40 Simultaneous-move one-shot games

Summary

- Simultaneous-move one-shot games involve players making decisions without knowing their rival’s actions. These games are typically represented in a “normal” or “strategic” form using a matrix.

- The prisoner’s dilemma is a classic example of such a game, where two prisoners must decide whether to confess or remain silent.

- In game theory, a dominant strategy is one that yields the highest payoff regardless of the opponent’s actions. In the prisoner’s dilemma, confessing is the dominant strategy for both players.

- A Nash equilibrium occurs when each player’s strategy is the best response to the other’s strategy. In the prisoner’s dilemma, the Nash equilibrium is (Confess, Confess), despite this not being the optimal outcome for either player.

- The examples showcase different types of simultaneous-move one-shot games, demonstrating concepts such as multiple equilibria, coordination problems, and the tension between individual and collective outcomes.

- The driving game demonstrates a coordination game with two Nash equilibria: (Left, Left) and (Right, Right).

- Matching pennies is a zero-sum game with no pure-strategy Nash equilibria.

- The stag hunt game shows a coordination game with two Nash equilibria: (Stag, Stag) and (Hare, Hare), highlighting the tension between cooperation and individual safety.

- The public goods game illustrates the conflict between individual and collective interests, with the Nash equilibrium being no contribution, despite full contribution being Pareto optimal.

40.1 Introduction

In a simultaneous-move one-shot game, you make decisions without knowing the action of your rival. This can be interpreted as either players making decisions at the same time or players making decisions before knowing the decisions of their rivals.

40.2 The normal form

We usually write simultaneous move one-shot games in the “strategic” or “normal” form. In this form, all of the monetary or non-monetary outcomes are represented in a matrix.

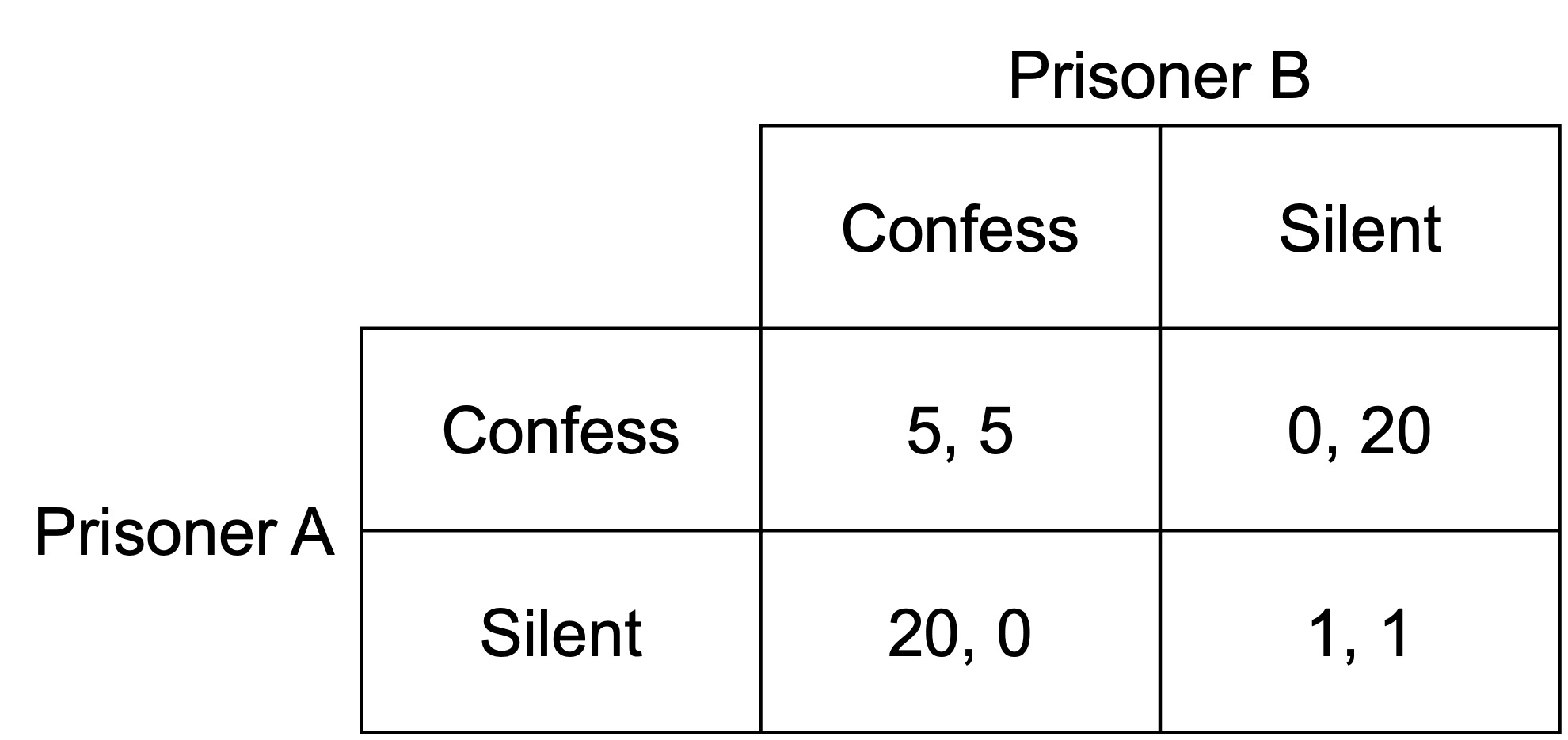

I will now illustrate the normal form of the game with a game called the prisoner’s dilemma.

40.2.1 The prisoner’s dilemma

The prisoner’s dilemma is a classic simultaneous-move one-shot game. A pair of criminals have been captured following a crime. The police have sufficient evidence to convict them of a minor crime (e.g. trespass), but insufficient evidence to convict them of the major crime that has occurred (e.g. theft of the crown jewels).

The police place each prisoner in a separate cell where they cannot communicate with each other. The police then offer both prisoners a deal: confess and they will let them go free despite the minor crime, but they will then have the evidence required to give their criminal partner a massive sentence for the serious crime.

If neither confesses, the police will have insufficient evidence to get a conviction for the major crime, so they will both receive a short sentence for the minor crime. If both confess, they will both get a longer sentence, but with some reduction in sentence relative to if they didn’t confess.

The normal form of the game is as follows:

Prisoners A and B have two actions available: to confess and to stay silent. The numbers in the matrix represent the payoffs from each combination of actions, in this case, the number of years they will serve in prison. A higher number is therefore a worse outcome. The left number in each cell of the matrix represents the payoff to the row player, Prisoner A. The number on the right of each matrix cell is the payoff to the column player, Prisoner B.

For example, if both Prisoner A and Prisoner B choose to confess, they each receive a prison sentence of five years. If Prisoner A confesses and Prisoner B remains silent, Prisoner A gets off without a prison sentence, whereas Prisoner B gets twenty years.

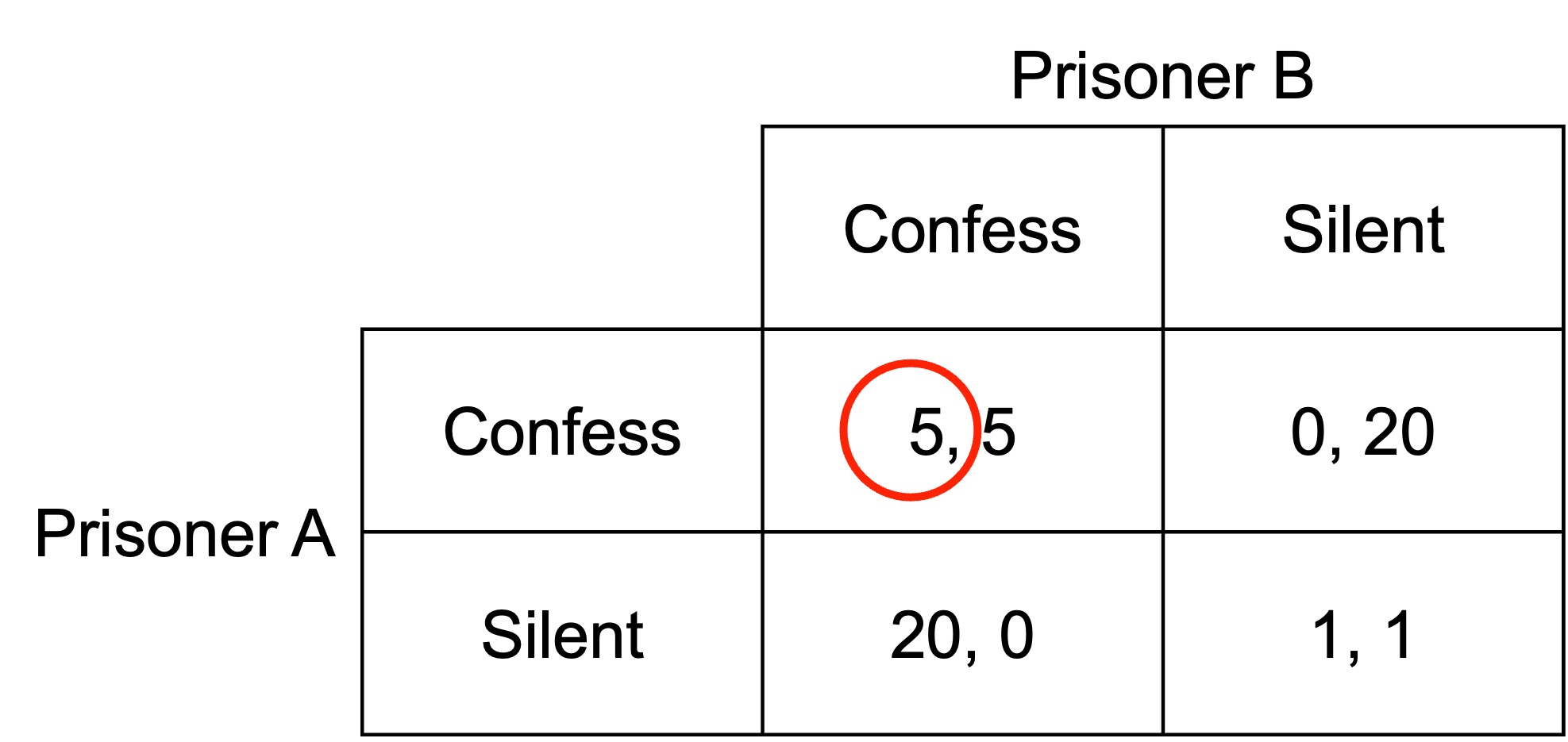

Equipped with the normal form of the game, we can determine what each player wants to do in response to each action of the other player.

For example, we can see that if Prisoner B confesses, Prisoner A can either confess and receive five years in prison, or remain silent and receive 20 years in prison. They would choose to confess.

We indicate the preferred action in response to another player’s action by circling the relevant payoff. For example:

If Prisoner B remains silent, Prisoner A could either confess and escape without a sentence, or remain silent and receive a sentence of one year in prison. They would prefer to confess.

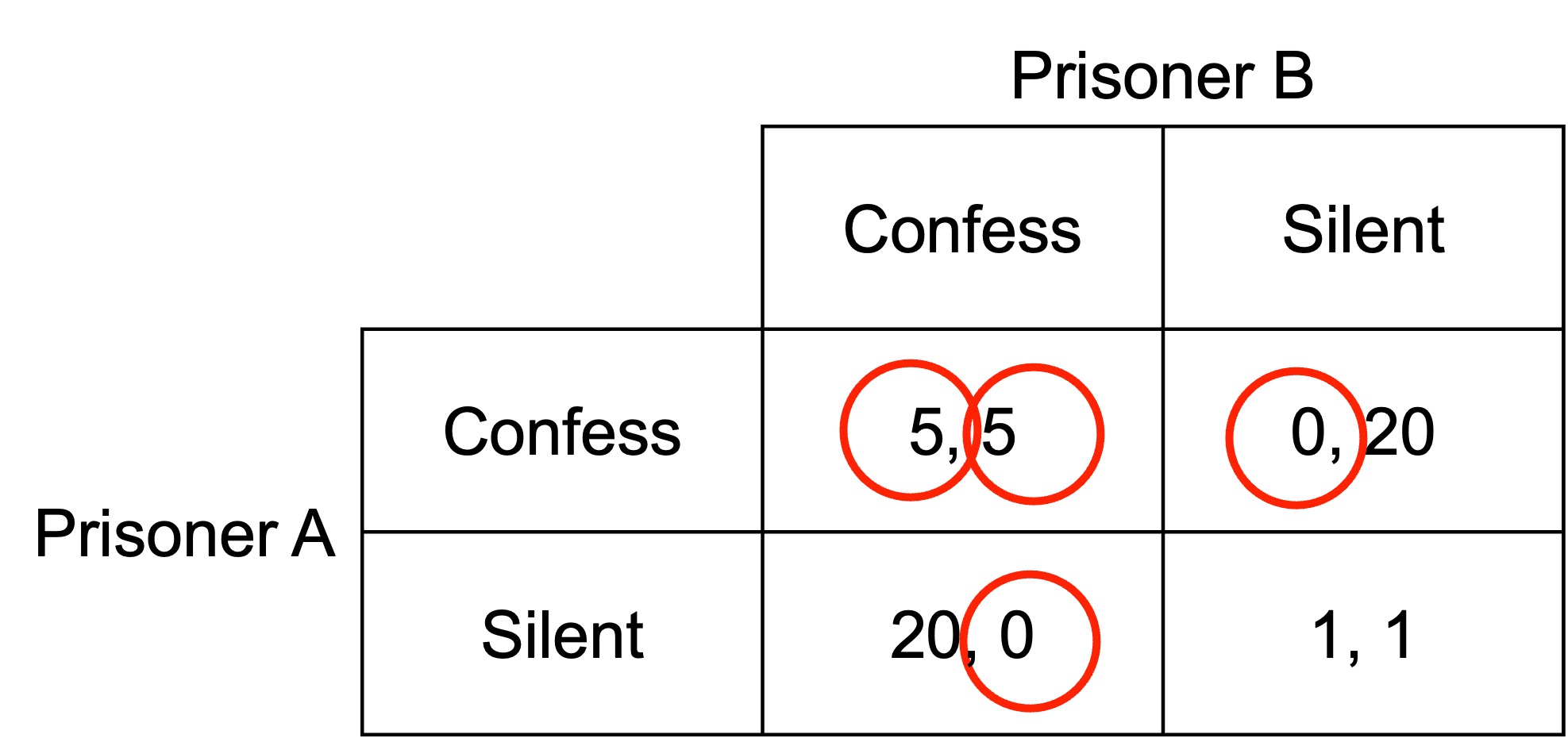

We can then work through the same process for Prisoner B’s actions.

If Prisoner A confesses, Prisoner B can either confess and receive five years in prison, or remain silent and receive 20 years in prison. They would choose to confess.

If Prisoner A remains silent, Prisoner B could either confess, and escape without a sentence, or remain silent, and receive a sentence of one year in prison. They would prefer to confess.

Indicating this set of preferred actions in response to that of the other player gives us this completed matrix.

40.3 Dominant strategies

Before examining this matrix further, I will now introduce the concept of the dominant strategy.

A strategy is dominant if it gives a higher payoff than every other strategy, for every strategy that your rivals play.

A strategy is strictly dominant if it gives a strictly higher payoff than every other strategy, for every strategy that your rivals play.

If you have a strictly dominant strategy, you should play it for sure.

In a dominant strategy equilibrium, all players choose a dominant strategy.

In the prisoner’s dilemma, both players have a dominant strategy to confess. No matter what the other player does, confessing is better than remaining silent.

40.4 Nash equilibrium

Another important concept is the Nash equilibrium.

A set of strategies is a Nash equilibrium if every player is playing a best response to their rivals’ strategies. No one has an incentive to change strategy.

A Nash equilibrium is self-enforcing and stable. If the players agree to play a certain way, they’ll both do it. Unilateral deviations are not worthwhile.

The prisoner’s dilemma has a single Nash equilibrium: (Confess, Confess). Visually, where the preferred response of both players to the other player’s action falls within the same cell, this indicates a Nash equilibrium.

40.5 Simultaneous-move one-shot game examples

In this part, I will show some examples of simultaneous-move one-shot games.

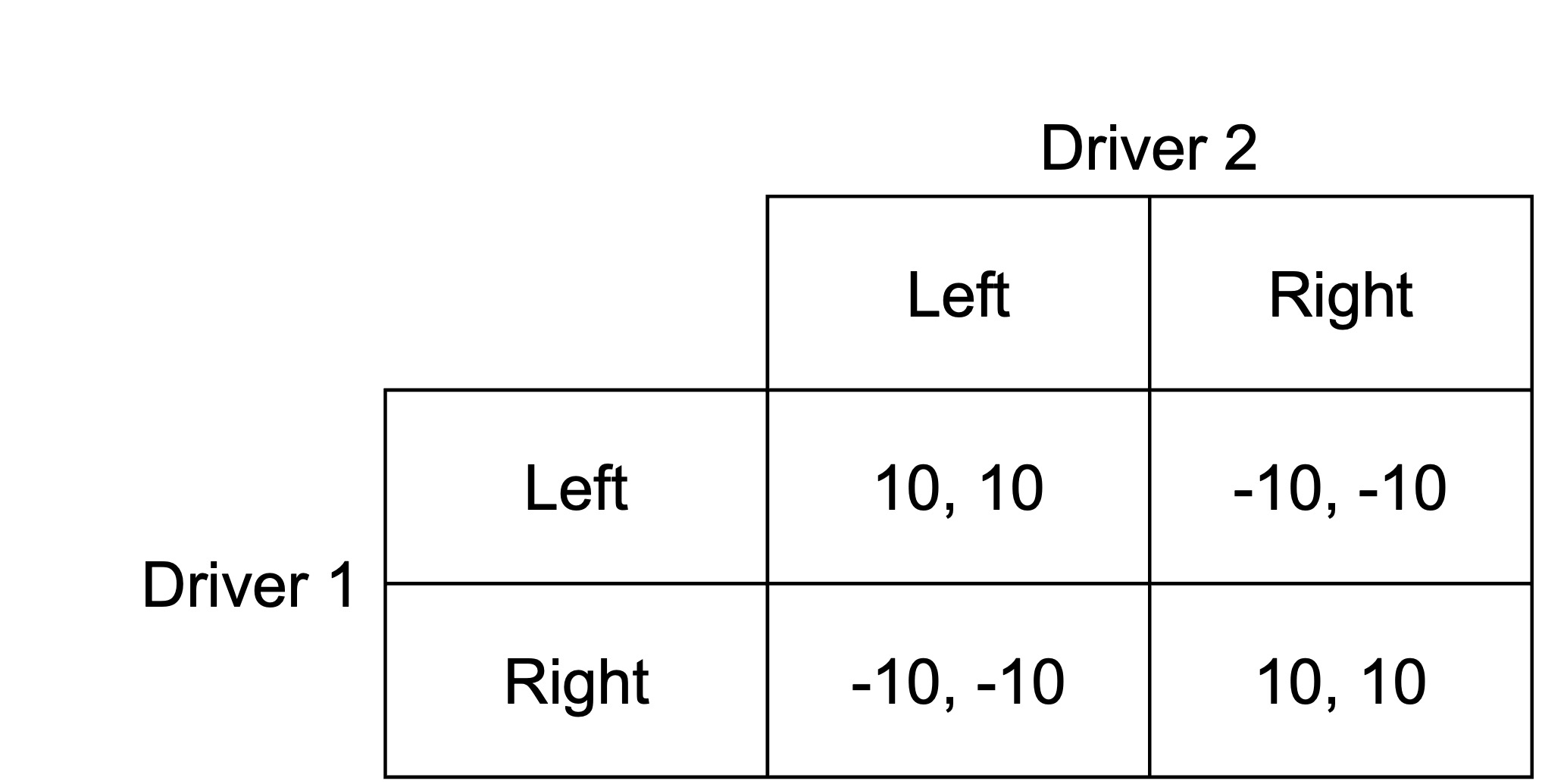

40.5.1 The driving game

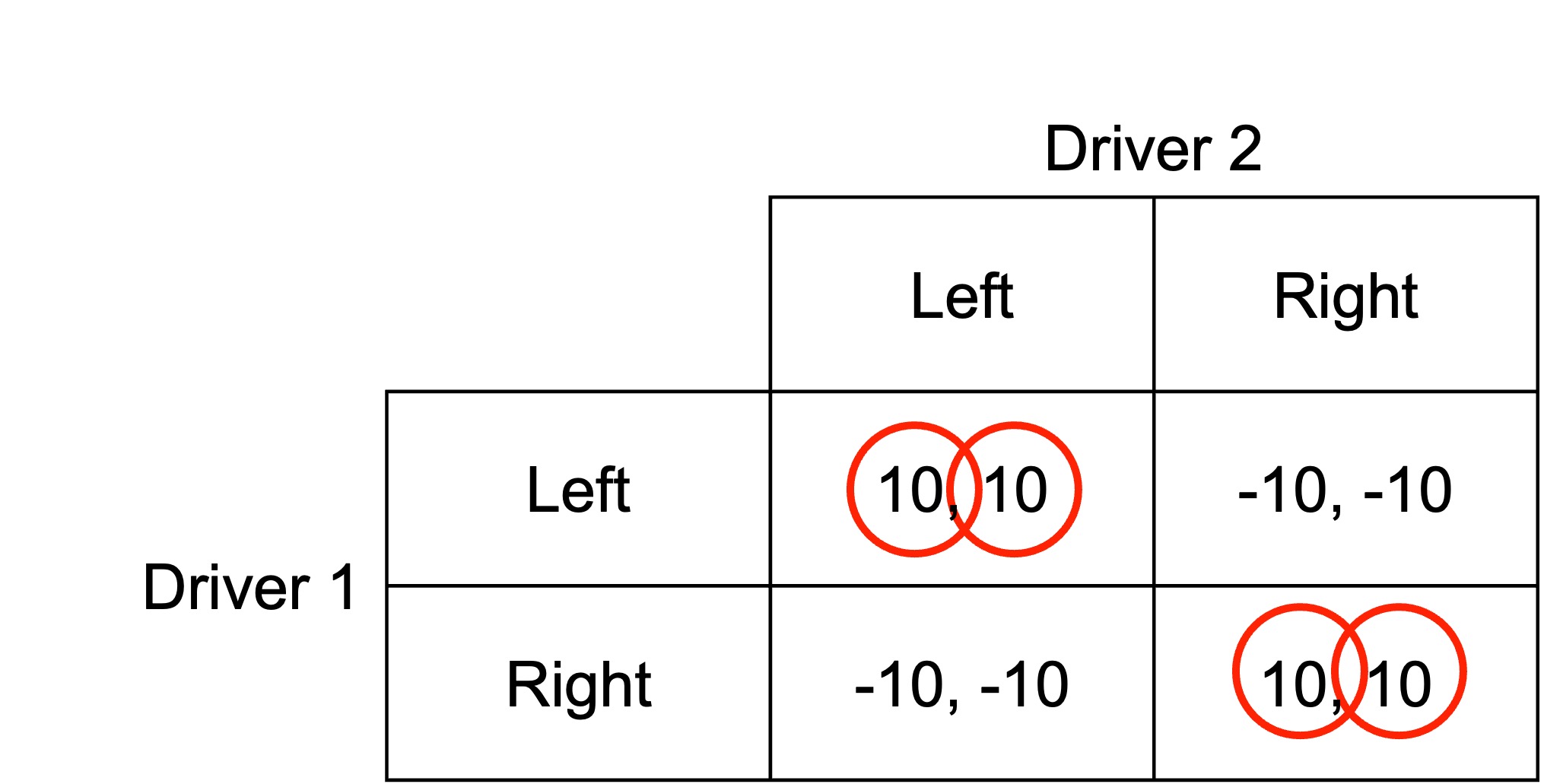

Consider the following game between two players deciding what side of the road to drive on. They can drive on the left or the right. If they both drive on the left or right when they approach each other, they will successfully pass. If one drives on the left and the other on the right, they will crash.

What are the Nash equilibria?

If Driver 2 drives on the left, Driver 1 can either successfully drive on the left, or drive on the right and crash. They would choose to drive on the left. If Driver 2 drives on the right, Driver 1 can either successfully drive on the right, or drive on the left and crash. They would choose to drive on the right.

Similarly, if Driver 1 drives on the left, Driver 2 can either successfully drive on the left, or drive on the right and crash. They would choose to drive on the left. If Driver 1 drives on the right, Driver 2 can either successfully drive on the right, or drive on the left and crash. They would choose to drive on the right.

We can see from the matrix that there are two Nash equilibria. The Nash equilibria are (Left, Left) and (Right, Right). If both drivers are driving on the left, neither has an incentive to change their strategy. If both drivers are driving on the right, again, neither has an incentive to change.

40.5.2 Matching pennies

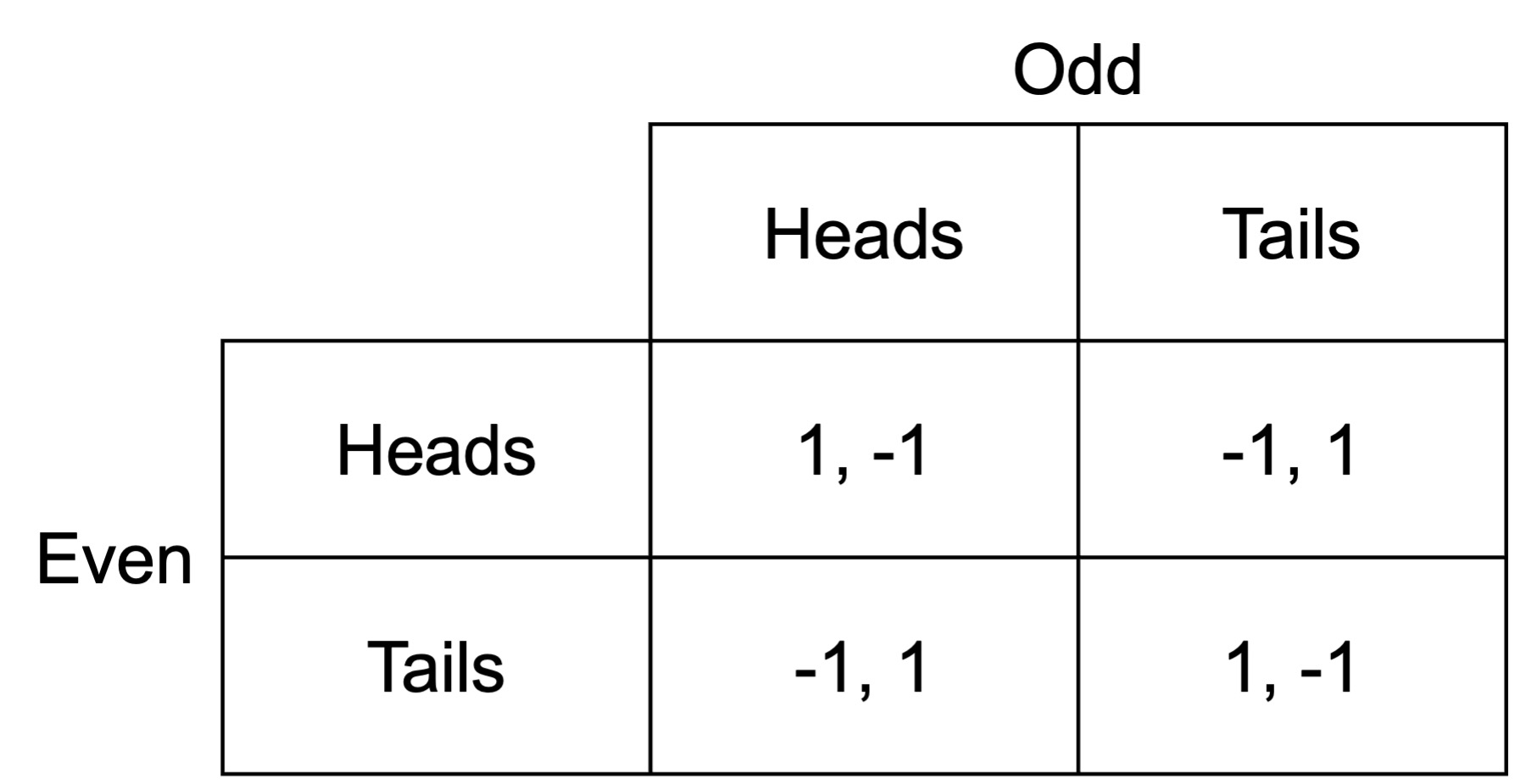

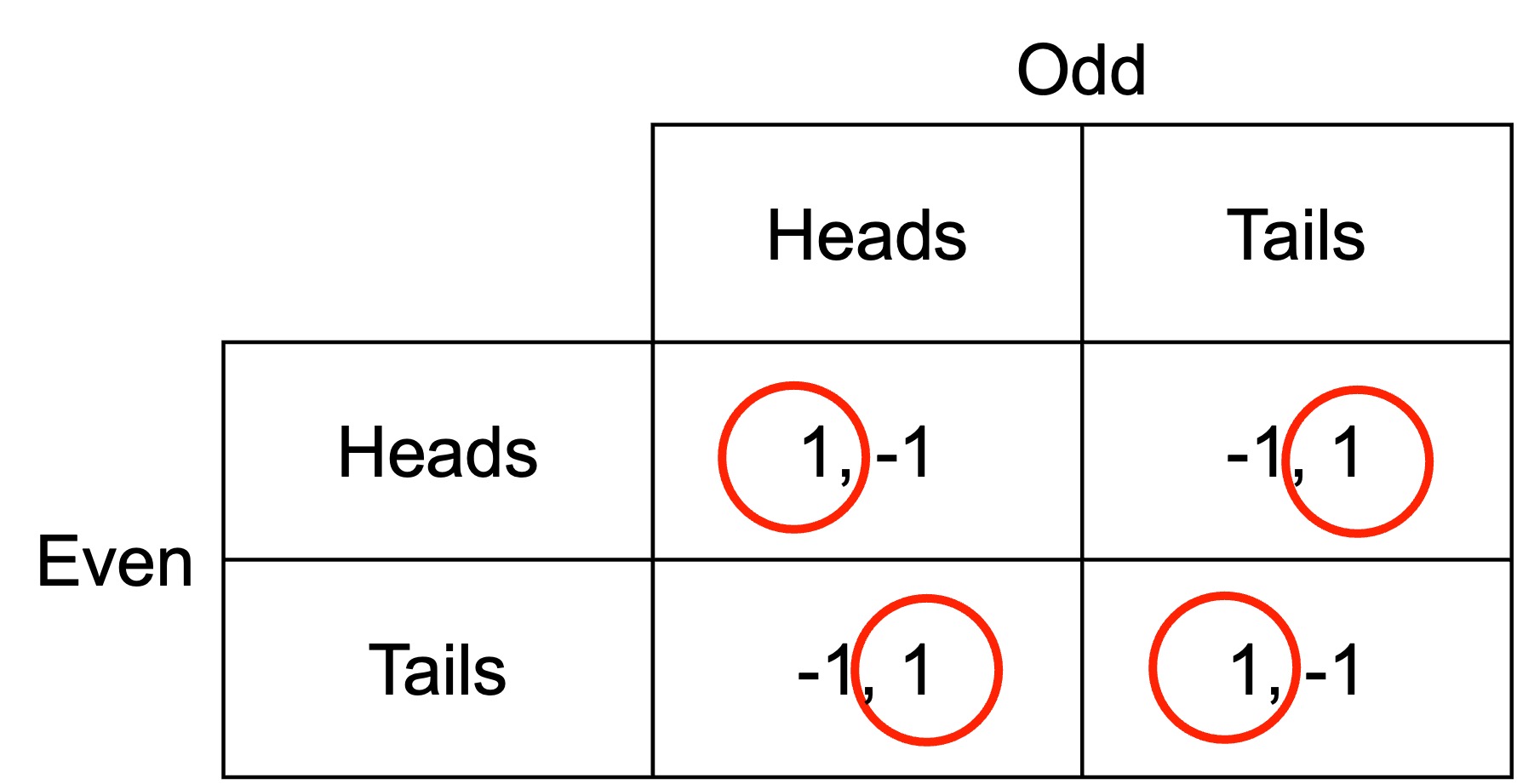

The next game, called matching pennies, involves two players, Even and Odd, who each have a penny. Each player must select one side of the penny and simultaneously show the penny to the other player. If the pennies match, Even wins. If they don’t match, Odd wins.

What are the Nash equilibria?

To determine this, we work through the matrix as we did in the previous example.

If Odd shows heads, Even can either show heads and win, or show tails and lose. They would choose to show heads. If Odd shows tails, Even can either show tails and win, or show heads and lose. They would choose to show tails.

Similarly, if Even shows heads, Odd can either show tails and win, or show heads and lose. They would choose to show tails. If Even shows tails, Odd can either show heads and win, or show tails and lose. They would choose to show tails.

There are no pure-strategy Nash equilibria for this game. For any combination of heads and tails, one of the players would want to change their choice.

There are what are called “mixed-strategy Nash equilibria” in this game, but mixed-strategy equilibria are beyond the scope of this subject.

40.5.3 The stag hunt

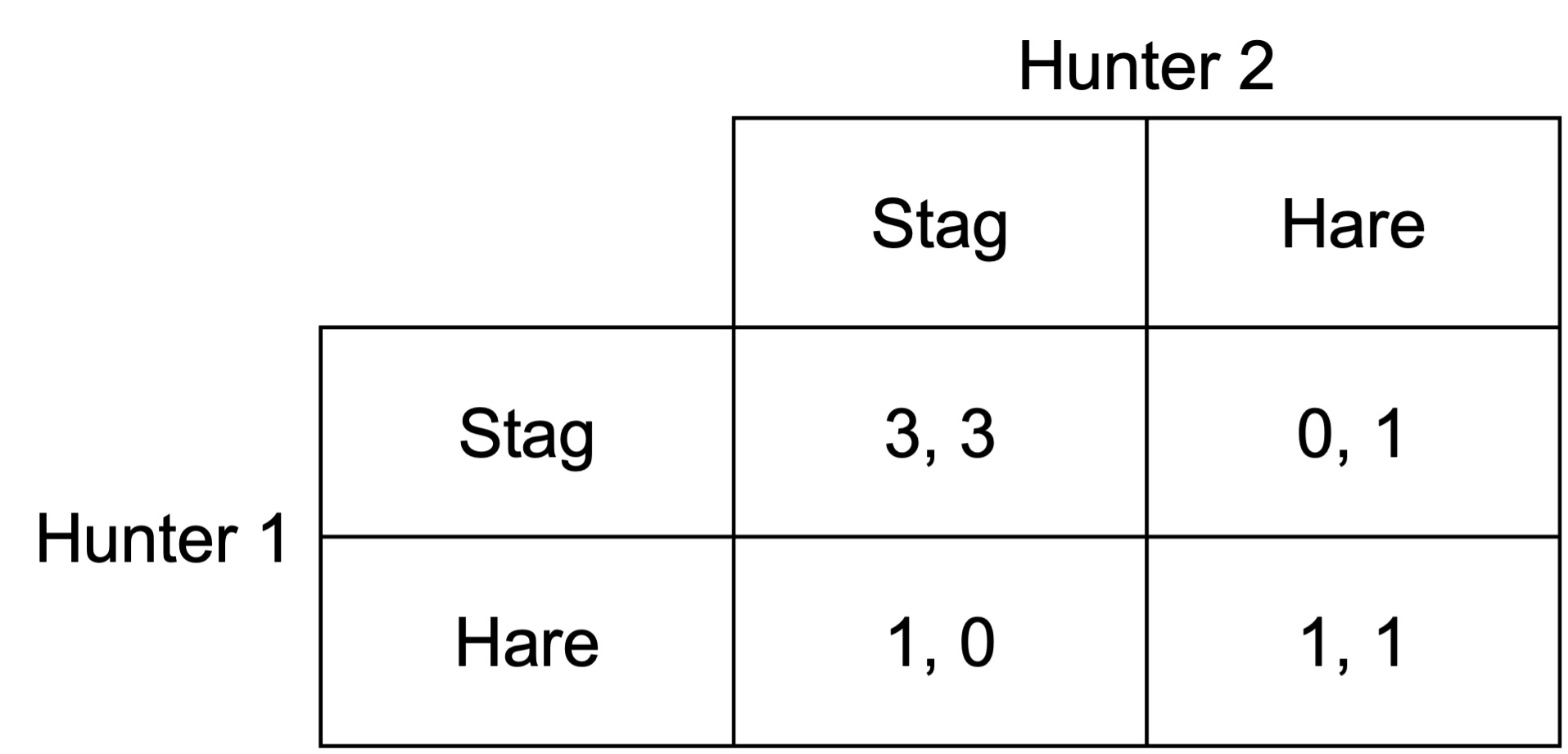

Consider the “stag hunt game” between two players deciding what animal they will hunt. Both hunters need to cooperate to catch the stag. They can catch a hare by themselves, but it provides less meat.

What are the Nash equilibria?

If Hunter 2 hunts the stag, Hunter 1 can either hunt the stag and catch it, or hunt the hare and catch it. They would choose to hunt the stag as it gives a payoff of 3 compared to 1. If Hunter 2 hunts the hare, Hunter 1 can either hunt the stag and not catch it, or hunt the hare and catch it. They would choose to hunt the hare as it gives a payoff of 1 compared to 0.

Similarly, if Hunter 1 hunts the stag, Hunter 2 can either hunt the stag and catch it, or hunt the hare and catch it. They would choose to hunt the stag as it gives a payoff of 3 compared to 1. If Hunter 1 hunts the hare, Hunter 2 can either hunt the stag and not catch it, or hunt the hare and catch it. They would choose to hunt the hare as it gives a payoff of 1 compared to 0.

The Nash equilibria are (Stag, Stag) and (Hare, Hare). On either pair of strategies, neither player has incentive to change. It is an open question, however, as to which Nash equilibrium might emerge if they were to play the game.

40.5.4 The public goods game

The final game I will consider in this part is the public goods game.

In this game, each participant is given an initial endowment.

Each participant secretly and simultaneously chooses how much of their endowment they wish to contribute to a public pot.

The money in the public pot is multiplied by some amount and split evenly between the players. Typically, the multiple applied to the pot is greater than 1, but less than the number of players.

For example, five players might each be given $10, with the pot doubled. Suppose they each contribute $5 of their $10 endowment to the pot. The $25 contributed to the pot is multiplied by 2 to a total of $50. Each player then receives $10 from the pot, giving them $15 in total.

In Nash equilibrium in the public goods game, nobody transfers anything to the pot. Any contributions are split between all players, so if there are more players than the multiple, which is normally the case by design, contributions result in a loss to that individual player.

Consider the previous game, but this time Player E contributes nothing. There is then $20 in the pot, which is doubled to $40. The pot is then split equally between the players, each receiving $8 from the pot. The result is that Player E is better off having not contributed, ending with $18, compared to the $15 they would have received had they contributed $5 like the other players.

The Pareto optimal result, however, is for all players to contribute their full endowment and each receives back their multiplied contribution. However, the Pareto optimal result is not stable, as each player has an incentive to defect and contribute nothing.