23 Exponential discounting anomalies

Summary

- Empirical investigations have revealed several anomalies inconsistent with the exponential discounting model.

- Estimates of the discount factor \delta show high variability across studies, with evidence suggesting it increases with the time horizon, contrary to the constant rate assumed in exponential discounting.

- Preference reversals have been observed in experiments, where subjects change their choices as the time to receive rewards draws closer, violating the time consistency assumption of exponential discounting.

- Real-world scenarios, such as choices between healthy and unhealthy snacks, provide further evidence of time inconsistency in decision-making, challenging the exponential discounting model’s assumptions.

23.1 Introduction

Empirical investigation of people’s choices over time has revealed several anomalies that are inconsistent with the exponential discounting model.

23.2 Estimation of \delta

The first anomaly is that estimates of the discount factor \delta are highly variable.

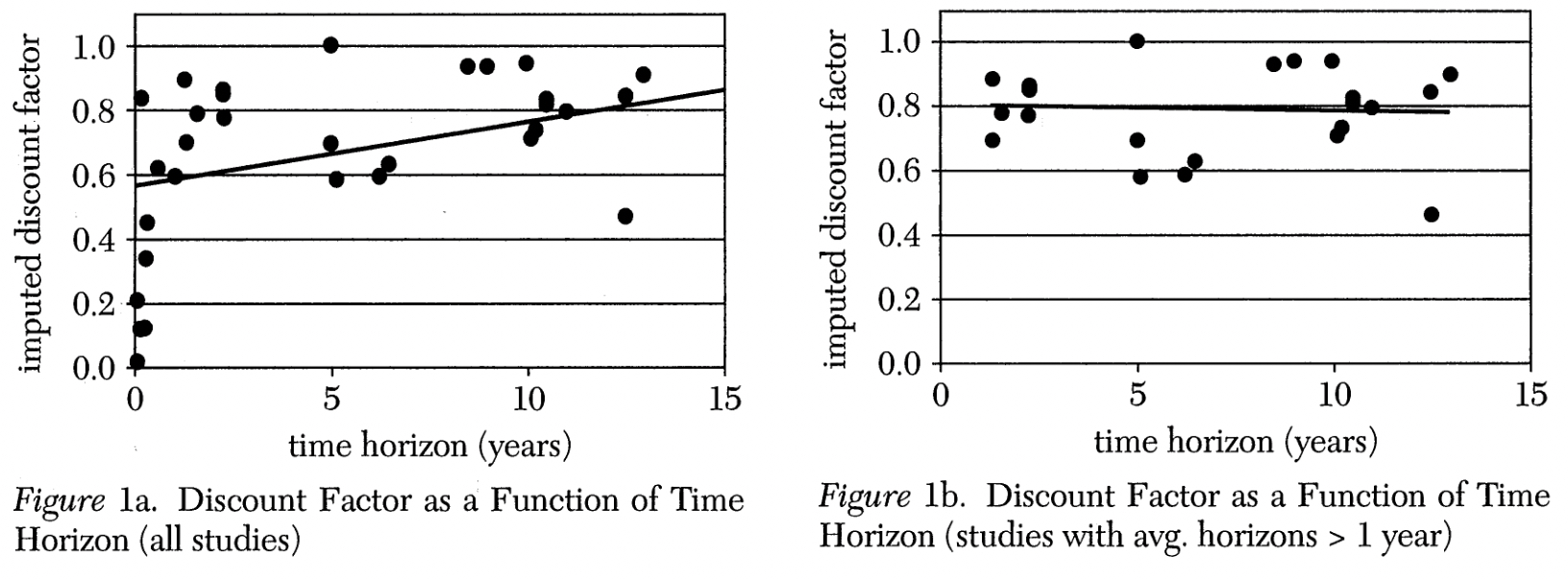

Frederick et al. (2002) plotted estimates of \delta from a set of published papers. Figure 1a shows that the estimated discount factor increases with the time horizon. If studies with horizons of one year or less are excluded, there is no relationship between the discount factor and time horizon (Figure 1b).

This suggests that the discount factor may vary with time.

Similar evidence comes from Thaler (1981). He estimated the discount rate of experimental subjects by presenting them with a choice between a prize today or a larger prize later. In each case, the subjects were asked, given the size of the prize that could be received today, how large would the future prize would need to be such that waiting would be as attractive as receiving the money now.

For example, some subjects were asked how large a future prize would need to be such that they would be happy to wait three months, one year or three years rather than receiving $15 today. The median answers were $30, $60 and $100 respectively. If you use these answers to calculate an implied discount rate, the result is 277%, 139% and 63%. It can be seen that this discount rate is decreasing with the length of delay (which matches a pattern of an increasing discount factor with the length of delay).

23.3 Preference reversal

A second anomaly relates to the consistency of choices over time. An exponential discounter is time consistent in that if they prefer one of two future payoffs, they will continue to prefer that same payoff as they get closer to the time of receipt. They do not experience what is called a preference reversal.

Green et al. (1994) offered experimental subjects choices between a smaller reward and a delayed larger reward while varying the delay. For example, they offered the choice between:

first, $20 now or $50 in three months

second, $20 in one week or $50 in three months and one week.

Across the choices offered to the experimental subjects, there was a consistent effect whereby incrementing the delay for both rewards equally would result in a switch from the small sooner reward to the latter larger reward. Adding one week to both rewards in the first choice can result in people changing their preference between the sooner and later reward.

A similar result was found in a study by Kirby and Herrnstein (1995). In that case, 34 of 36 experimental subjects reversed preference from a larger later reward to a smaller earlier reward as the delays to both decreased.

Here is one intuitive set of choices from Thaler (1981).

Choice A: Choose between one apple today and two apples tomorrow.

Choice B: Choose between one apple in one year and two apples in one year plus one day.

Some people might select one apple today in the first choice, but no-one would select one apple in one year in the second choice.

23.3.1 Healthy choices

We can also see evidence for preference reversal when choosing between a healthy and unhealthy option.

Read and Leeuwen (1998) asked 200 study participants to choose between healthy or unhealthy snacks that they would receive in one week. For example, for their snack next week, they might choose between a banana, apple, Mars bar or Snickers bar. 48% of men and 51% of women chose the healthy choice.

At the scheduled time one week later the experimenters asked the study participants to choose again. Although no reference was made to their previous choice, this effectively allowed them to change their mind. This time, only 25% of men and 11% of women chose the healthy snack. While many changed from the healthy to the unhealthy snack, almost no one changed from the unhealthy to the healthy snack.

This result is evidence of time inconsistency. The participants made different decisions depending upon when they made the decision.