45 Level-k thinking

Summary

- Level-k thinking is a model of strategic reasoning where players try to be “one step ahead” of others. A level-k player assumes others are level-(k-1) and responds optimally to that assumption.

- Level-0 players are non-strategic, often modelled as randomizing across all strategies. Level-1 players assume others are level-0, level-2 assumes others are level-1, and so on.

- The p-beauty contest game illustrates level-k thinking. In this game, players choose numbers, aiming to be closest to (p) times the average of all choices. Different levels of thinking lead to different number choices, with experimental results often showing a mix of level-1, level-2, and level-3 players.

45.1 Introduction

The idea behind level-k thinking is that a player forms an expectation of what others will do and tries to be “one step ahead”.

That is, a level-k player plays the best response to level-(k-1) players.

Level-0 players do not engage in strategic thinking. This is usually modelled as randomisation across all strategies.

Level-1 players assume other players are level-0 and act optimally conditional on this assumption.

Level-2 players assume other players are level-1 and act optimally conditional on this assumption.

And so on.

45.2 Examples

45.2.1 The beauty contest

To understand level-k thinking, consider the following thought experiment from Keynes (1936).

[P]rofessional investment may be likened to those newspaper competitions in which the competitors have to pick out the six prettiest faces from a hundred photographs, the prize being awarded to the competitor whose choice most nearly corresponds to the average preferences of the competitors as a whole; so that each competitor has to pick, not those faces which he himself finds prettiest, but those which he thinks likeliest to catch the fancy of the other competitors, all of whom are looking at the problem from the same point of view. It is not a case of choosing those which, to the best of one’s judgment, are really the prettiest, nor even those which average opinion genuinely thinks the prettiest. We have reached the third degree where we devote our intelligences to anticipating what average opinion expects the average opinion to be. And there are some, I believe, who practise the fourth, fifth and higher degrees.

This thought experiment has since been developed into a game, the p-beauty contest (Moulin (1986)).

In the p-beauty contest, each of n players pick a number y\in[0,100].

The winner is the player whose chosen number is closest to the mean of all the chosen numbers (\bar y) multiplied by a parameter p. That is, the winner is the player with their chosen number closest to p\bar y.

p is typically chosen such 0\leq p\leq 1, with p=1/2 and p=2/3 common.

How might level-k players play this game?

Suppose p=2/3.

A level-0 player does not think strategically. We will have the level-0 player randomly select a number between 0 and 100.

The level-1 player will play the best response to level-0 players. If level-0 players select across the interval [0, …, 100], the best response is:

y_1=\frac{2}{3}\bar y=\frac{2}{3}\times 50=33.3

The level-2 player will play the best response to level-1 players. If all other players are level-1 and select 33.3, the best response is:

y_2=\frac{2}{3}\bar y=2/3\times 33.3=22.2

The level-3 player will play the best response to level-2 players. If all other players are level-2 and select 22.2, the best response is:

y_3=\frac{2}{3}\bar y=2/3\times 22.2=14.8

And so on.

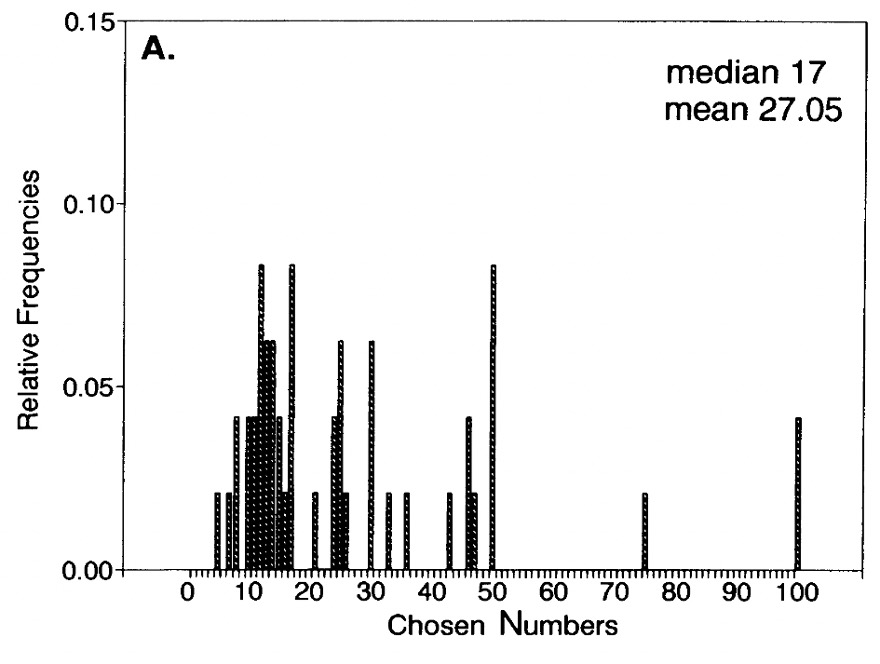

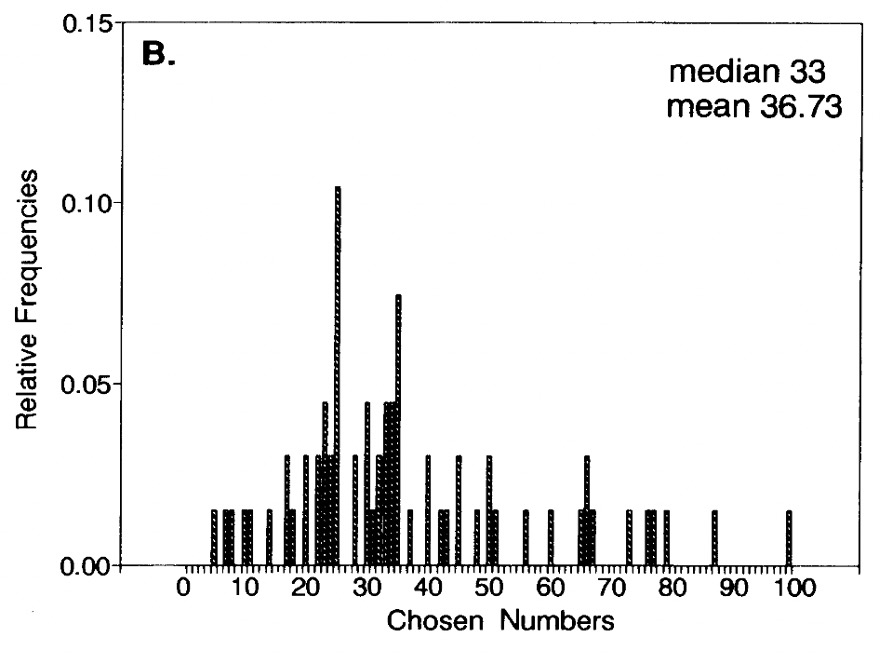

The following charts come from Nagel (1995), with p=1/2 and p=2/3. The charts show the distribution of chosen numbers in the p-beauty contest.

The chart with p=2/3 spikes at 22.2 and 33.3, suggesting players are playing at level-2 and level-1, respectively. This matches with other experimental evidence on the p-beauty game, with few level-0 players. Most are level-1, level-2 and level-3.

The lab evidence doesn’t necessarily imply that level-k is the “right model”. Data and theory appear to match, but it is hard to know whether this is how subjects are thinking.

Finally, it is worth noting that in the Nash equilibrium, each player picks 0. This is because the best response to all other players picking 0 is to pick 0. For any higher number, everyone has an incentive to lower their choice. However, if playing against level-k players, selecting 0 is not the best approach.

45.2.2 The assignment game with level-k thinking

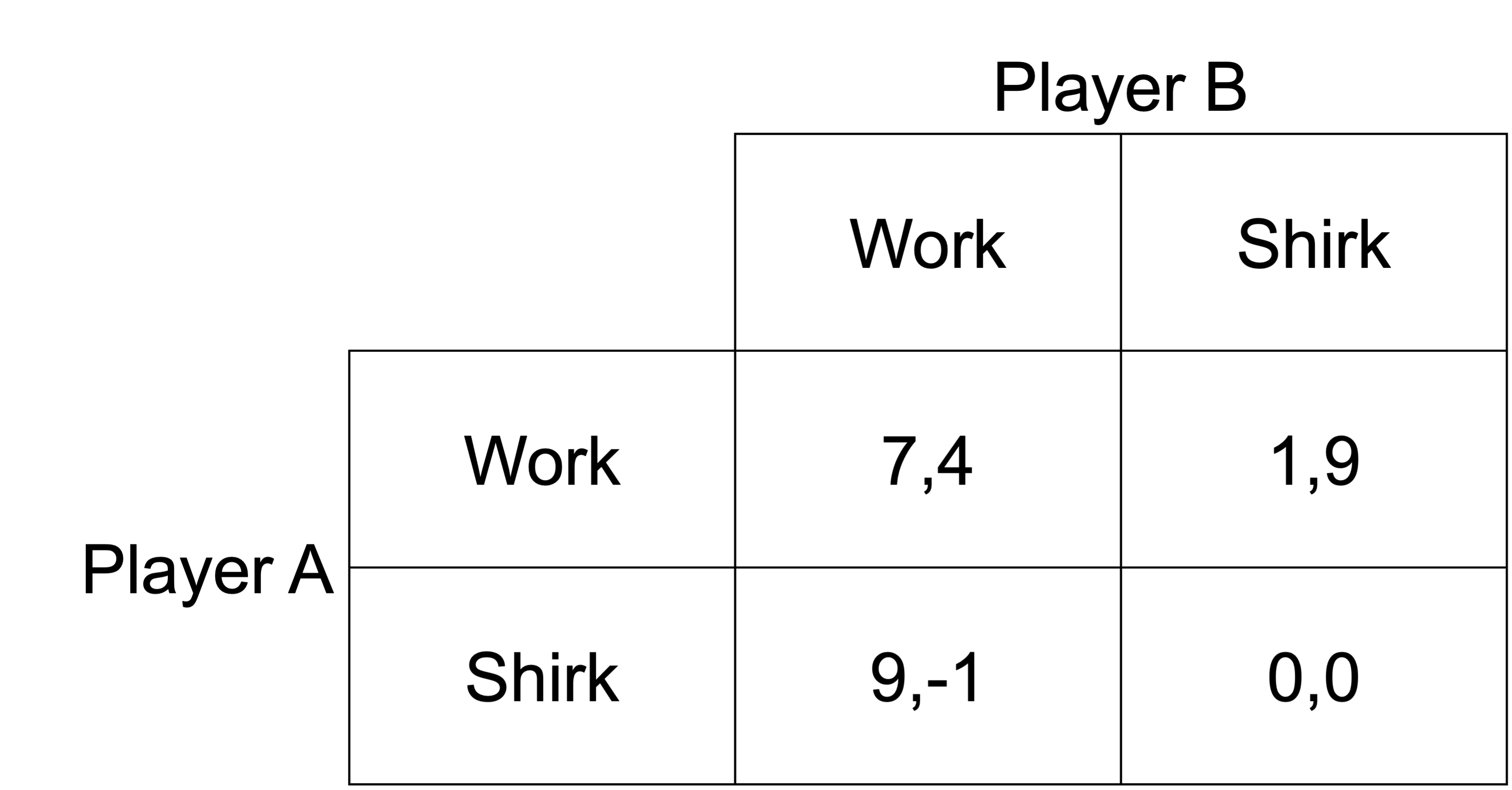

Let’s consider another example of level-k thinking involving a game called the assignment game.

Each player needs to decide if they will work or shirk. If they both work, they receive a good payoff. They receive an ever better payoff, however, if they shirk while the other works.

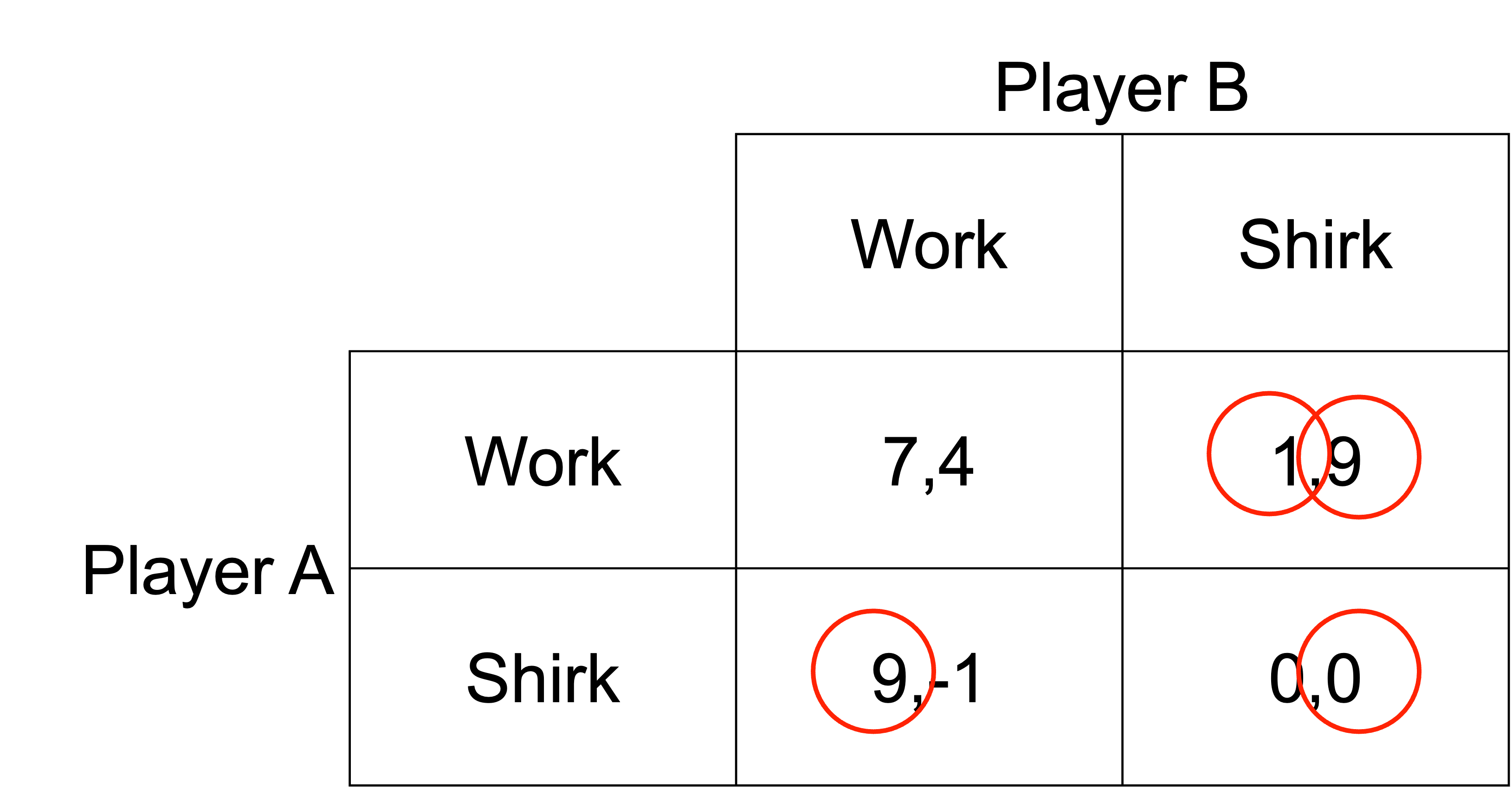

Working through the payoffs for each player, if player B works, player A is better off shirking, receiving payoff of 9. If player B shirks, player 1 is better off working, receiving payoff of 1. If player A works, player 2 is better off shirking, receiving payoff of 9. If player A shirks, player B is still better off shirking, receiving payoff of 0.

There is a unique Nash equilibrium (work, shirk), with shirk the dominant strategy for Player B.

Consider, however, if instead of fully rational agents, we have level-k thinkers playing the game.

In this case, the outcome of the game will depend on the level of thinking of each player.

If both players are level-0, they will each play randomly.

At level-1, each player will play the best response to level-0 players. Each player determines this by calculating their best response to the random strategy of the other player.

For player A, their expected payoffs are calculated using the 50% probability with which player B could play each action.

The expected payoff from playing work is:

\frac{1}{2}\times 7+\frac{1}{2}\times 1=4

The expected payoff from playing shirk is:

\frac{1}{2}\times 9+\frac{1}{2}\times 0=4.5

A level-1 player A chooses to shirk.

For player B, their expected payoff from playing work is:

\frac{1}{2}\times 4+\frac{1}{2}\times -1=1.5

Their expected payoff from playing shirk is:

\frac{1}{2}\times 9+\frac{1}{2}\times 0=4.5

A level-1 player B also chooses to shirk.

If a player has a dominant strategy, they discover it at k=1. Any level-k thinker will always uses the dominant strategy for k\geq 1. In that case, we know that any player B with k\geq 1 will shirk.

What if each player is level 2?

Player A calculates their best response to a level-1 player B. A level-1 player B always plays shirk. Player A’s best response to shirk is to work. The level-2 player A works.

Although we know a level-2 player B will shirk as as shirk is their dominant strategy, we can show this by considering their best response to a level-1 player A. A level-1 player A always plays shirk. Player B’s best response to shirk is to shirk. The level-2 player B shirks.

At a certain level of thinking, the players will discover the Nash equilibrium. Here, they have discovered it at level-2 thinking. For any higher level of thinking, they will remain at the Nash equilibrium. That is, if players endowed with level k=\bar k rationality play Nash, all players with k>\bar k play Nash.

| Level-k | Player A | Player B |

|---|---|---|

| k=0 | Random | Random |

| k=1 | Shirk | Shirk |

| k=2 | Work | Shirk |

| k=3 | Work | Shirk |

| k=4 | Work | Shirk |

45.2.3 Centipede game

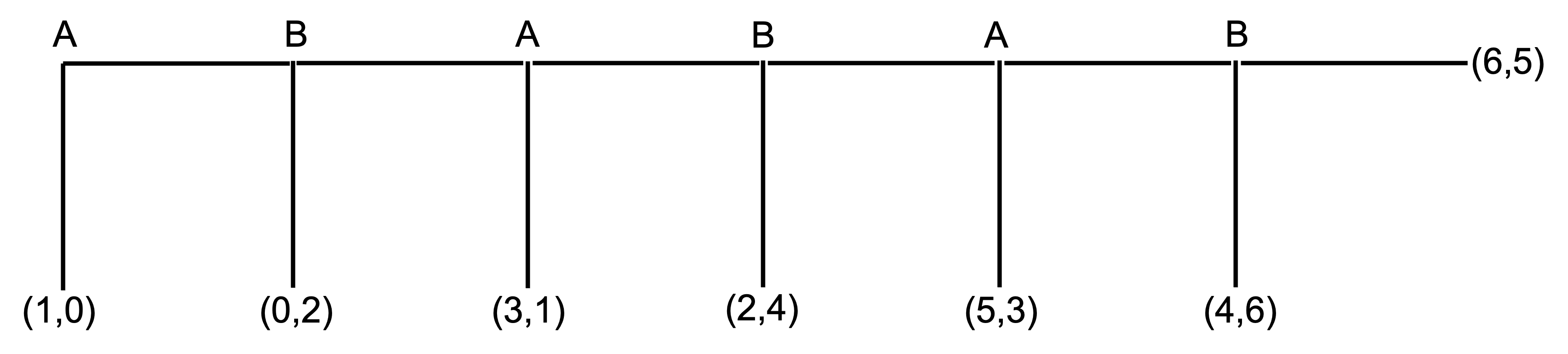

Another example of level-k thinking is the centipede game.

This centipede game has six stages. At each stage, a player can “take” and end the game or they can “pass”, increasing the total payoff. The other player then has a move.

The numbers 1 and 2 along the top of the centipede represent the decision nodes for two players. At the first node, player 1 has the choice to take or pass. If player 1 passes, player 2 has the choice to take or pass, and so on. At the final node, the game ends regardless of what player 2 chooses.

The payoff when a player takes and ends the game is represented by the numbers in the brackets. The first number is the payoff for player A and the second number is the payoff for player B.

There is a unique subgame perfect equilibrium for the centipede game: S_1=(\text{take, take, take}) and S_2=(\text{take, take, take}), where S_1 and S_2 are the set of strategies for player A and player B respectively. We solve for this in Section 41.3.1.

What do people do when playing the centipede game in the lab?

People tend to pass until a few stages before the end (depending on the length of the centipede) and then take. They do not play the Nash equilibrium strategy.

Can level-k thinking provide insight into this behaviour?

Suppose a level-0 player passes until the end. They are possibly lucky if they are player A playing against another level-0 player.

A level-1 player B would take at (4,6) as the level-0 player A would pass until then. A Level-1 player A would be planning to take (6,5) at the end as they believe the level-0 player B will keep passing.

A level-2 player B would plan to take at the final stage (4,6) as they believe the level-1 player A passes. A level-2 player A would take the payoff at (5,3) as they believe a level-1 player B would take at (4,6).

A level-3 player B would plan to take at (2,4) as they believe the level-1 player A will take at (5,3). A level-3 player A would plan to take at (5,3) as they believe a level-2 player B would take at (4,6).

And so on.