51 Reciprocity

Reciprocity involves like-for-like behaviour. Kindness is responded to with kindness. Unkindness is responded to with unkindness.

Reciprocity might be considered to have two forms.

The first is instrumental reciprocity. Agents reciprocate behaviour due to the long-term benefits of sustained cooperation. The behaviour is motivated by the positive trade-off between long-term and short-term gains.

The second is intrinsic reciprocity. Agents reciprocate behaviour despite the absence of long-term gains.

51.1 Intentions

We can see evidence for reciprocity in how people respond to the intentions of others in the ultimatum game.

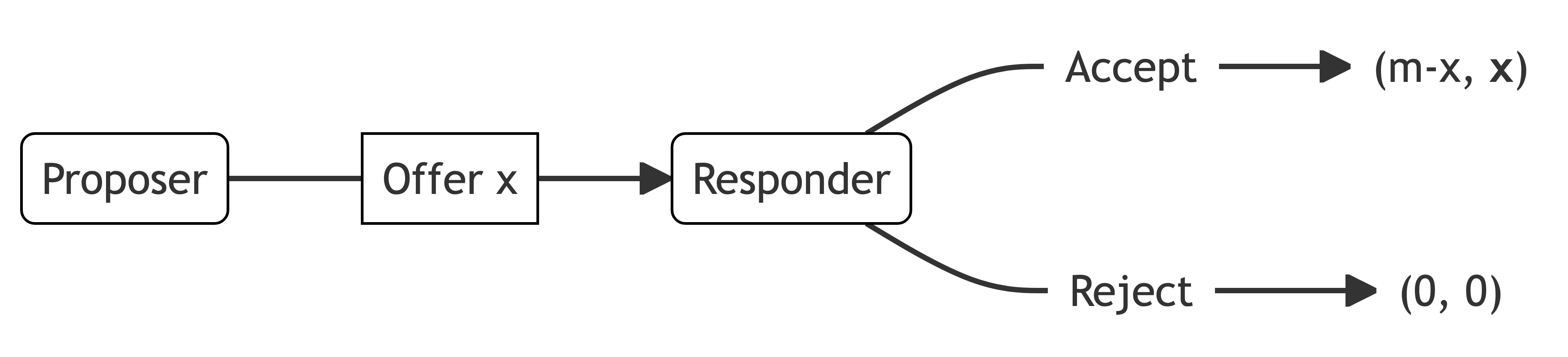

The ultimatum game involves two players: the proposer and the responder.

The proposer is given a fixed amount of money m. They then offer a portion x of the sum m to the responder.

The responder can either accept or reject the offer. They make this decision knowing the fixed amount m held by the proposer and the offer x.

If the responder accepts, the responder receives the offer x and the proposer gets the remainder m-x. If the responder rejects, both players receive nothing.

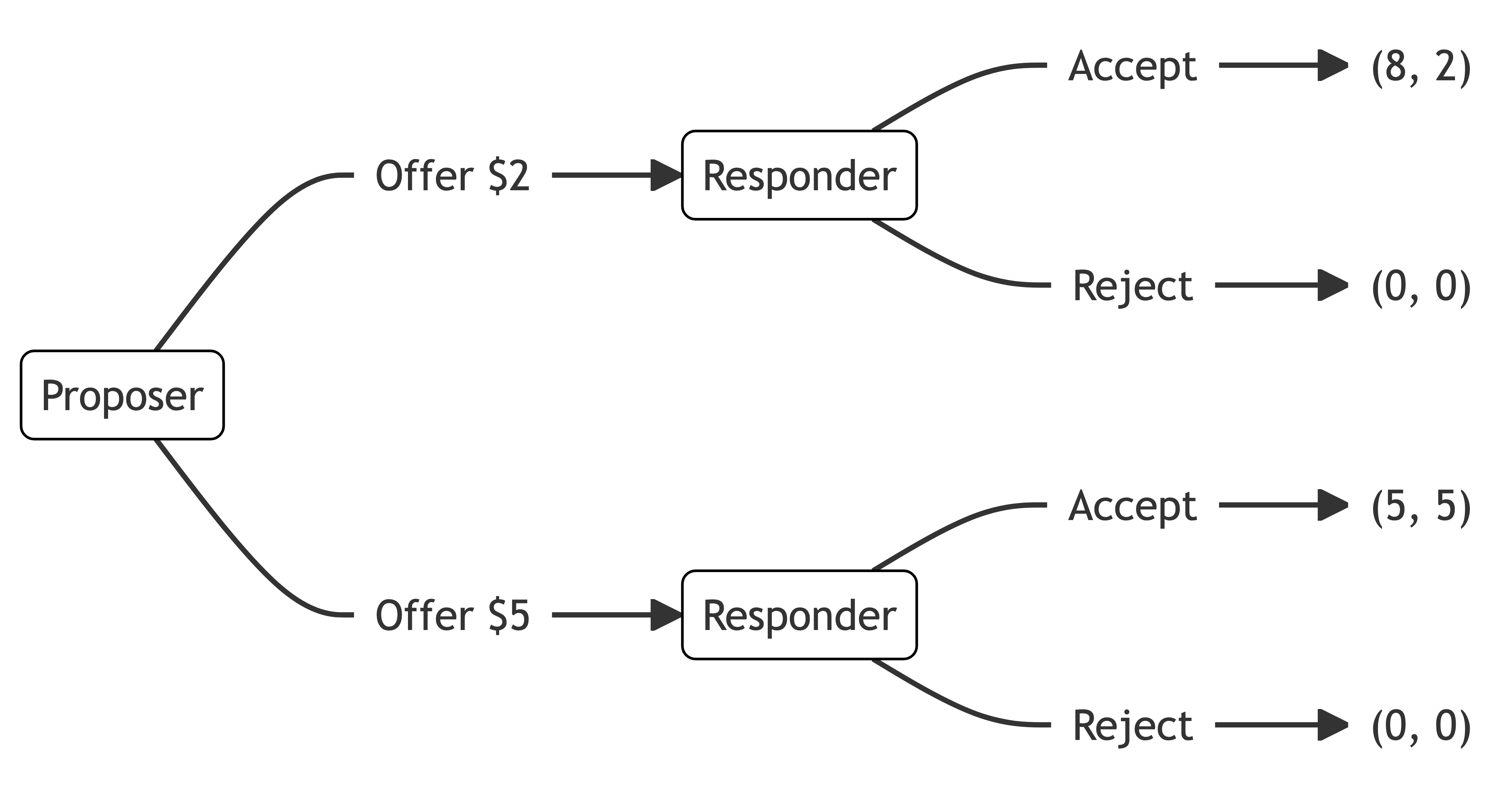

Consider this variation of the ultimatum game. In each of two scenarios, the proposer has a constrained choice of offers.

In scenario 1, the proposer has a choice between offering a split of $8 for the proposer and $2 for the responder or $5 for the proposer and $5 for the responder. Responders tend to reject offers of $2.

In scenario 2, the proposer has a choice between offering a split of $8 for the proposer and $2 for the responder or keeping the full $10 for themselves. Responders tend to accept offers of $2.

In the first scenario, responders reject offers of $2. In the second, they accept them. How can ($8, $2) be better than ($0, $0) in one scenario but not in the other?

Distributional concerns cannot explain rejection in this case. An offer of ($8, $2) leads to the same distribution in both scenarios.

Instead, responders do not base their decision on the outcome alone. They use their knowledge of the proposer’s options, consider the proposer’s intentions and reciprocate them.

A proposer who offers $2 instead of $0 is seen as having good intentions. A proposer who offers $2 instead of $5 is seen as having bad intentions.

51.2 The trust game

The trust game, which I introduced in Section 41.4.3, provides another potential example of reciprocity.

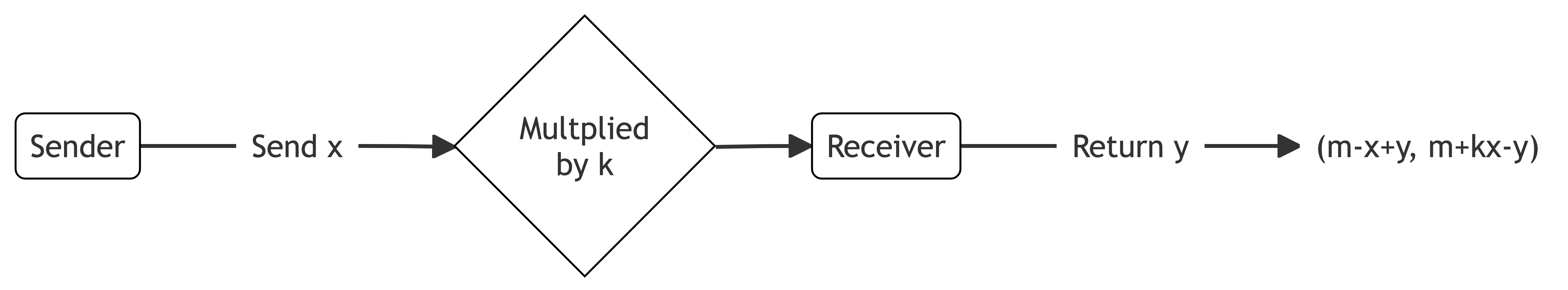

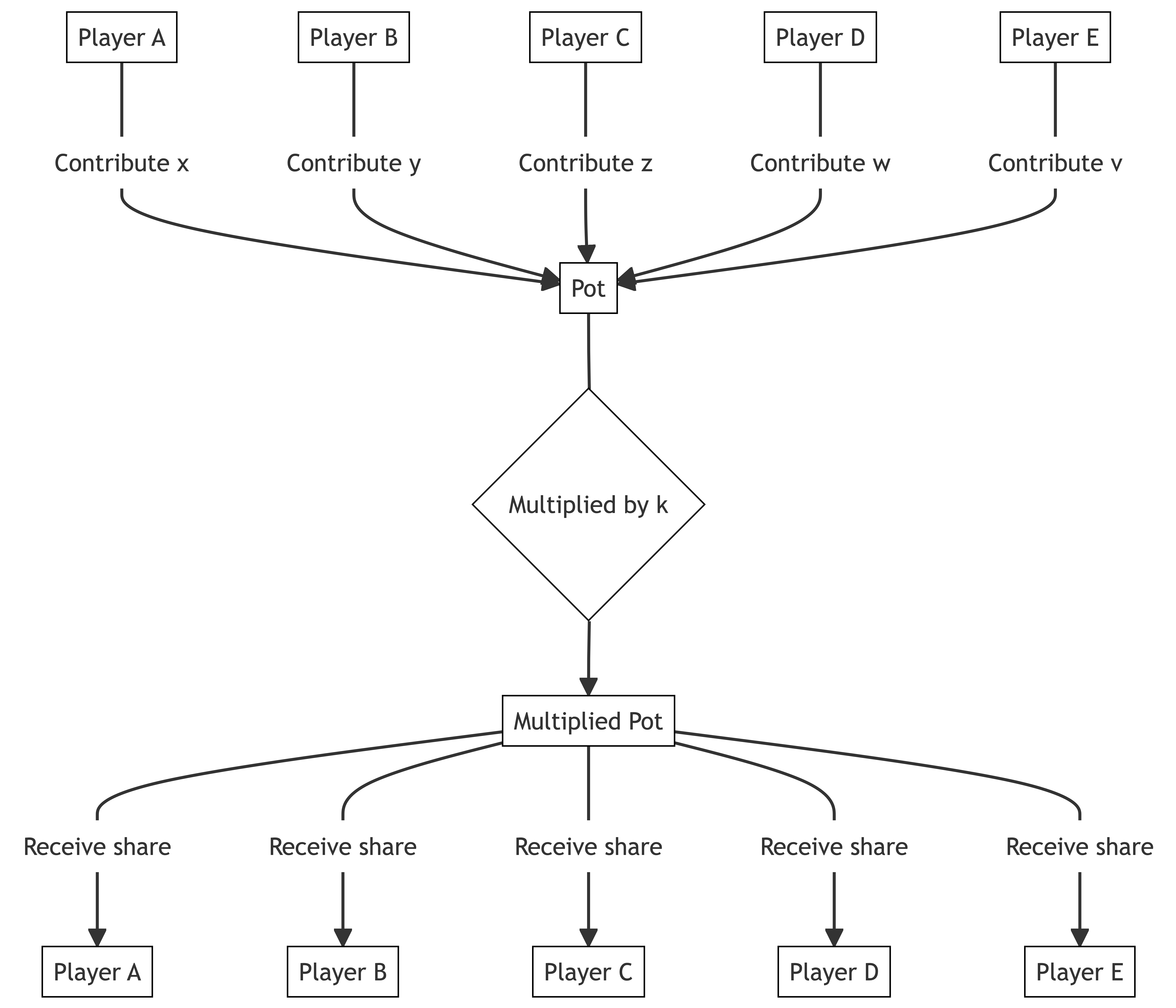

The trust game involves two players: a sender and a receiver

Both the sender and receiver are given an initial sum m.

The sender sends a share x of their m to the receiver. This amount x is often called the investment.

Before the receiver receives the investment, it is multiplied by some factor k. Therefore, the receiver receives kx.

The receiver then returns to the sender some share y of their total allocation m+kx.

The final outcome is the sender has m-x+y and the receiver has m+kx-y.

The game theoretic equilibrium is for the receiver to return nothing, so the sender sends nothing.

Contrast this with what happens in experimental settings.

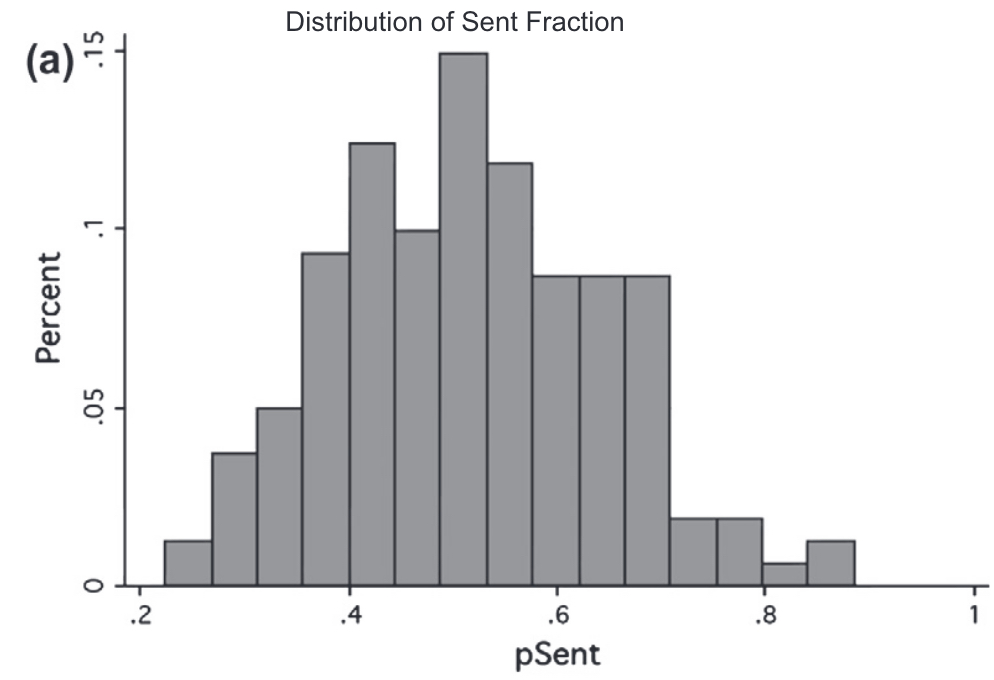

Senders tend to send a positive amount, typically around half of their endowment.

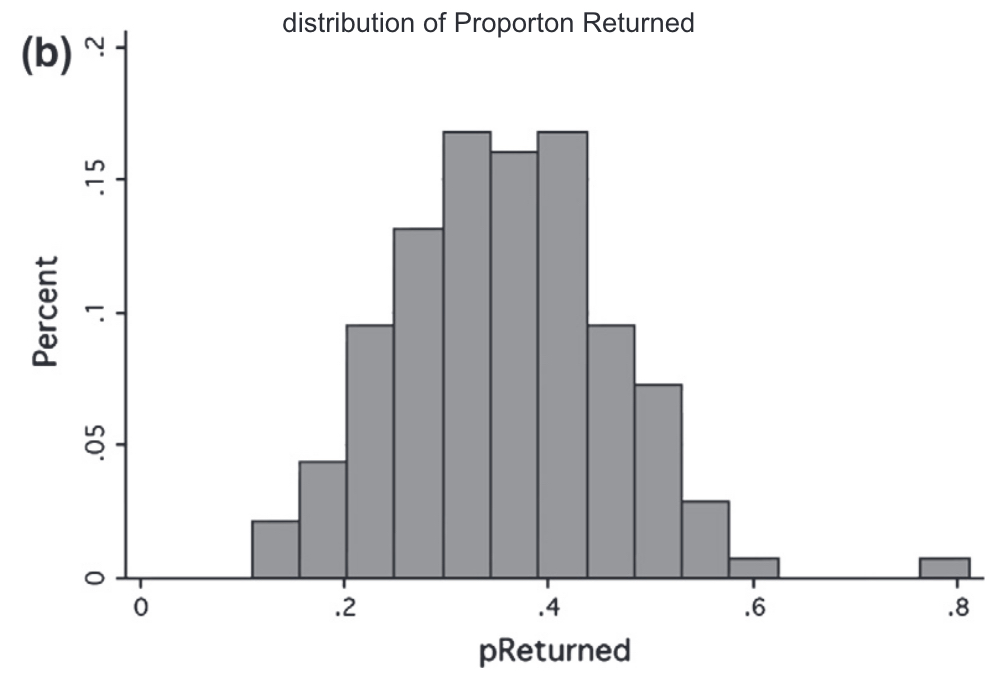

Receivers tend to send back a bit less than is sent.

These two figures from Johnson and Mislin (2011) illustrate the distribution of investments and returns in 162 replications of the trust game.

One possible explanation for this behaviour is that the receiver feels they should reciprocate the sender’s investment. They are responding to the sender’s intentions. The sender trusts that some of their investment will be repaid due to reciprocation.

The receiver’s behaviour is also consistent with altruism and inequality aversion.

51.3 The public goods game

As a final example of reciprocity, consider the public goods game.

Each of N participants is given an initial endowment.

Each participant secretly and simultaneously chooses how much of their endowment they wish to contribute to a public pot.

The money in the public pot is multiplied by some amount and split evenly between the players. Typically, the multiple applied to the pot is greater than one but less than the number of players.

In Nash equilibrium in the public goods game, nobody transfers anything to the pot. Any contributions are split between all players, so if there are more players than the multiple, which is normally the case by design, contributions result in a loss to that individual player.

This is not what we see when people play the public goods game in the lab.

In a meta-analysis, Zelmer (2003) found an average contribution of 38% of the endowment. The amount contributed increased with the marginal per capita return; that is the higher k/N.

One possible explanation is that players trust that the other players will contribute, so they desire to reciprocate the expected contributions from others.

Another explanation hinges on social norms. Where a norm of behaviour exists, people tend to follow it.