57 Behavioural game theory problems

57.1 Airline competition

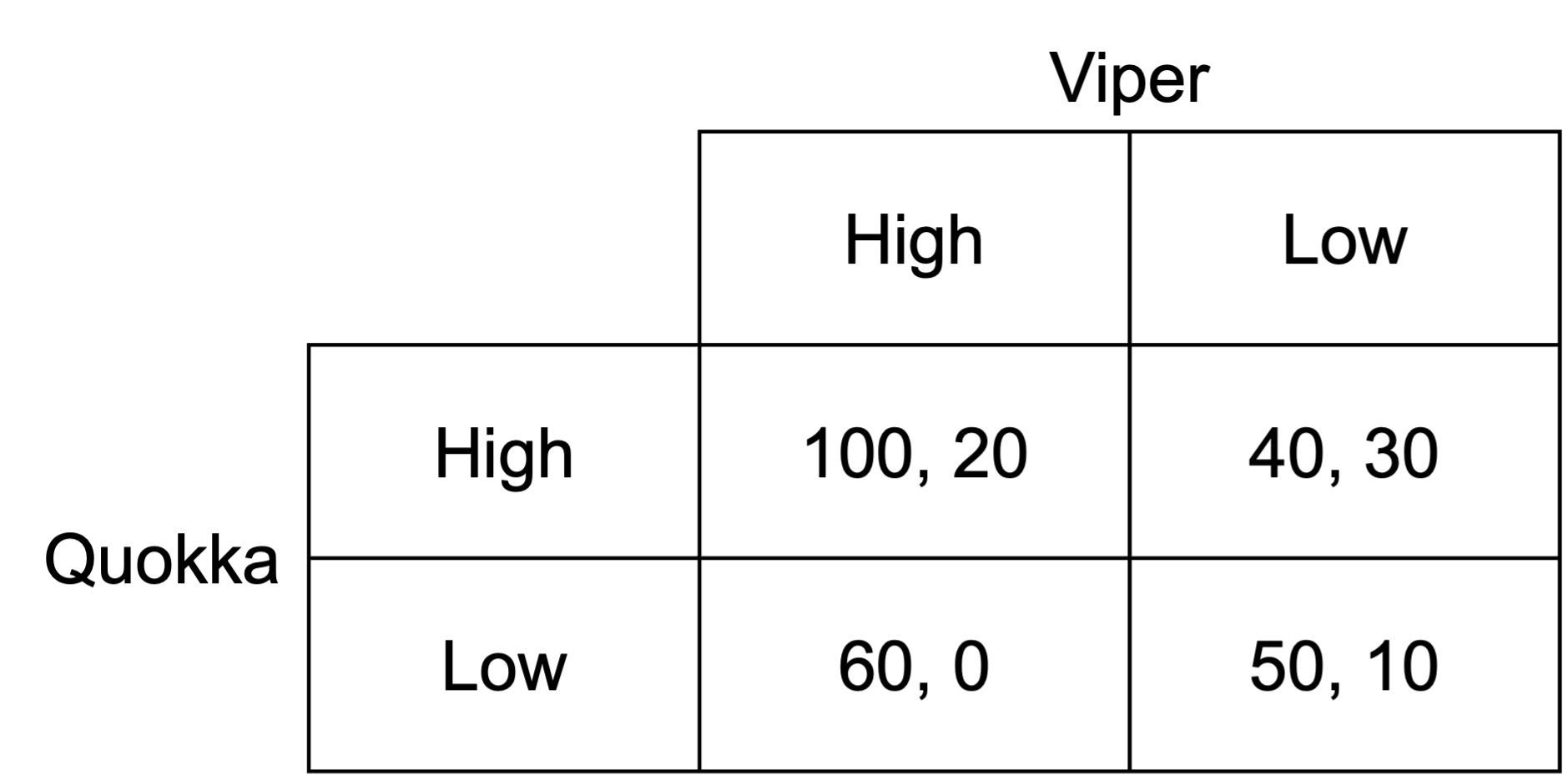

Quokka Airlines and Viper Air are competitor airlines. Each is considering how it should price its tickets. They have two options: a high price or a low price. Each must choose the price simultaneously.

If one airline offers a lower price than the other, they gain more market share but a lower profit margin. If both airlines offer the same price, Quokka takes more of the market as the incumbent airline.

The expected payoffs for each combination of actions are as follows, with the payoff (x,y) being the payoffs for Quokka and Viper respectively.

a) Are there any pure-strategy Nash equilibria? If so, what are they?

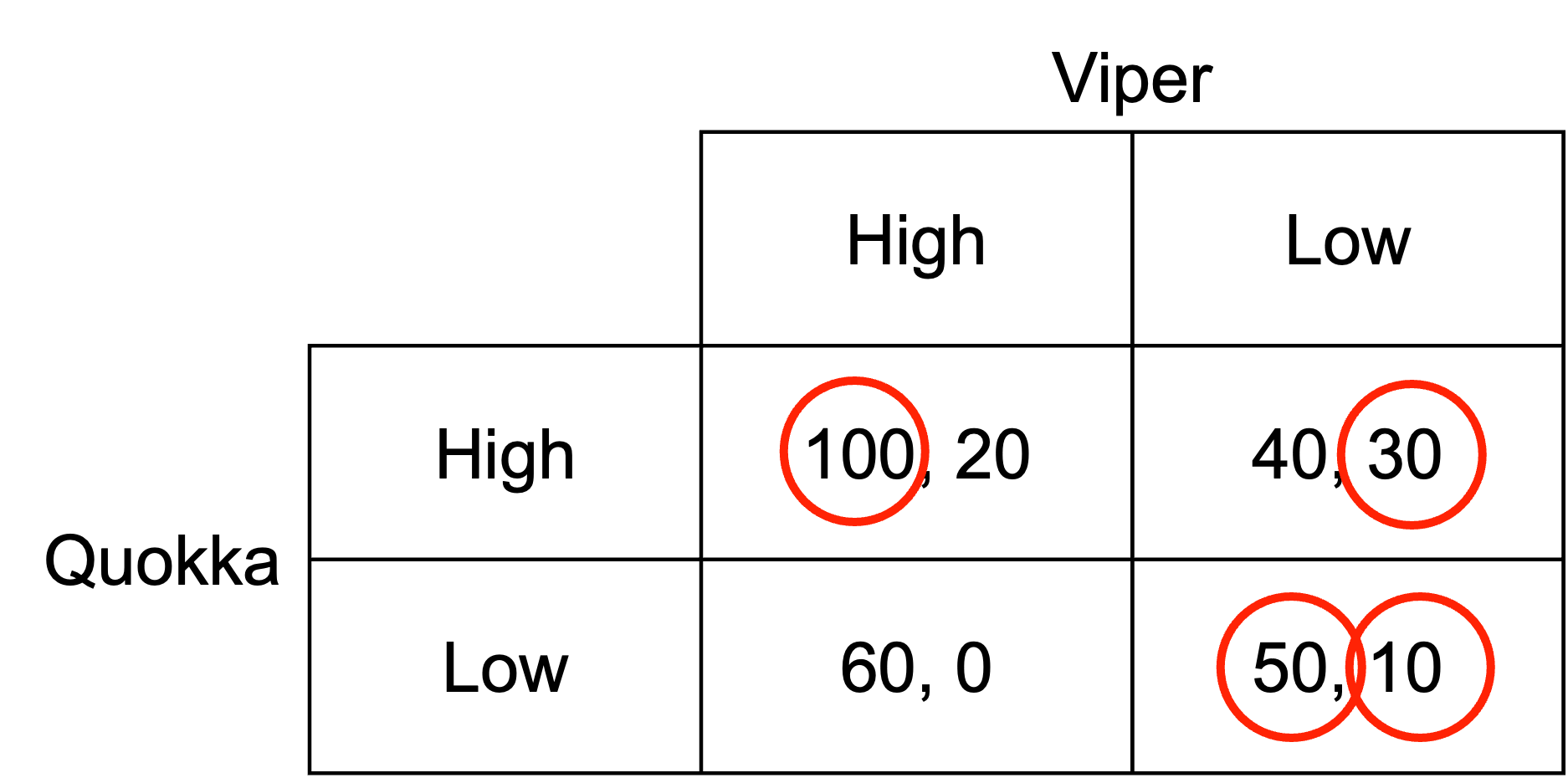

We determine the pure-strategy Nash equilibria by considering the best response of each player to each of the other player’s strategies.

If Viper sets prices high, Quokka can choose high for a payoff of 100 or low for a payoff of 60. High is the best response.

If Viper sets prices low, Quokka can choose high for a payoff of 40 or low for a payoff of 50. Low is the best response.

If Quokka sets prices high, Viper can choose high for a payoff of 20 or low for a payoff of 30. Low is the best response.

If Quokka sets prices low, Viper can choose high for a payoff of 0 or low for a payoff of 10. Low is the best response.

The pure Nash equilibrium is therefore (low, low). Neither has an incentive to deviate.

b) Suppose the managers of Quokka and Viper are level-k thinkers.

If they were level-0, both would choose high or low with equal probability.

What would each player do if they were a level-1 thinker?

A level-1 thinker assumes that the other player is a level-0 thinker. Each level-1 thinker plays the optimal strategy on this assumption.

A level-1 Quokka plays the optimal strategy against a level-0 Viper. A level-0 Viper plays high or low with equal probability. The payoffs to Quokka from each option are:

\begin{align*} U_Q(\text{high})&=0.5\times 100+0.5\times 40 \\ &=70 \end{align*} \begin{align*} U_Q(\text{low})&=0.5\times 60+0.5\times 50 \\ &=55 \end{align*}

Quokka chooses high.

The payoffs to Viper from each option are:

\begin{align*} U_V(\text{high})&=0.5\times 20+0.5\times 0 \\ &=10 \end{align*} \begin{align*} U_V(\text{low})&=0.5\times 30+0.5\times 10 \\ &=20 \end{align*}

Viper chooses low.

c) What would each player do if they were a level-2 thinker?

A level-2 thinker assumes that the other player is a level-1 thinker. Each level-2 thinker plays the optimal strategy on this assumption.

A level-2 Quokka knows that the level-1 Viper will choose low. Therefore, the payoff from high is 40 and from low is 50. Quokka chooses low.

A level-2 Viper knows that the level-1 Quokka will choose high. Therefore, the payoff from high is 20 and from low is 30. Viper chooses low.

d) What would each player do if they were a level-3 or above thinker?

At whatever level of thinking the players discover the Nash equilibrium, for any higher level of thinking they will remain at the Nash equilibrium.

Therefore, at level-3 and above, both players will choose low.

e) Suppose now that the managers of Quokka and Viper are perfectly rational. Each is considering how they could make more profit.

A staff member in Viper suggests launching an advertising campaign with high prices before they and Quokka choose. Once Viper has advertised their prices, they will be constrained to setting them high.

Is this a good idea? What concept does this illustrate?

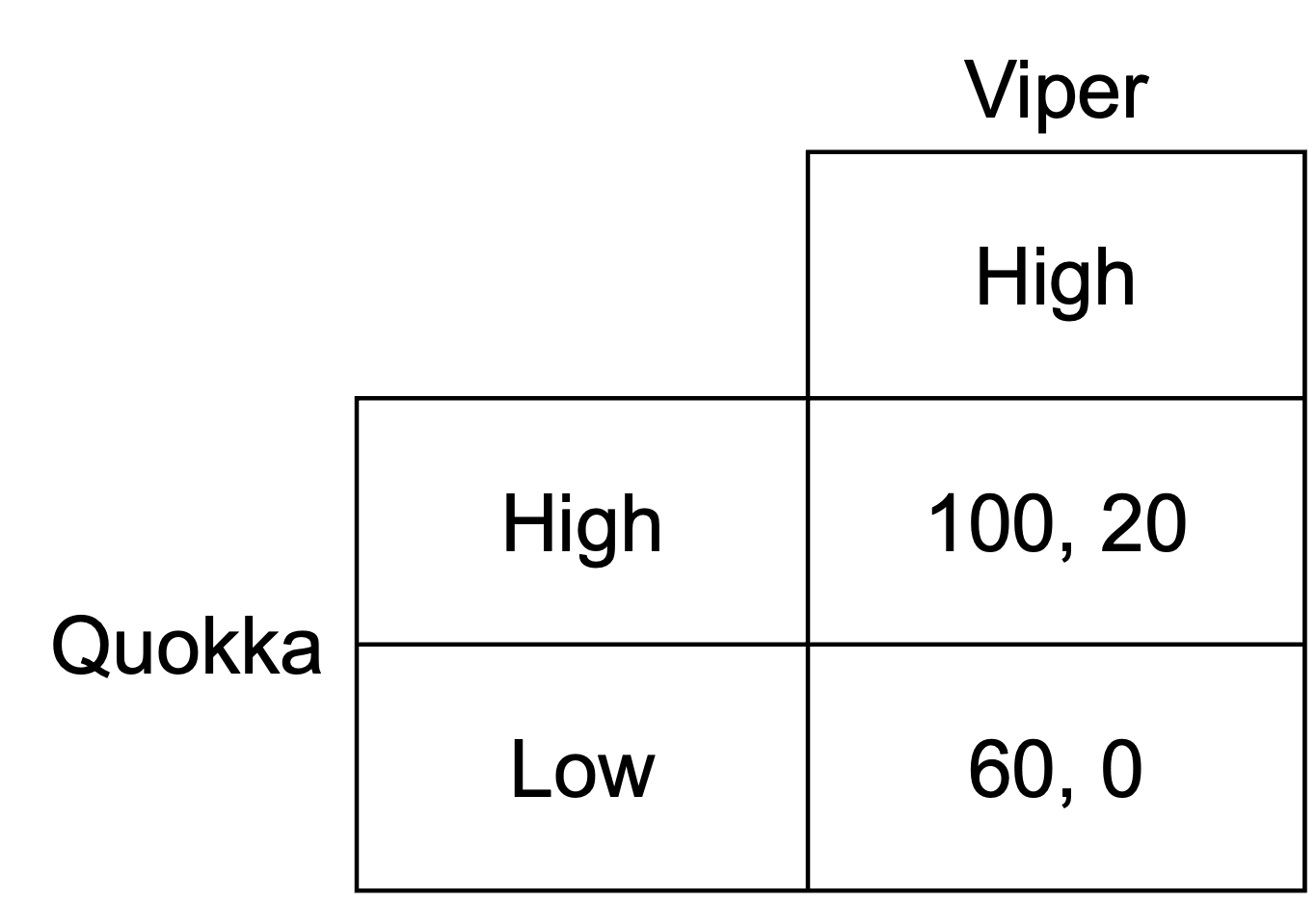

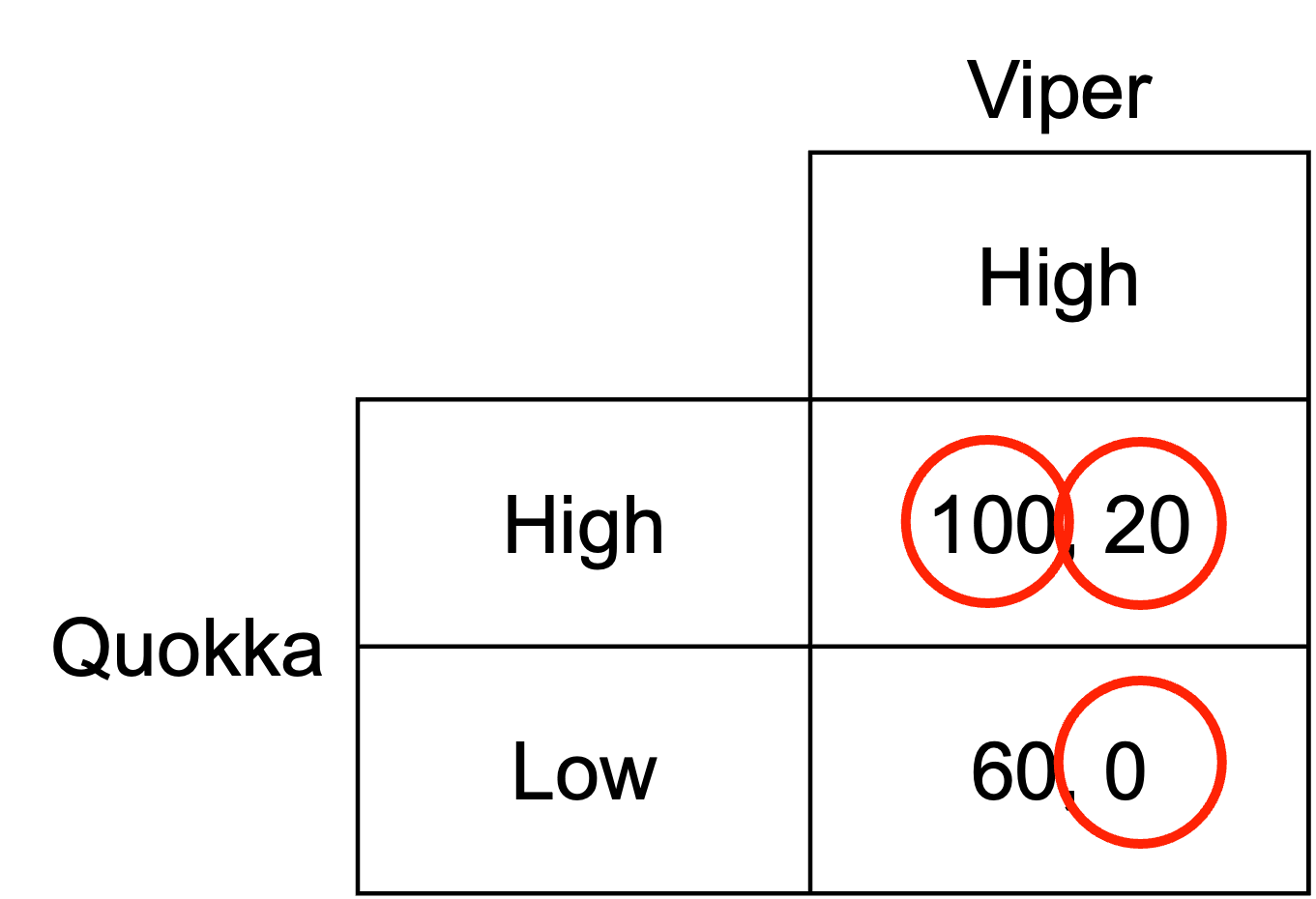

Suppose Viper advertises high prices and is committed to that choice. The game therefore becomes:

With this game, Viper plays high no matter what choice is made by Quokka. They effectively have no choice.

Quokka can choose high for a payoff of 100 or low for a payoff of 60. High is the best response.

The new Nash equilibrium is (high, high). Viper has increased its payoff from 10 to 20 by making the strategic move. The move is therefore a good idea.

This example illustrates the concept of commitment via a strategic move.

57.2 Valuing a business

You are considering buying a small business. You research the business, attempting to estimate the revenue and profit it will generate. Based on your research, you determine a fair valuation is $850,000.

The business ultimately sells for $1.1 million to another person. You discover that many other parties were interested in buying the business.

You later hear that the purchaser is disappointed with the business and that it is worth less than they paid. What phenomenon could this be an example of? Explain.

This is an example of the winner’s curse.

The winner’s curse occurs when the winner of an auction is the bidder who most overestimates the value of the item. The winner therefore pays more than the item is worth.

57.3 Cafe

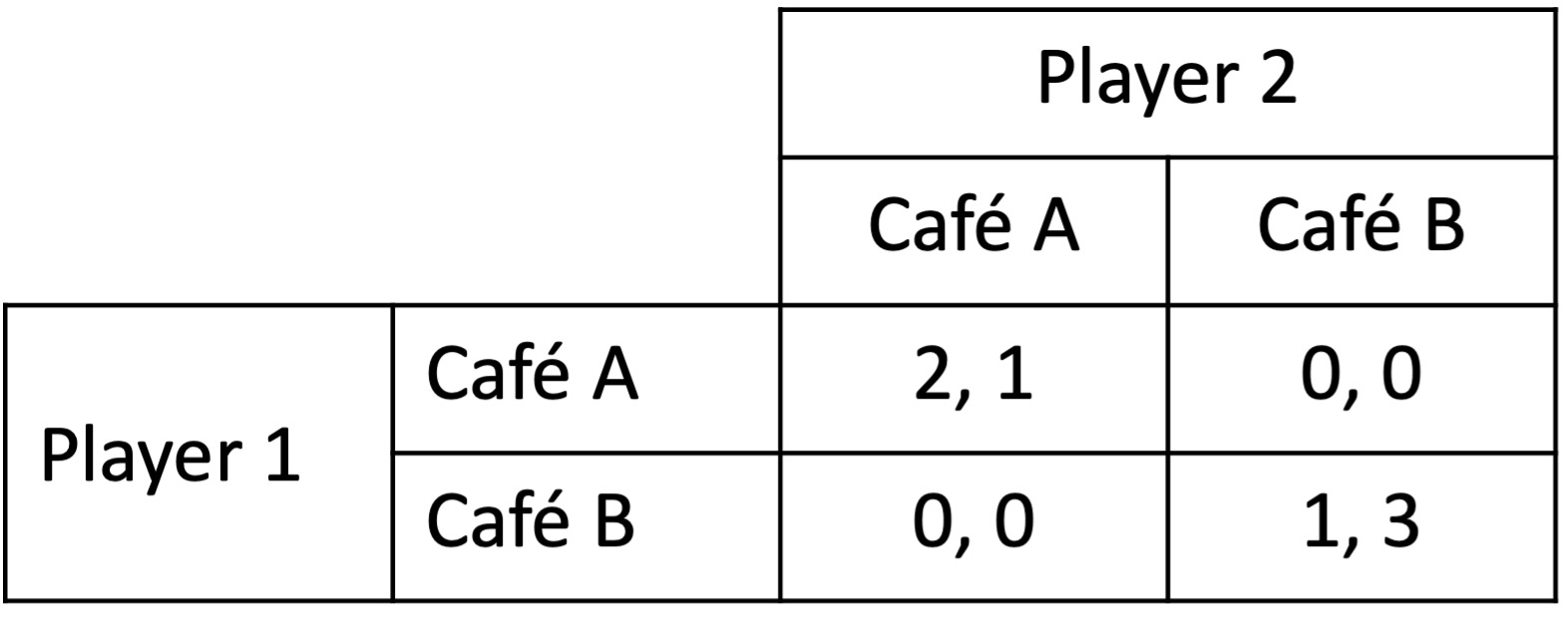

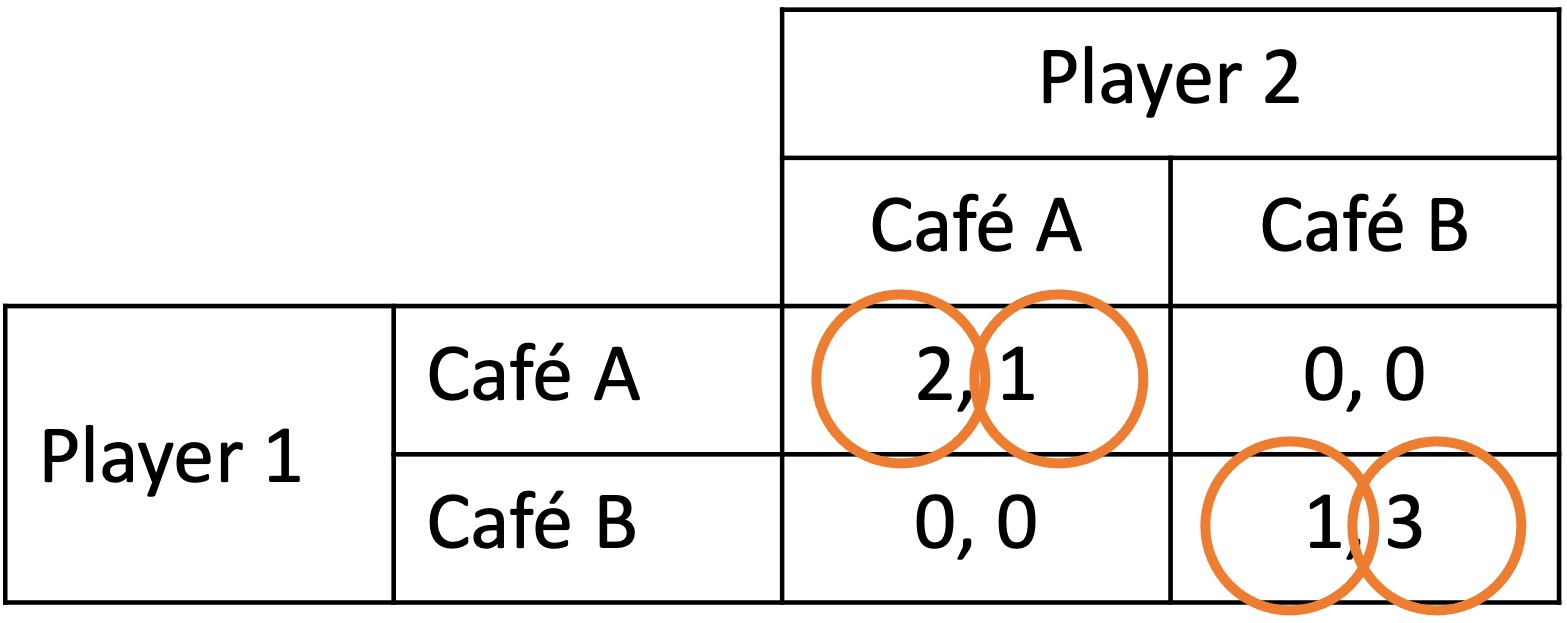

Two friends, Player 1 and Player 2, have arranged to meet at a cafe. Neither can remember which of the two cafes in town they had arranged to meet at.

Each player has a favourite cafe. However, they would prefer to go to their less-favourite cafe with a friend than go to their favourite cafe alone.

Each chooses a cafe and goes there. The payoffs for each combination of choices are in the table below, with the payoffs (x, y) being the payoffs for Player 1 and Player 2 respectively.

a) What are the pure-strategy Nash equilbria of this game?

If player 2 chooses cafe A, player 1 wants to choose cafe A.

If player 2 chooses cafe B, player 1 wants to choose cafe B.

If player 1 chooses cafe A, player 1 wants to choose cafe A.

If player 1 chooses cafe B, player 1 wants to choose cafe B.

The two pure-strategy Nash equilibria are (cafe A, cafe A) and (cafe B, cafe B).

b) What would Player 1 and Player 2 do if each was a level-1 thinker? Explain.

If Player 2 chooses randomly, Player 1’s payoff’s from each option are:

\begin{align*} U_1(\text{cafe A})&=0.5\times 2+0.5\times 0=1 \\[6pt] U_1(\text{cafe B})&=0.5\times 0+0.5\times 1=0.5 \end{align*}

Player 1 chooses cafe A.

If Player 1 chooses randomly, Player 2’s payoff’s from each option are:

\begin{align*} U_2(\text{cafe A})&=0.5\times 1+0.5\times 0=0.5 \\[6pt] U_2(\text{cafe B})&=0.5\times 0+0.5\times 3=1.5 \end{align*}

Player 2 chooses cafe B.

c) What would Player 1 and Player 2 do if each was a level-2 thinker? Explain.

The level-2 Player 1 assumes that Player 2 is level-1. Therefore, they assume that Player 2 will choose cafe B. Accordingly, they choose cafe B.

The level-2 Player 2 assumes that Player 1 is level-1. Therefore, they assume that Player 1 will choose cafe A. Accordingly, they choose cafe A.

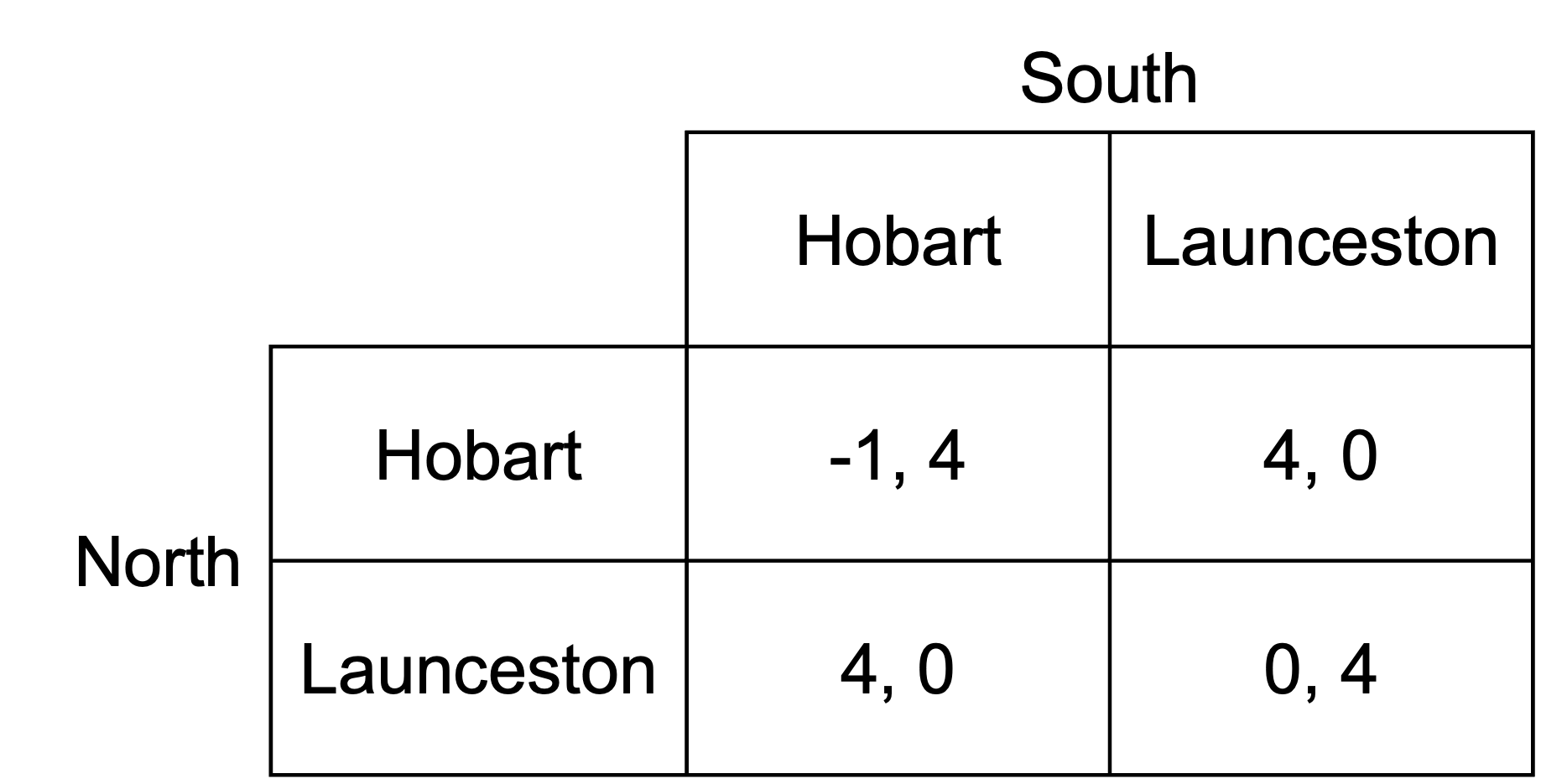

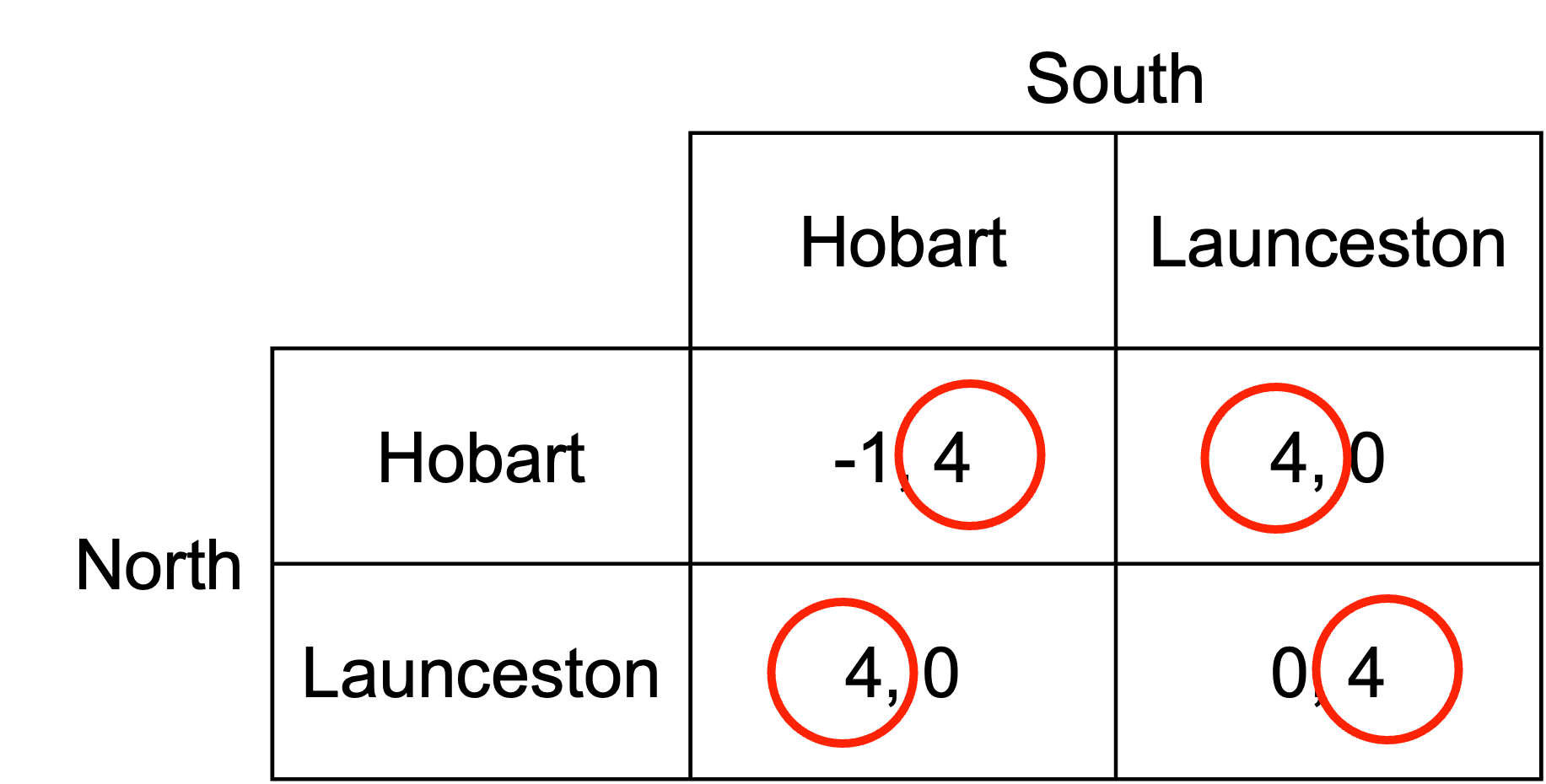

57.4 A military attack

An army from the North is about to attack the South.

The North can attack one of two cities: Hobart or Launceston. Launceston is easier to attack as it is closer.

The South needs to decide which city it will plan to defend.

If the North attacks an undefended city, it will win. The South can repel any attack on a city it has chosen to defend.

The expected payoffs for each combination of actions are as follows, with the payoff (x,y) being the payoffs for the North and South respectively.

a) Are there any pure-strategy Nash equilibria? If so, what are they?

We determine the pure-strategy Nash equilibria by considering the best response of each player to each of the other player’s strategies.

If the South defends Hobart, North can choose Hobart for a payoff of -1 or Launceston for a payoff of 4. Launceston is the best response.

If the South defends Launceston, North can choose Hobart for a payoff of 4 or Launceston for a payoff of 0. Hobart is the best response.

If the North attacks Hobart, South can defend Hobart for a payoff of 4 or Launceston for a payoff of 0. Hobart is the best response.

If the North attacks Launceston, South can defend Hobart for a payoff of 0 or Launceston for a payoff of 4. Launceston is the best response.

There is no pure-strategy Nash equilibrium. For any combination of choices, one of the armies has an incentive to change their choice.

b) Suppose the commanders of the North and South are level-k thinkers.

If they were level-0, both would choose Hobart or Launceston with equal probability.

What would each player do if they were a level-1 thinker?

A level-1 thinker assumes that the other player is a level-0 thinker. Each level-1 thinker plays the optimal strategy on this assumption.

A level-1 North plays the optimal strategy against a level-0 South. A level-0 South plays Hobart or Launceston with equal probability. The payoffs to North from each option are:

\begin{align*} U_N(\text{Hobart})=0.5\times -1+0.5\times 4=1.5 \\ \\ U_N(\text{Launceston})=0.5\times 4+0.5\times 0=2 \end{align*}

North attacks Launceston.

\begin{align*} U_S(\text{Hobart})=0.5\times 4+0.5\times 0=2 \\ \\ U_S(\text{Launceston})=0.5\times 4+0.5\times 0=2 \end{align*}

South is indifferent between defending Hobart and Launceston. They can choose either.

c) What would each player do if they were a level-2 thinker?

A level-2 thinker assumes that the other player is a level-1 thinker. Each level-2 thinker plays the optimal strategy on this assumption.

A level-2 North knows that the level-1 South is indifferent between defending Hobart and Launceston. If North assumes that South will defend each with equal probability, the payoffs to North from each option are:

\begin{align*} U_N(\text{Hobart})=0.5\times -1+0.5\times 4=1.5 \\ \\ U_N(\text{Launceston})=0.5\times 4+0.5\times 0=2 \end{align*}

North attacks Launceston.

A level-2 South knows that the level-1 North attacks Launceston. The South defends Launceston for payoff of 4 (rather than Hobart for payoff of 0).

57.5 Acquiring a company

The following example draws on Bazerman and Moore (2013).

Company A is considering acquiring Company T.

The value of Company T depends on the outcome of an oil exploration project. If the project fails, the company under current management will be worth nothing ($0 per share). If the project succeeds, the value of the company under current management could be as high as $100 per share. All values between $0 and $100 are equally likely.

Company T will be worth 50 per cent more in the hands of Company A than under current management. If the project fails, the company will be worth $0 per share under either management. If the exploration project generates a $50 per share value under current management, the value under Company A will be $75 per share. And so on.

Company A is considering what price per share they should offer. This offer must be made before Company A knows the outcome of the drilling project, but after Company T learns the result. Company T will accept any offer from Company A if it is profitable for them.

a) Show that for any offer above zero Company A expects to lose money.

If Company A offers \$x, Company T will accept x% of the time, whenever the firm is worth between $0 and \$x. Since all those values are equally likely, the firm will be worth on average \$x/2 to company T when they accept. The shares will therefore be worth 1.5\times x/2=3x/4 on average for company A. That gives Company A profit of:

\begin{align*} \pi_A&=\frac{3x}{4}-x \\[6pt] &=-\frac{x}{4} \end{align*}

Any offer above $0 generates a negative expected return, a loss of 25% of the offer.

To give an example, if Company A offered $60, it will be accepted 60% of the time - whenever the firm is worth between $0 and $60 for company T. Since all those values are equally likely, the firm will be worth on average $30 to company T when they accept, meaning it will be worth $45 on average for company A. A $60 offer will result in an average loss of $15.

b) People given this problem tend to bid between $50 and $75 per share (Samuelson and Bazerman (1985)). A typical explanation offered by these people is that the average outcome for Company T is $50, making the value for Company A $75. Any offer in the range between these two values would be agreeable to both parties.

Explain why a “cursed” player representing Company A might make a non-zero offer.

A “cursed” player representing company A does not think that company T’s decision to sell depends on company T’s knowledge of the oil exploration. As a result, they are likely to bid based on their unconditional expected value of the field, not the value conditional on acceptance.

This bidding approach leads to, on average, a loss. The cursed player under-appreciates that company T is more likely to accept when company T’s valuation is low.

57.6 Receiving a faulty product

A customer received a faulty product from a firm and requested a refund as per consumer law. The customer also threatened to complain to the Department of Fair Trading if they did not receive the refund. A customer complaint would be costly to the firm as they would be required to provide a refund in addition to incurring the cost of dealing with the complaint.

The firm offered a store credit instead, believing that the customer would not complain as the time and effort involved would not be worth the potential refund.

However, the customer still complained to the Department of Fair Trading.

a) Use concepts from game theory to explain why the firm might have held that belief.

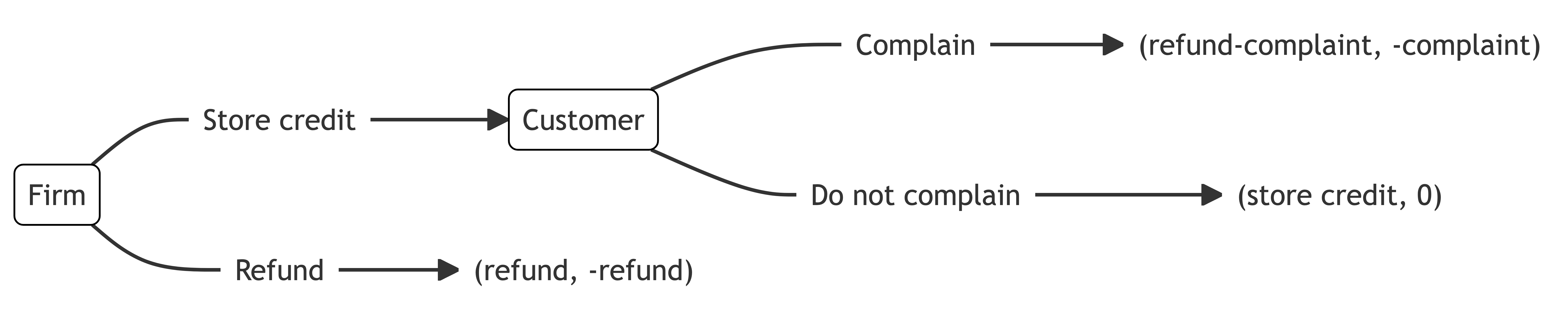

We can draw the extensive form of the game as follows:

We work through this game by backward induction. If the cost to to the customer of complaining is greater than the benefit of obtaining the refund, the customer will not complain. In that case, the firm will offer the store credit.

As the firm believed that the cost to to the customer of complaining is greater than the benefit of obtaining the refund, the customer’s threat to complain would not normally be considered credible.

b) Use concepts from behavioural game theory to explain why the firm’s belief was ultimately incorrect.

The customer’s emotional response may lead them to complain. They might be angry or obtain satisfaction from seeing the firm punished. In that case, the customer will complain even though it is not in their material best interest to do so. Emotionally, it is worthwhile. They incur the cost of complaining but get the benefit of both the refund and the satisfaction from punishing the firm.