Heuristics and biases

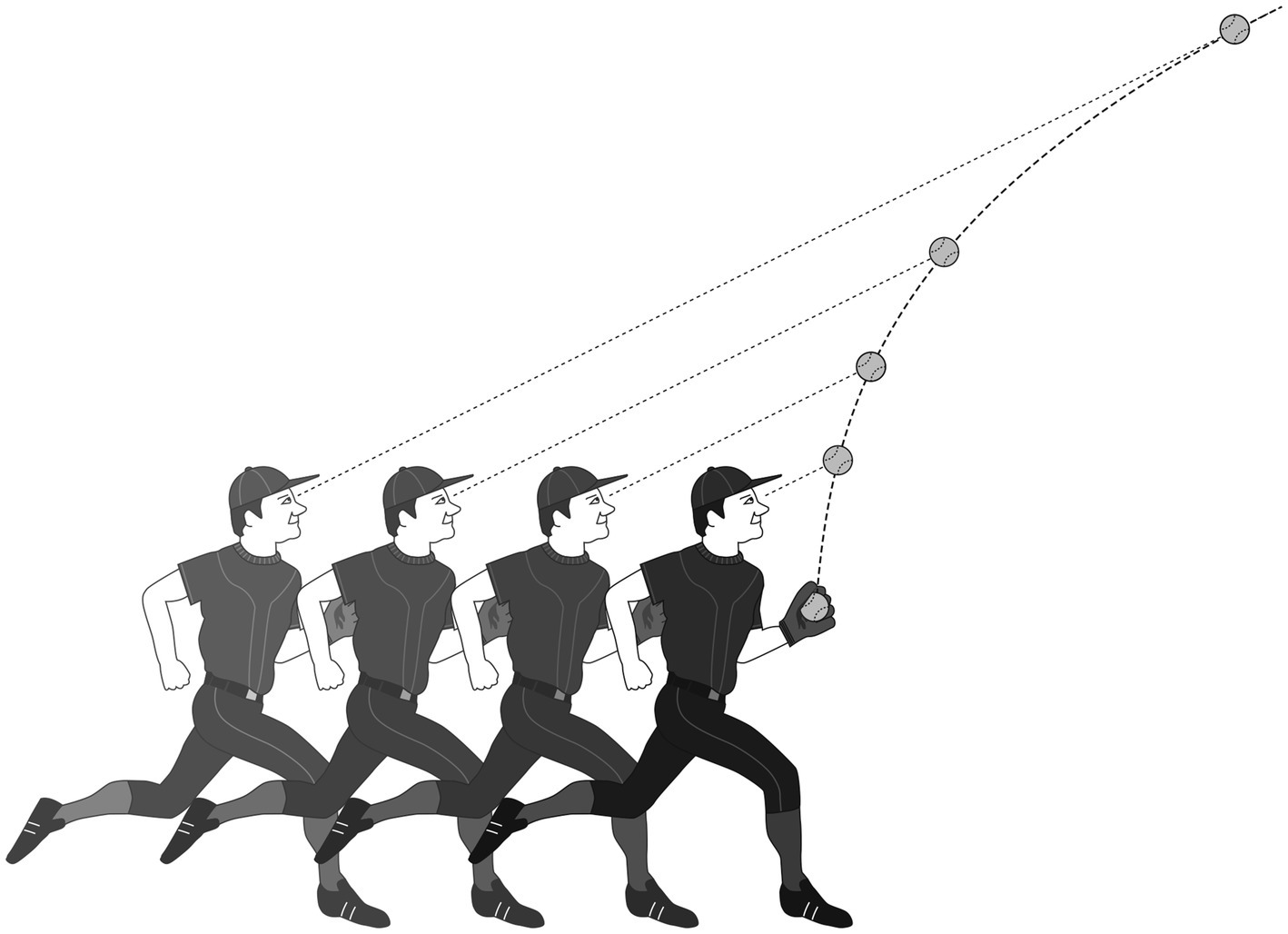

Imagine you are trying to catch a ball.

One strategy would be to calculate the ball’s trajectory - that is, it’s speed, angle, and spin - make some adjustments for wind resistance. You then move to the spot where the ball will land.

Another would be to use a simple rule: keep your eye on the ball and maintain a constant angle of gaze as you move. This mental shortcut - known as the gaze heuristic - works remarkably well. Yet this same strategy can lead you to run in a curved path rather than straight to where the ball will land. It might lead to first run away and then run toward the landing point.

This approach to catching a ball is an example of a heuristic - a mental shortcut. Heuristics are essential tools that help us navigate a complex world with constrained cognitive bandwidth. But heuristics can also lead to systematic biases.

In this part, I will explore how we use heuristics to form judgments and make decisions under uncertainty. I will examine how these mental shortcuts can lead to biases and errors in our reasoning.

First, I’ll examine fundamental heuristics that people commonly use when assessing probabilities and making predictions. I’ll cover the representativeness heuristic (judging probability by similarity to prototypes), the availability heuristic (estimating frequency based on how easily examples come to mind), and anchoring and adjustment (using initial values as reference points for estimates).

Building on this foundation, I’ll then analyse specific biases that emerge in probability judgments. We’ll explore the conjunction fallacy (judging combinations of events as more likely than individual events) and base-rate neglect (failing to consider background probabilities). We will also consider two famous biases that we encounter in the world of sports and gambling: the hot-hand fallacy and the gambler’s fallacy.

We will then look at how heuristics can actually serve as effective decision-making tools rather than just sources of error. Through the lens of the bias-variance trade-off, we’ll see how simpler heuristic approaches can sometimes outperform more complex strategies.

Finally, I’ll examine overconfidence, an inability to calibrate the accuracy of our judgments. I will look at three dimensions of overconfidence, being overprecision, overestimation, and overplacement. We’ll explore how these manifest in real-world decision-making contexts.

This exploration will give us a richer understanding of how people actually make probabilistic judgments, rather than just how they theoretically should. This provides crucial insights for analysing decision-making under uncertainty.