38 Overconfidence

Summary

- Overconfidence is a robust finding in judgment and decision-making research, but it actually encompasses three distinct phenomena: overprecision, overestimation, and overplacement.

- Overprecision is the tendency to believe our predictions or estimates are more accurate than they are, often demonstrated in confidence interval tasks.

- Overestimation is the belief that we can perform better than we realistically can, typically occurring for difficult tasks but not for easy ones.

- Overplacement is the erroneous judgment that we are better than others, which varies with task difficulty. People tend to overplace on easy tasks and underplace on difficult ones.

- Overconfidence has been linked to real-world phenomena such as excessive firm entry in markets and over-trading in financial markets, with experiments and studies demonstrating how it can lead to suboptimal outcomes in these domains.

38.1 Introduction

De Bondt and Thaler (1995) wrote “Perhaps the most robust finding in the psychology of judgment and choice is that people are overconfident.”

Take the following examples:

A person is asked to estimate the length of the Nile by providing a range that the respondent is 90% sure contains the correct answer. For example, they might answer that there is a 90% probability that the Nile is between 2500km and 5000km long. However, when people answer this question, the estimate typically contains the correct answer only 50% of the time.

PGA golfers typically believe they sink around 75% of 6-foot putts – some even believe they sink as many as 85% – when the average is closer to 55%.

93% of American drivers rate themselves as better than average. 25% of high school seniors believe they are in the top 1% in their ability to get along with others.

There are many similar examples, all making the case that people are generally overconfident.

But despite each being labelled as overconfidence, note that these examples are three different phenomena.

Overprecision is the tendency to believe that our predictions or estimates are more accurate than they are. The typical study seeking to show overprecision asks for someone to give confidence ranges for their estimates, such as estimating the length of the Nile.

Overestimation is the belief that we can perform at a level beyond that which we realistically can. The evidence here is mixed. We typically overestimate when attempting a difficult task, such as a six-foot putt. But on easy tasks, the opposite is often the case – we tend to underestimate our performance. Whether over or underestimation occurs depends upon the domain.

Overplacement is the erroneous relative judgement that we are better than others. Obviously, we cannot all be better than average. But this relative judgement, like overestimation, tends to vary with task difficulty. For easy tasks, such as driving a car, we overplace and consider ourselves better than most. But, people will rate themselves below average for a skill such as drawing or identifying plants from the Amazon. People don’t suffer from pervasive overplacement. Whether they overplace depends on what the situation is.

You might note that we tend to both underestimate and overplace our performance on easy tasks. We can also overestimate but underplace our performance on difficult tasks.

So, are we both underconfident and overconfident at the same time? The blanket term of overconfidence does little justice to what is occurring.

The conflation of these different effects under the umbrella of overconfidence often plays out in stories of how overconfidence (rarely assessed before the fact) led to someone’s fall. For instance, evidence that people tend to believe they are better drivers than average (overplacement) is not evidence that overconfidence led someone to pursue a disastrous corporate merger (overestimation).

38.2 Firm entry

An example of overconfidence in action can be seen in firm entry.

Most new businesses fail within a few years. For example, one study of US manufacturers found over 60% of entrants had exited within five years and almost 80% within 10 years.

Camerer and Lovallo (1999) ran an experiment to test whether business failure may be due to optimism about their relative skill.

The lab experiment involved a set of markets. Those who chose to participate in a market were paid a set amount according to their rank within the market. Those ranked within the “market capacity” would share a payment of $50. Those beyond the market capacity would be penalised $10. Accordingly, if there are 5 entrants above market capacity, the expected payoff of all entrants is zero. More than that and it is negative.

The rank in the market was determined by either luck, through a random draw, or a test of skill involving logic puzzles or trivia questions about sports or current events.

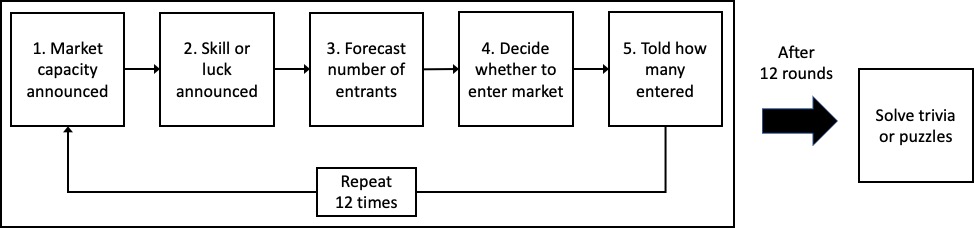

In each round of the experiment, the market capacity was announced to the players, along with whether the payoffs in the market were based on luck or skill. The participants were then asked to forecast the expected number of entrants (for which they earn a payment if correct) and decide simultaneously and without communicating whether to enter into the market. Subjects were then told how many participants had entered.

After all of the rounds, students solved puzzles or took the trivia quiz to determine their skill rank.

The results of the experiment showed that more participants entered the market when the ranking was based on skill than if based on random draw. This indicates a belief that their skill level will rank them higher than a random draw: they are above average.

An interesting element to this experiment was that for some of the markets the participants were recruited by being asked if they would like to volunteer for an experiment in which performance would depend on their performance on sports or current event trivia questions. Hence the pool in those markets would be stronger than typical.

In those markets with self-selected participants, market entry was even higher, and payoffs were negative in most rounds. This suggests the self-selected entrants were overconfident in their skill due to what Camerer and Lovallo call “reference group neglect”. The participants seem to neglect that the others in the reference group also self-selected in to the experiment and think they are skilled too.

Moore et al. (2007) also ran an experiment on firm entry and found, like Camerer and Lovallo, that entrepreneurs overweight personal factors and underweight competitors when making entry decisions. However, when they varied the task difficulty, they found excess entry only when the industry appeared an easy one in which to compete. When it appeared difficult, too few entered. People overplaced in easy markets and underplaced in hard ones.

38.3 Trading

Another domain where overconfidence has been argued to play a role is related to trading.

A consistent finding in the analysis of trading behaviour is that more trading leads to poorer outcomes. The higher transaction costs are not compensated through higher returns.

To test whether over-trading may be linked to overconfidence, Barber and Odean (2001) examined investors by gender. Men tend to be more overconfident than women - a point they support with evidence of overprecision, overplacement and overestimation. If overconfidence leads to more trading, you would predict that men would trade more than women.

Barber and Odean (2001) examined trading account data from over 35,000 households for the period from February 1991 to January 1997. They found that men traded 45 percent more than women, reducing their net returns by 2.65 percentage points a year as opposed to 1.72 percentage points for women.