utility at t=2.

30.10 Buy-now pay-later

Buy-now pay-later works as follows: a person purchases an item with an initial payment of one-quarter of the purchase price. They get access to the purchased item immediately. They then pay three equal instalments each fortnight until they have paid for the purchase in full. If they fail to make a payment on time, they are required to pay a fee of $10 and are barred from using the buy-now pay-later facility in the future.

Vernon used a buy-now pay-later provider to purchase a new jacket for $200. He paid $50 on the day of the purchase and is now required to pay the next $50 instalment in two weeks. That is, Vernon’s schedule of costs and benefits is:

- Purchase date: Gains jacket and pays $50

- In two weeks: Pays $50

- In four weeks: Pays $50

- In six weeks: Pays $50

At that time of the purchase Vernon intends to pay for the jacket as required by the buy-now pay-later provider in two, four and six weeks.

Two weeks after the purchase when his payment became due Vernon changed his mind and did not make the payment. He purchased a carton of beer for a party that night with the money instead. Vernon’s options and the cost and benefits of those options had not changed since the purchase date.

Is Vernon an exponential discounter or present-biased? Why? Explain why Vernon changed his mind.

As Vernon has exhibited time inconsistent behaviour, he must be present-biased. An exponential discounter would be time consistent.

A present-based person subjects costs and benefits experienced with any delay to a short-term discount factor.

When Vernon purchased the jacket, the benefit of the jacket and the cost of $50 would not have been subject to any discount. The cost of the three future payments (or the benefit of alternative uses of that money such as purchasing beer) would be subject to the short-term discount. Any fee for failing to make a payment and the loss of the buy-now pay-later facility for that failure would also be subject to that short-term discount factor.

When the next payment is due, the cost of that payment (or the benefit of the beer) is no longer subject to the short-term discount factor, whereas any fee from failing to make the payment and the loss of the facility are still subject to that short-term discount factor. As a result, cost of the payment / benefit of the beer now has relatively greater weight than the future costs, leading Vernon to change his mind.