43 Strategic moves and commitment

Summary

- Strategic moves are actions that change the game being played, typically from a single-stage to a two-stage game. They come in two forms: unconditional (commitments) and conditional (threats and promises).

- For commitments to be effective, they must be observable and irreversible.

- Conditional strategic moves must be credible. If carrying out a threat or promise is too costly for the player making it, the threat or promise won’t influence the other player’s actions.

- The game of “chicken” illustrates how strategic moves can change outcomes. Originally, this game has two pure-strategy Nash equilibria: (Straight, Swerve) and (Swerve, Straight). However, if one player commits to going straight (e.g., by removing their steering wheel), it changes the Nash equilibrium to favour that player.

43.1 Chicken

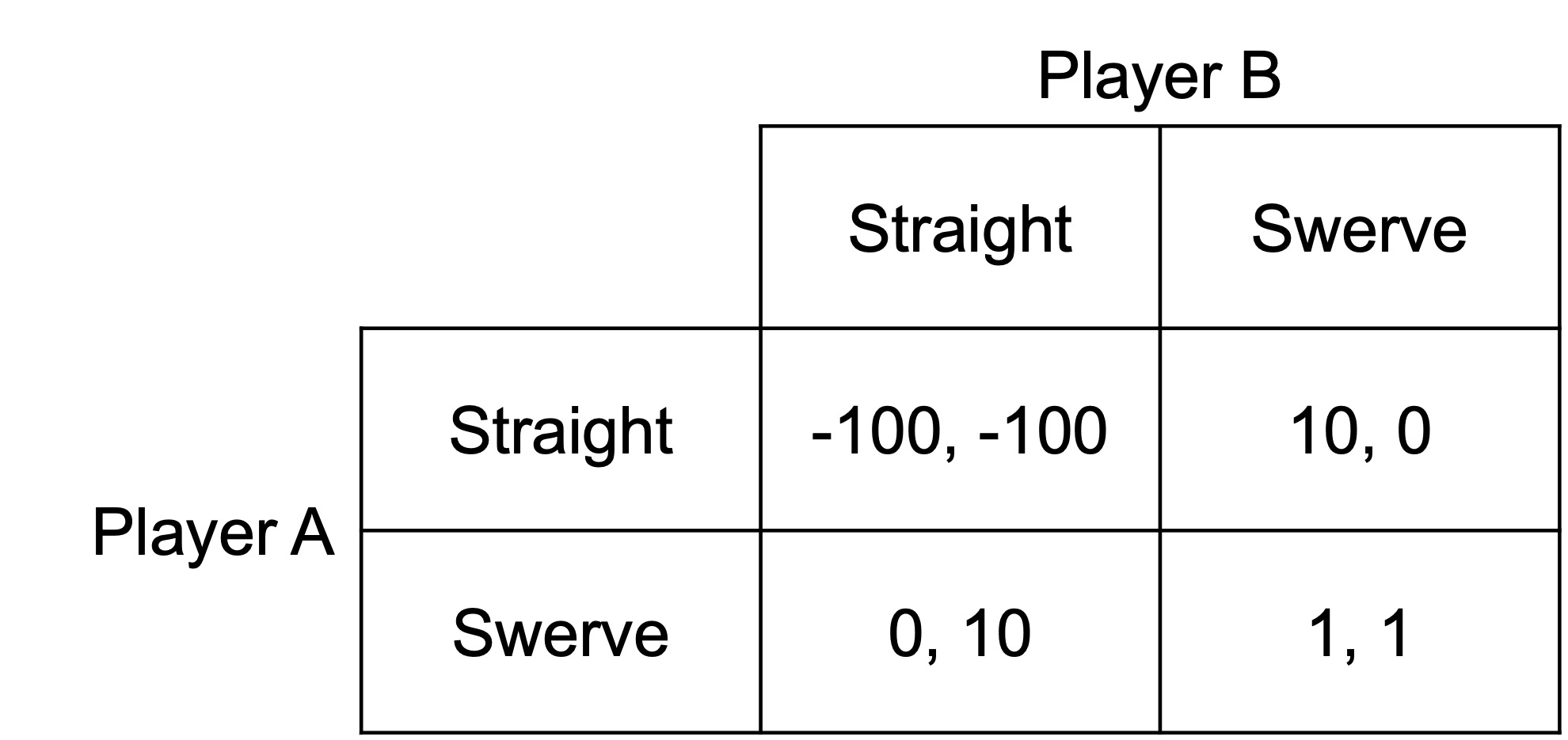

Consider the following game of chicken. Two players are driving toward each other. Whoever swerves first loses. If neither swerves, they crash and die.

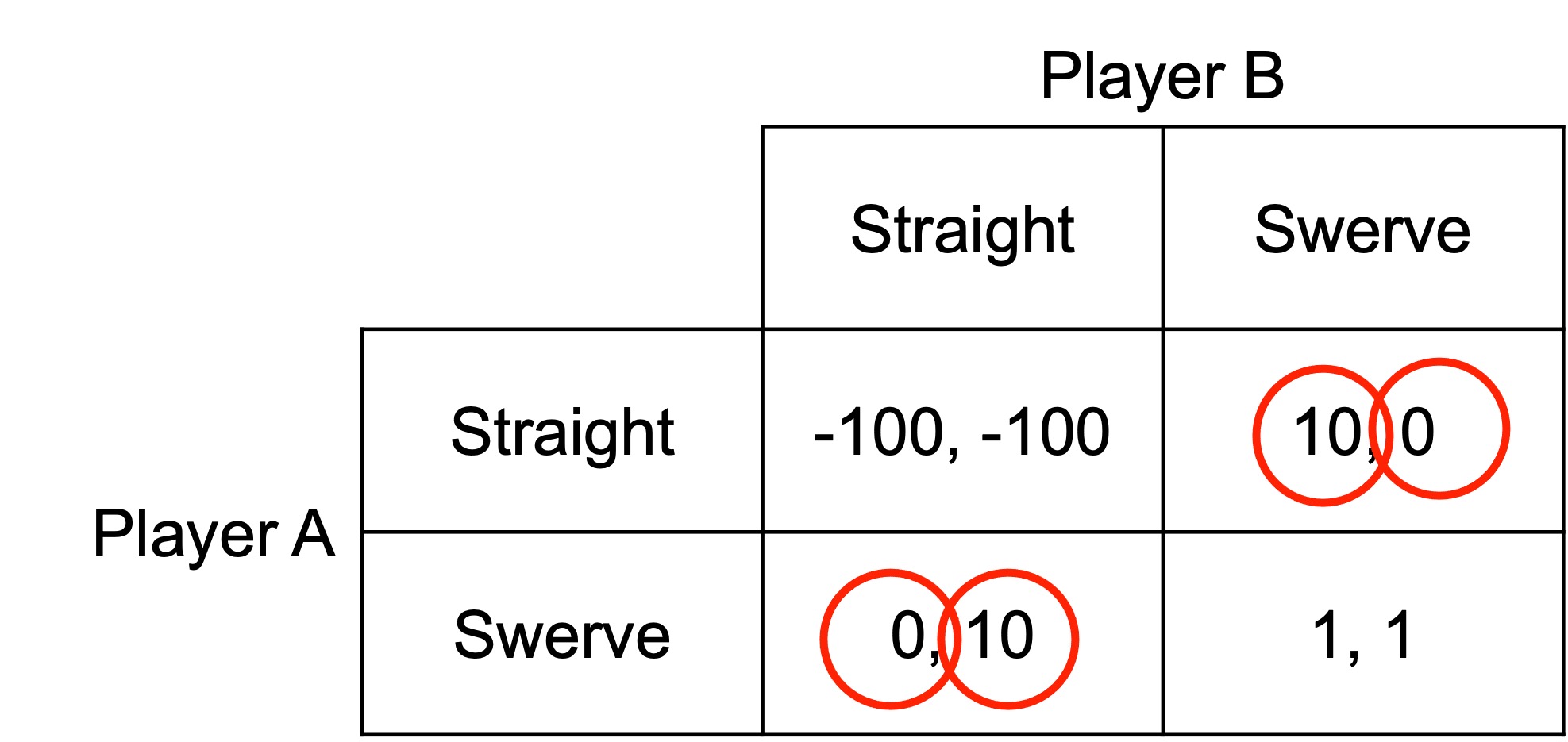

There are two pure-strategy Nash equilibria: (Straight, Swerve) and (Swerve, Straight). If the other player swerves, they want to go straight. If the other player goes straight, they want to swerve.

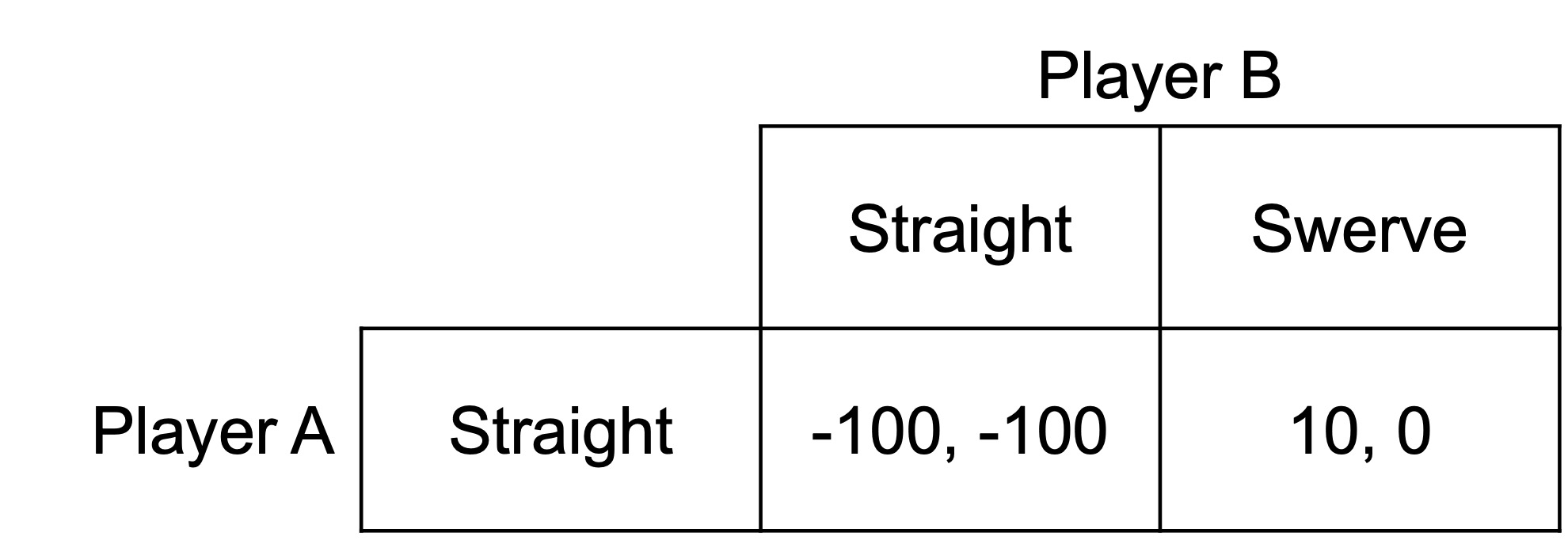

Now consider a new scenario.

As they are driving toward each other, Player A rips the steering wheel out of their car and throws it out the window. They will now drive straight no matter what Player B does.

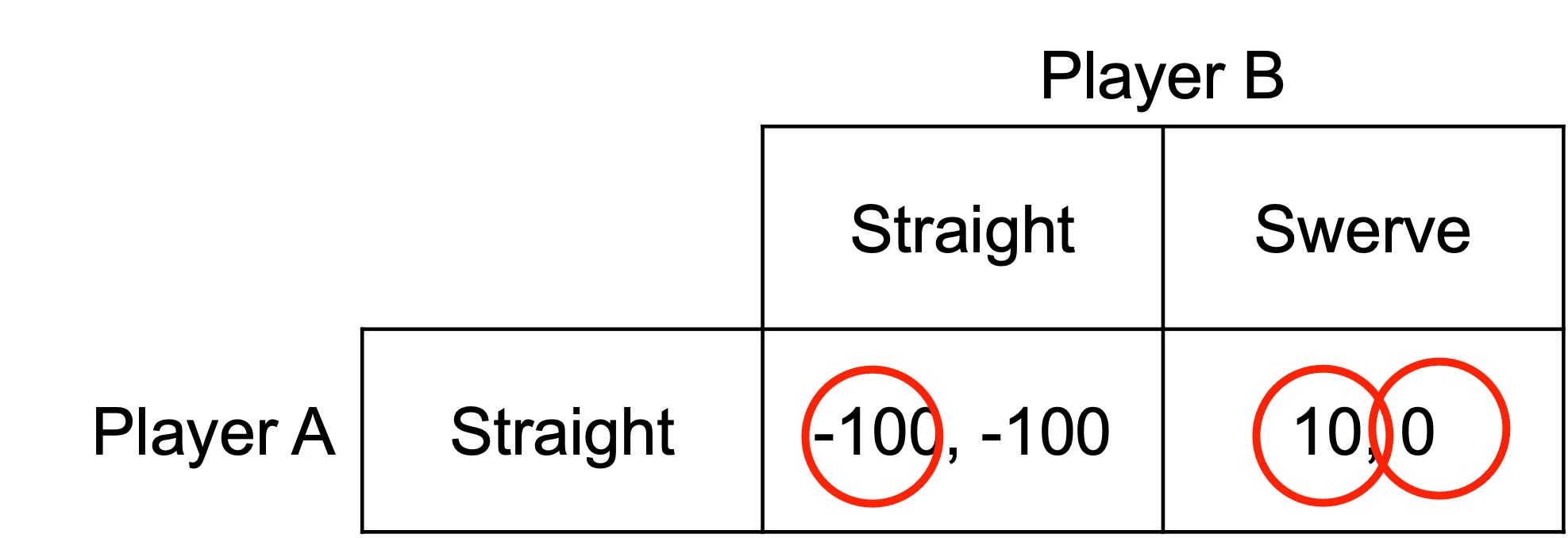

This is effectively a new game. What is the Nash equilibrium?

The Nash equilibrium is (Straight, Swerve). Player A wins the game of chicken.

43.2 Strategic moves

The option to commit to a course of action, as in this game of chicken, is an example of a strategic move.

A strategic move changes the game you are playing from a single-stage game to a two-stage game. In the first stage, you make your strategic move. In the second you play the original game.

Strategic moves come in two forms:

Unconditional strategic moves, which we call commitments

And conditional strategic moves, which we call threats and promises

43.2.1 Unconditional strategic moves

An unconditional strategic move is a commitment. For example, removing your steering wheel in chicken is a commitment.

The commitment needs to be observable and irreversible.

If your opponent cannot observe your commitment, you can claim to have made the commitment when you have not.

If your commitment is reversible, the game remains as if you had never made it.

43.2.2 Conditional strategic moves

A conditional strategic move involves specifying to your opponent how you will respond to each move.

A threat involves specifying negative consequences to the other player if they do not play as you wish. ”If you don’t clean your room, you won’t get dessert.”

A promise involves specifying positive consequences to the other player if they play as you wish. “If you clean your room, you can have dessert.”

Threats and promises only achieve their objective if they are credible. That is, they only work if the other player believes they will be carried out as stated.

Sticking to a commitment and carrying out a threat or a promise typically reduces the possible actions of the player. If the proposer loses too much from carrying out a threat or promise, they will not carry it out.

43.2.3 Example: Complaining is costly

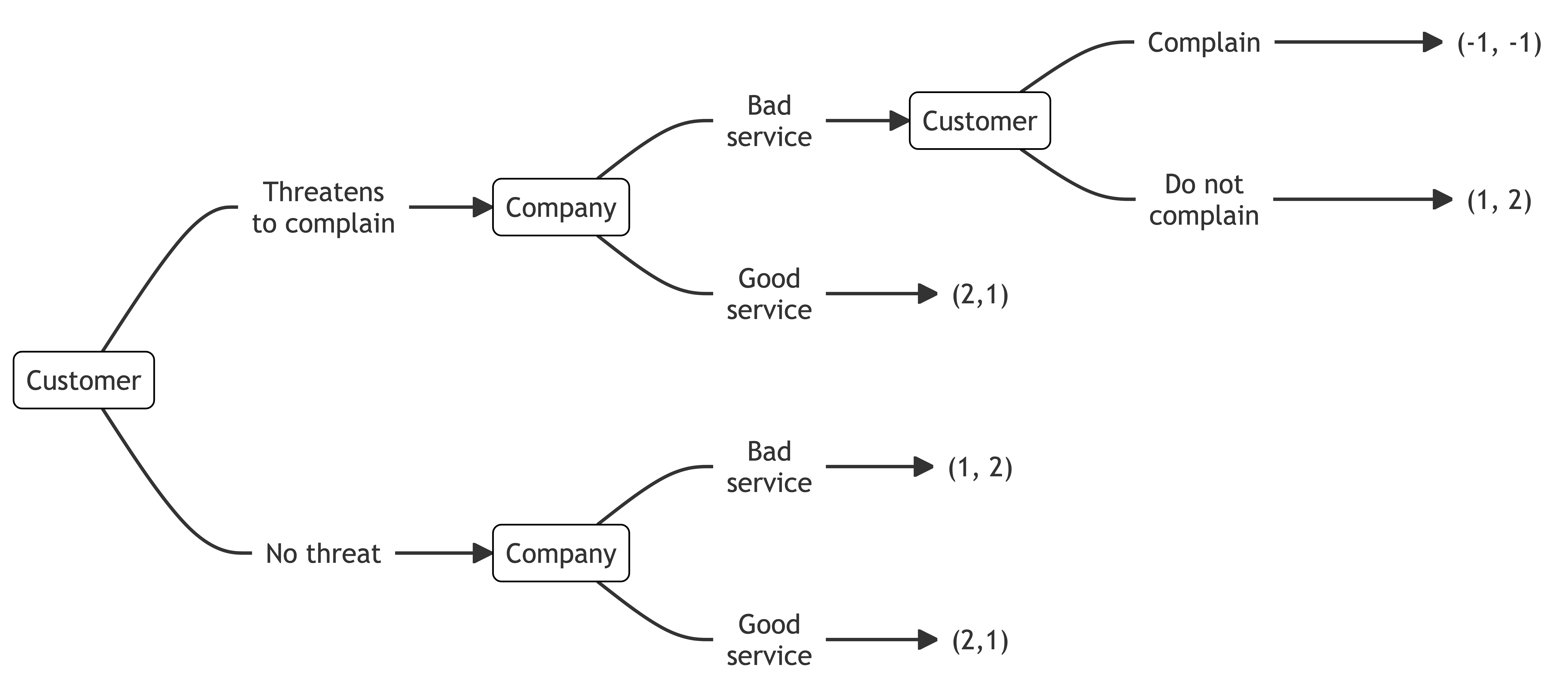

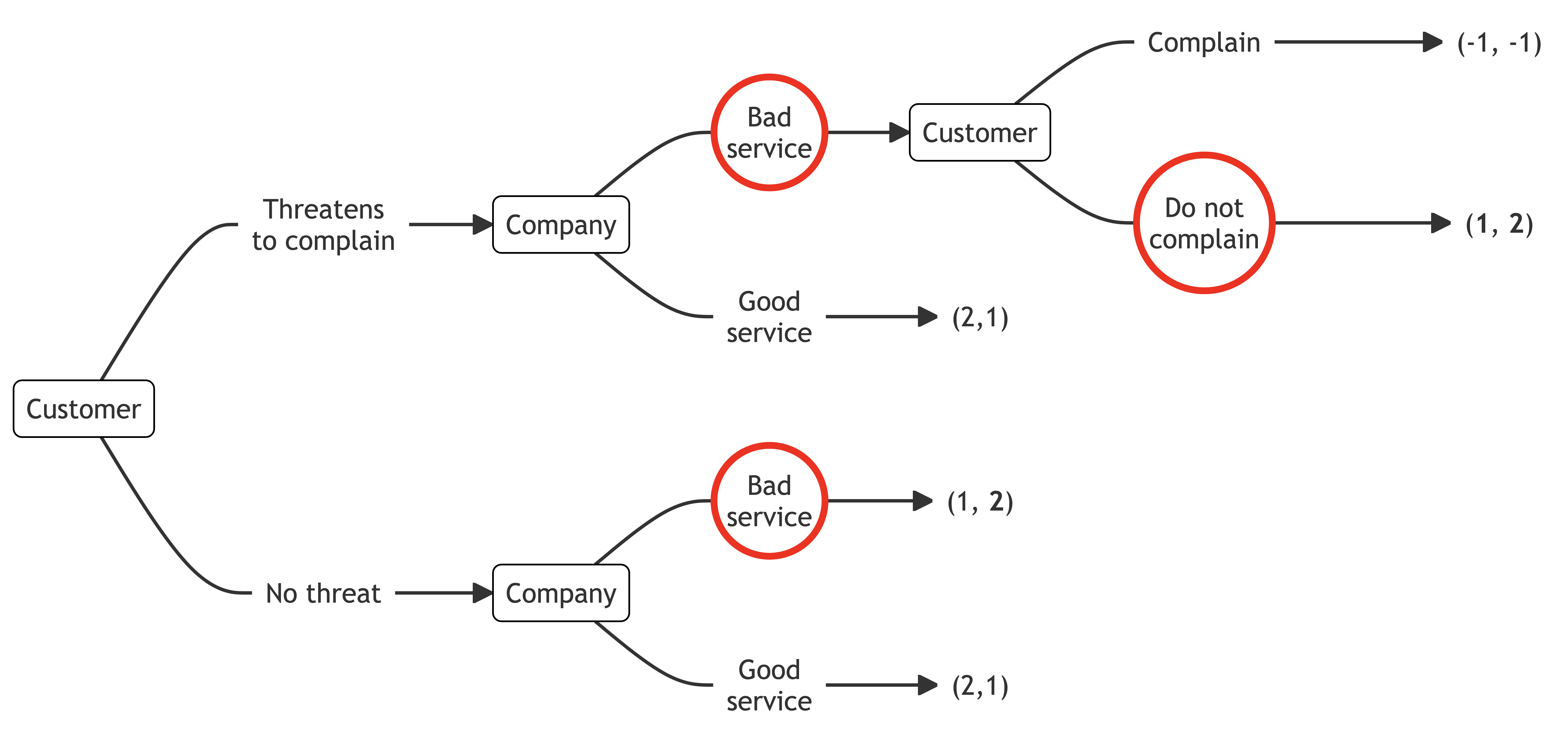

Here is an example.

You threaten to complain about poor service by a company. Complaining is costly.

We work through this problem by backward induction. At the final node for the customer, they can complain for a payoff of -1 or not complain for a payoff of 1. They will not complain.

The company, therefore, has a choice between providing good service for a payoff of 1 or bad service for a payoff of 2. They will provide bad service. The company has the same payoff for bad service regardless of the presence of the threat to complain as the threat is not credible.

For the customer’s initial choice of whether to threaten to complain, it does not matter either way. Regardless of their threat, they receive bad service.

The result is two sub-game perfect Nash equilibria: (Threatens to complain, Bad service, Does not complain) and (No threat, Bad service).