26 Sophisticated present bias

Summary

- Present-biased agents can be categorised as naive or sophisticated, based on their awareness of future preference reversals.

- Naive agents incorrectly believe their future selves will discount rewards consistently, leading to time-inconsistent choices.

- Sophisticated agents accurately predict their future preference reversals and plan accordingly.

- Naive agents use forward reasoning in decision-making, while sophisticated agents use backward reasoning.

- The following examples show that the decision-making processes of naive and sophisticated agents can lead to different choices, even with identical discount factors.

- Sophisticated agents may sometimes choose worse immediate outcomes to avoid even worse future outcomes due to anticipated preference reversals. They tend to take action earlier than naive agents, a behaviour known as “prepoperation”.

26.1 Introduction

Suppose a present-biased agent considers whether they prefer a smaller, sooner payoff or a larger, later payoff. They decide they will wait for the larger, later payoff. Time passes until the smaller pay-off becomes immediately available. They change their mind and take the smaller payoff.

Why did the agent initially choose the larger payoff when they would take the smaller payoff? Were they aware of the likely outcome of their preferences? If they were aware, they might anticipate changing their mind and plan accordingly.

For many of us, we are aware that we make time-inconsistent decisions. We know that we often cave when faced with immediate temptation. Even if we don’t plan to eat a whole packet of cookies for dinner, have more than one beer, or stay up late watching just one more episode, we often do.

26.2 Naïve and sophisticated present-biased agents

To bring the idea that we are aware of our present bias into the analysis, I will distinguish between two types of present-biased agents: naive and sophisticated.

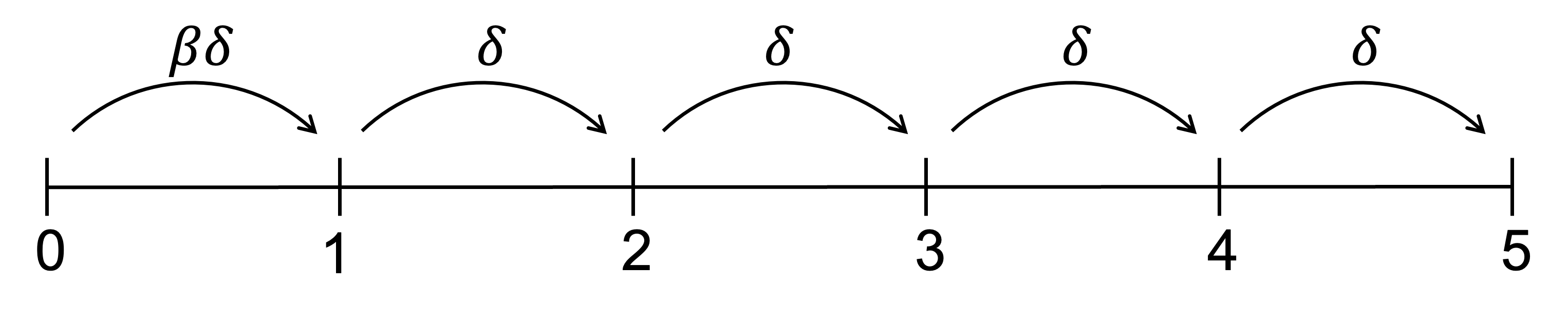

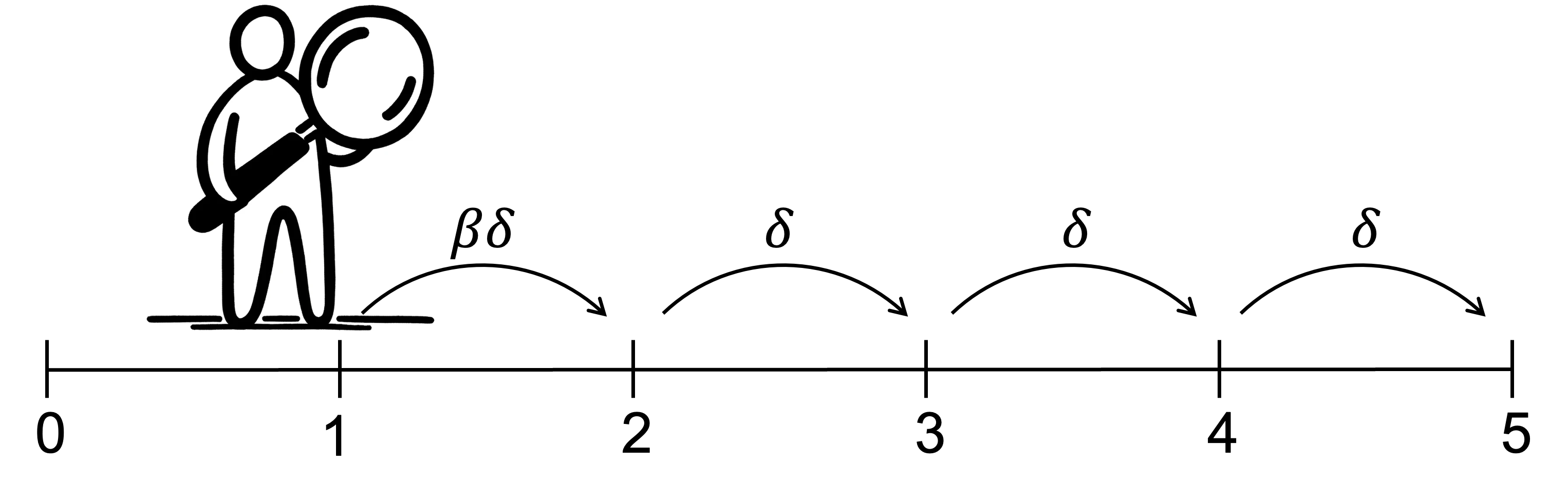

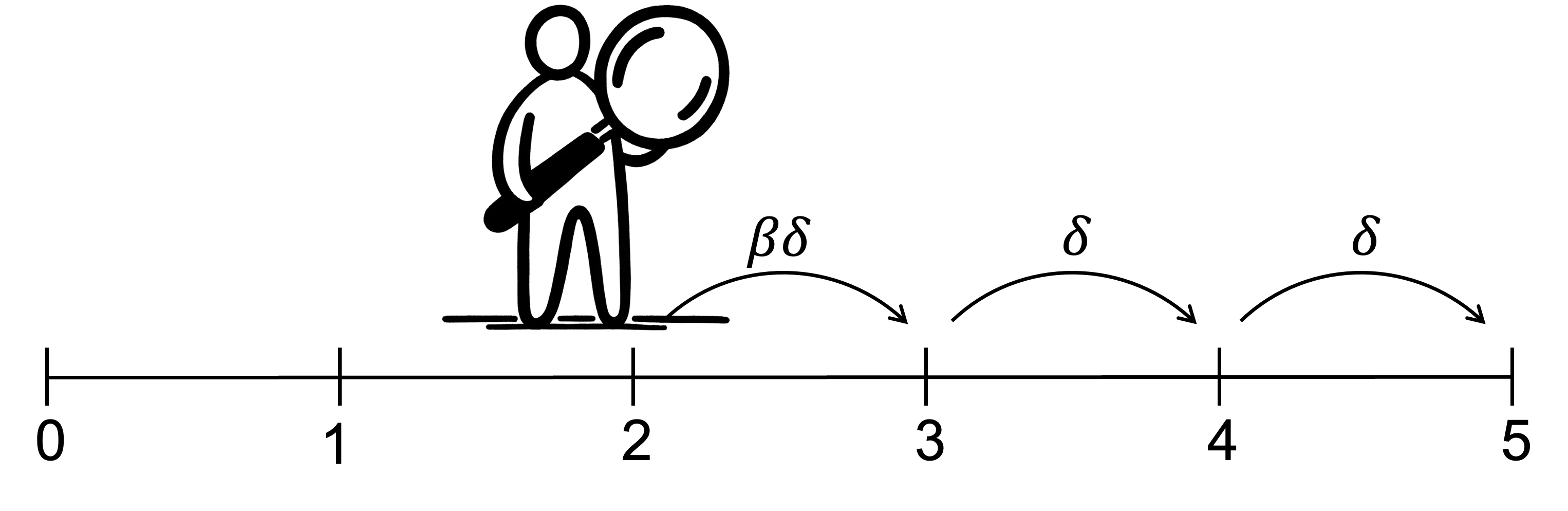

Consider how a present-biased agent discounts a payoff for each successive period of delay under the \beta\delta model. The first period of delay results in the application of a total discount factor of \beta\delta. Each additional period of delay results in the application of an additional discount factor of \delta. The discount factor applied for the first period of delay is relatively smaller - or the magnitude of the discount relatively greater - than the additional discount applied for any additional period of delay.

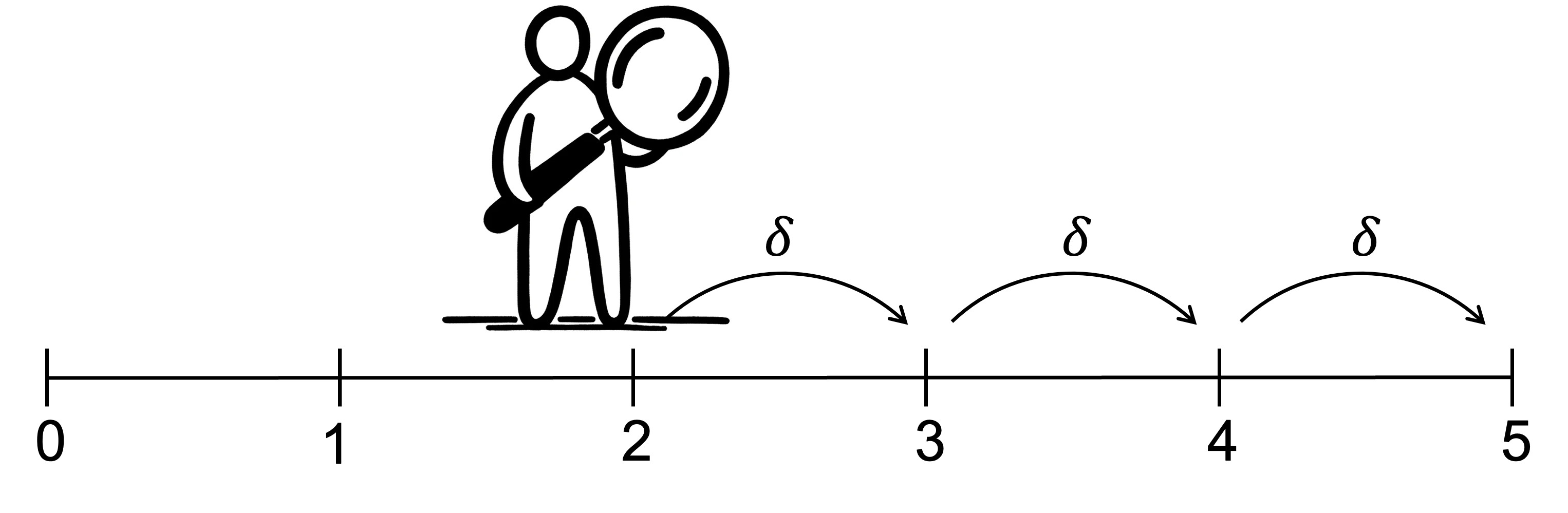

A naive present-biased agent believes that the relative difference in discount between periods that they can see today will persist as time passes. That is, they believe that the discount factor of \delta applied between, say, periods 2 and 3, will still be the relative discount when they reach period 2.

However, when period 2 does arrive, the outcome in period 3 will be discounted by both the short-term discount factor \beta and the usual discount factor \delta, compared to no discount for the outcome in period 2. As a result, the relative discount of outcomes at different times will change when one of those outcomes becomes due today.

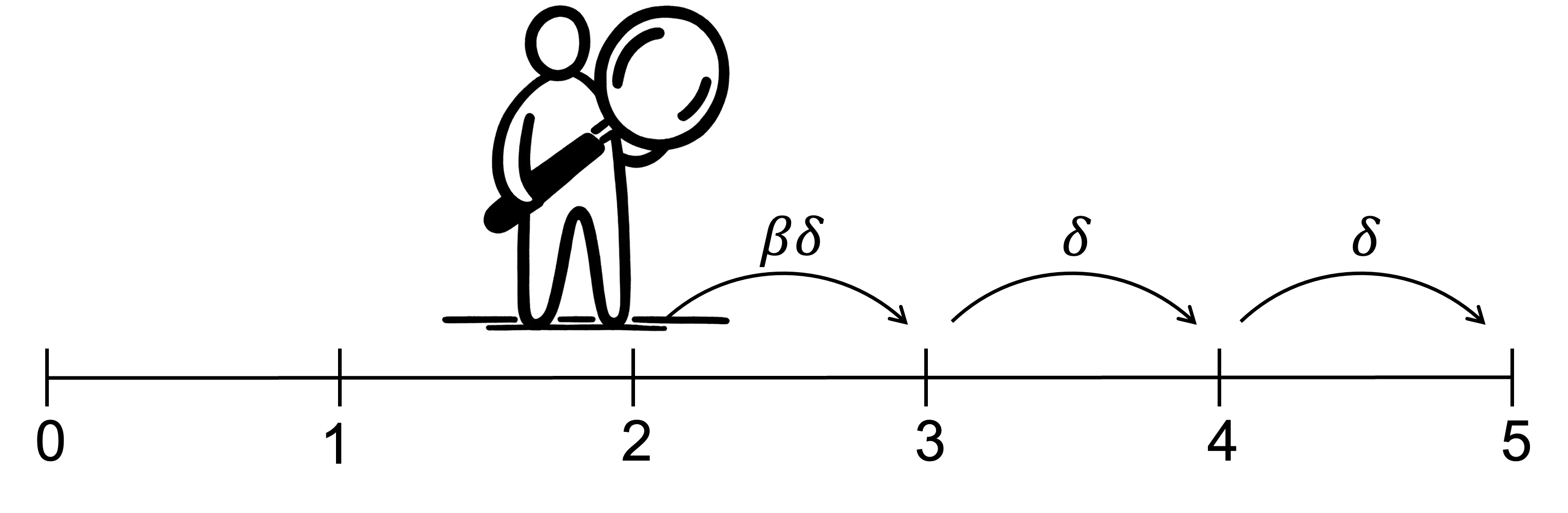

A sophisticated present-biased agent correctly believes that they will apply both the short-term and usual discount factors in the future. As a result, they understand that the relative discount of different outcomes will change when one of those outcomes becomes due today. They understand that if faced with the temptation to take benefits or to delay costs, they will do so.

A sophisticated and naive person can make different decisions despite having the same level of impatience, \delta, and the same level of present bias, \beta. Any difference emerges in the way that they reason through an intertemporal choice.

The naive agent makes their plans by forward reasoning, starting from today.

- First, they decide their preferred option for today, period 0, believing that they will stick to their plan in the future.

- When they move to the next period they recompute their plan, again believing they will stick to the plan once they move to the next period.

- They repeat this process as they move through time.

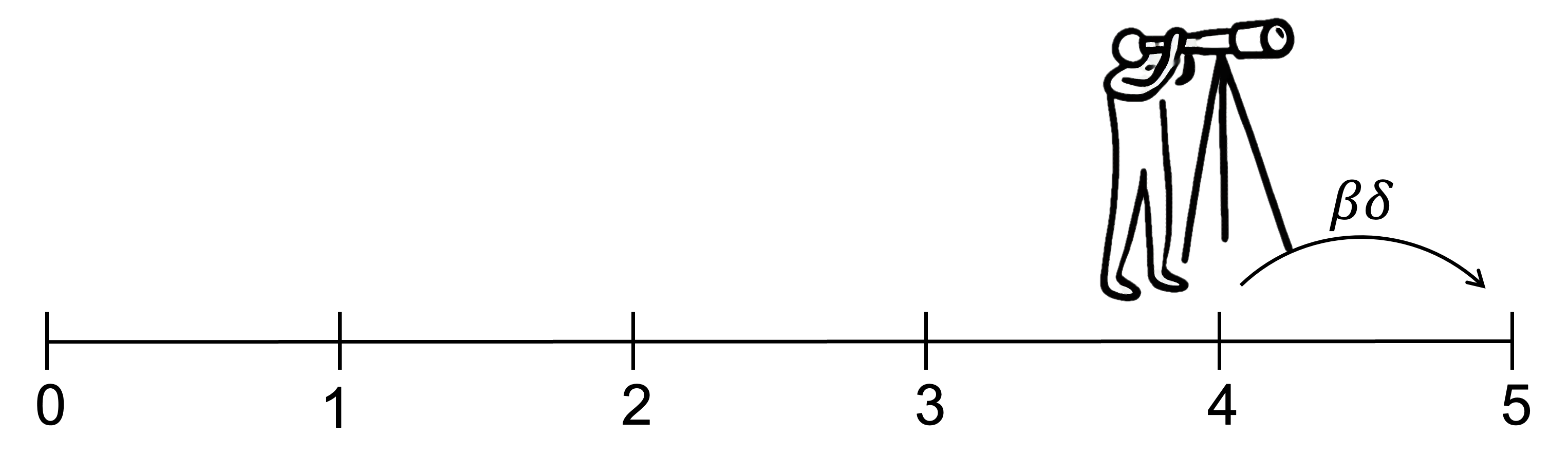

In contrast, the sophisticated present-biased agent makes their plans by backward reasoning, starting from the final period.

- For that final period, they solve for the preferred action.

- They then consider one period earlier and solve for the preferred action, accounting for the previous decision. This means, that if they calculate that they will cave into temptation at a certain time, they will remove the option to resist from their choice set. Absent the ability to commit to an action, they will resign themselves to giving into temptation in advance.

- They repeat this process as they move back to today.

26.3 Examples

The difference between naive and sophisticated present-biased agents is best illustrated through examples.

26.3.1 $100 next week or $110 in two weeks

For the first example, suppose we have a naive and a sophisticated present-biased agent, each with \beta=0.95, \delta=0.95 and utility each period of u(x_n)=x_n.

We offer them both the following choice.

Would you like $100 next week or $110 in two weeks?

We also tell them that we will allow them to reconsider their decision next week.

When the naive present-biased agent considers this problem, they simply compare the discounted utility of each payoff from the perspective of today.

The discounted utility of the $100 next week is:

\begin{align*} U_0(1,\$100)&=\beta u(x_1) \\[6pt] &=\beta\delta u(\$100) \\[6pt] &=0.95\times 0.95\times 100 \\[6pt] &=90.25 \end{align*}The discounted utility of the $110 in two weeks is:

\begin{align*} U_0(2,\$110)&=\beta\delta^2 u(x_2) \\[6pt] &=\beta\delta^2 u(\$110) \\[6pt] &=0.95\times 0.95^2\times 110 \\[6pt] &=94.31 \end{align*}As U_0(1,\$100)=90.25<94.31=U_0(2,\$110), at t=0 the present-biased agent will prefer to receive $110 in two weeks.

But this choice does accord with the naive agent’s preferences next week. Next week (at t=1) they will calculate utility of the $100 as:

\begin{align*} U_1(1,\$100)&=u(x_1) \\[6pt] &=u(\$100)\\[6pt] &=100 \end{align*}The discounted utility of the $110 a week later is:

\begin{align*} U_1(2,\$110)&=\beta\delta u(x_2) \\[6pt] &=\beta\delta u(\$110) \\[6pt] &=0.95\times 0.95\times 110 \\[6pt] &=99.275 \end{align*}As U_1(1,\$100) > U_1(2,\$110), the present-biased agent will prefer to receive $100 immediately.

At t=0 their preference is inconsistent with what it will be next week at t=1.

The sophisticated present-biased agent will approach this decision differently. They consider it using backward induction.

First, they will look at the choice they will face next week and calculate the discounted utility of each option as they will calculate it at that time.

That is, they calculate the discounted utility of the $100 at t=1 from the perspective of t=1.

\begin{align*} U_1(1,\$100)&=u(x_1) \\[6pt] &=u(\$100)\\[6pt] &=100 \end{align*}They then calculate the discounted utility of the $110 at t=2 from the perspective of t=1.

\begin{align*} U_1(2,\$110)&=\beta\delta u(x_2) \\[6pt] &=\beta\delta u(\$110) \\[6pt] &=0.95\times 0.95\times 110 \\[6pt] &=99.275 \end{align*}As U_1(1,\$100) > U_1(2,\$110), the sophisticated agent sees that next week, at t=1 they will take the $100.

This is the same pair of calculations that the naive agent made at t=1. The difference is that the sophisticated agent makes this calculation at t=0 from the perspective of t=1. The naive agent does not consider this perspective until t=1.

After considering their preference at t=1, the sophisticated agent then considers their choice at t=0. They see their future decision at t=1 and know that $110 in two weeks is not available to them. The only option they have is to choose $100 in one week. They effectively accept their future present bias now and choose the $100 in one week.

In this example, being naive or sophisticated does not change their final choice. It only changes their beliefs about their final decision over time. The sophisticated agent knows at t=0 what they will do at t=1. The naive agent is unaware that at t=1 they will make a decision inconsistent with their choice at t=0. We can summarise their decisions at each time as follows:

| Naive agent | Sophisticated agent | |

|---|---|---|

| t=0 | $110 at t=2 | $100 at t=1 |

| t=1 | $100 at t=1 | $100 at t=1 |

26.3.2 Watching a movie

Suppose we have a naive and a sophisticated present-biased agent, each with \beta=0.5 and \delta=1. They are present-biased, but beyond that present bias demonstrate no impatience.

We offer them the following choice.

An OK movie today (t=0) that gives utility of 6

A good movie next week (t=1) that gives utility of 10

A great movie in two weeks (t=2) that gives utility of 16

We also tell the agents that next week they will be offered an opportunity to change their minds.

First, we consider the naive agent. They calculate utility from the perspective of today.

\begin{align*} U_0(0,\text{OK})&=u(\text{OK}) \\[6pt] &=6 \\ \\ U_0(1,\text{good})&=\beta\delta u(\text{good}) \\[6pt] &=0.5\times 1\times 10 \\[6pt] &=5 \\ \\ U_0(2,\text{great})&=\beta\delta^2 u(\text{great}) \\[6pt] &=0.5\times 1^2\times 16 \\[6pt] &=8 \end{align*}As U_0(2,\text{great})>U_0(0,\text{OK})>U_0(1,\text{good}), the naive agent will choose the great movie in two weeks.

But what then happens when the naive agent is given the chance to change their mind after one week?

\begin{align*} U_1(1,\text{good})&=u(\text{good}) \\[6pt] &=10 \\ \\ U_1(2,\text{great})&=\beta\delta u(\text{great}) \\[6pt] &=0.5\times 1\times 16 \\[6pt] &=8 \end{align*}As U_1(1,\text{good})>U_1(2,\text{great}), the naive agent will change their mind and watch the good movie immediately.

What of our sophisticated agent?

They will make their decision today based on correct beliefs about their future preferences. To do this, they solve by backward induction. First, what will their decision be next week?

\begin{align*} U_1(1,\text{good})&=u(\text{good}) \\[6pt] &=10 \\ \\ U_1(2,\text{great})&=\beta\delta u(\text{great}) \\[6pt] &=0.5\times 1\times 16 \\[6pt] &=8 \end{align*}As U_1(1,\text{good})>U_1(2,\text{great}), the sophisticated agent can see that they will choose to watch the good movie immediately.

Knowing this is the case, the sophisticated agent now decides whether they prefer the OK movie today or the good movie next week.

\begin{align*} U_0(0,\text{OK})&=u(\text{OK}) \\[6pt] &=6 \\ \\ U_0(1,\text{good})&=\beta\delta u(\text{good}) \\[6pt] &=0.5\times 1\times 10 \\[6pt] &=5 \\ \end{align*}As U_0(0,\text{OK})>U_0(1,\text{good}), the sophisticated agent prefers the OK movie today.

From today’s perspective, the sophisticated agent would prefer the great movie in two weeks, but as they know they will cave in to their present bias next week and watch the good movie, they make today’s decision on that basis. They know that if they select the great movie today they won’t watch it.

26.3.3 A library fine

A naive present-biased agent has failed to return their library books and is fined at t=0. They can select one of the following payment schemes:

(0,-\$10), (1,-\$15) or (2,-\$25)

That is, they can pay $10 today, $15 at t=1 or $25 at t=2.

They are free to change the scheme over time as they see fit.

The agent’s utility is linear in money - that is, u(x_n)=x_n - with discount factors \beta=0.5 and \delta=1.

The naive agent calculates the utility of each option today.

\begin{align*} U_0(0,-\$10)&=u(-\$10) \\[6pt] &=-10 \\ \\ U_0(1,-\$15)&=\beta\delta u(-\$15) \\[6pt] &=0.5\times 1\times (-15) \\[6pt] &=-7.5 \\ \\ U_0(2,-\$25)&=\beta\delta^2 u(-\$25) \\[6pt] &=0.5\times 1^2\times (-25) \\[6pt] &=-12.5 \end{align*}As U_0(1,-\$15)>U_0(0,-\$10)>U_0(2,-\$25), the naive agent will choose to pay $15 at t=1.

A week passes and the naive agent is now at t=1, the time when they were planning to pay the fine. The naive agent reconsiders their decision.

\begin{align*} U_1(1,-\$15)&=u(-\$15) \\[6pt] &=-15 \\ \\ U_1(2,-\$25)&=\beta\delta u(-\$25) \\[6pt] &=0.5\times 1\times (-25) \\[6pt] &=-12.5 \end{align*}As U_1(2,-\$25)=-12.5>=-15=U_1(1,-\$15), the naive agent changes their decision and further delays their payment. They now choose to pay $25 at t=2.

When they reach t=2, they have no choice but to pay the $25.

A sophisticated present-biased agent has also failed to return their library books and is fined at t=0. They can select one of the following payment schemes:

(0,-\$10), (1,-\$15) or (2,-\$25)

They are free to change the scheme over time as they see fit.

The sophisticated agent’s utility is linear in money u(x_n)=x_n, with discount factors \beta=0.5 and \delta=1.

For the sophisticated agent, we start calculating utility from the final period.

At t=2, they have no choice but to pay the $25.

What of t=1?

\begin{align*} U_1(1,-\$15)&=u(-\$15) \\[6pt] &=-15 \\ \\ U_1(2,-\$25)&=\beta\delta u(-\$25) \\[6pt] &=0.5\times 1\times (-25) \\[6pt] &=-12.5 \end{align*}The sophisticated agent can see that if they choose at t=1, they will choose to pay $25 at t=2.

Now we iterate at t=0. The sophisticated agent only compares $10 at t=0 with $25 at t=2 because they know that at t=1 they will select $25 at t=2. They know that if they delay once they will delay again and end up paying the largest fine. Hence they limit their comparison to those outcomes that might occur:

\begin{align*} U_0(0,-\$10)&=u(-\$10) \\[6pt] &=-10 \\ \\ U_0(2,-\$25)&=\beta\delta^2 u(-\$25) \\[6pt] &=0.5\times 1^2\times (-25) \\[6pt] &=-12.5 \end{align*}As U_0(0,-\$10)>U_0(2,-\$25), the sophisticated agent will choose to pay $10 at t=0.

In the examples, we have seen two contrasting outcomes for the sophisticated agent.

In the movie example, they watch an OK movie today, rather than a good movie in one week or a great movie in two, because they knew that they would watch the good movie in one week if they delayed to watch the great movie. As a result, they watched an earlier, worse movie than the naive agent.

In the library fine example, they paid the lowest possible fine as they saw they would further delay paying the fine in the future, leading it to increase even more.

The sophisticated agent’s behaviour arises from two tensions:

They understand that they will not be able to wait for the optimal time.

They are present-biased so they prefer benefits today and costs delayed to the future.

In combination, these imply a sophisticated agent will generally take action earlier than the naive agent. They can “prepoperate”, which is doing something now when it would be better to wait.