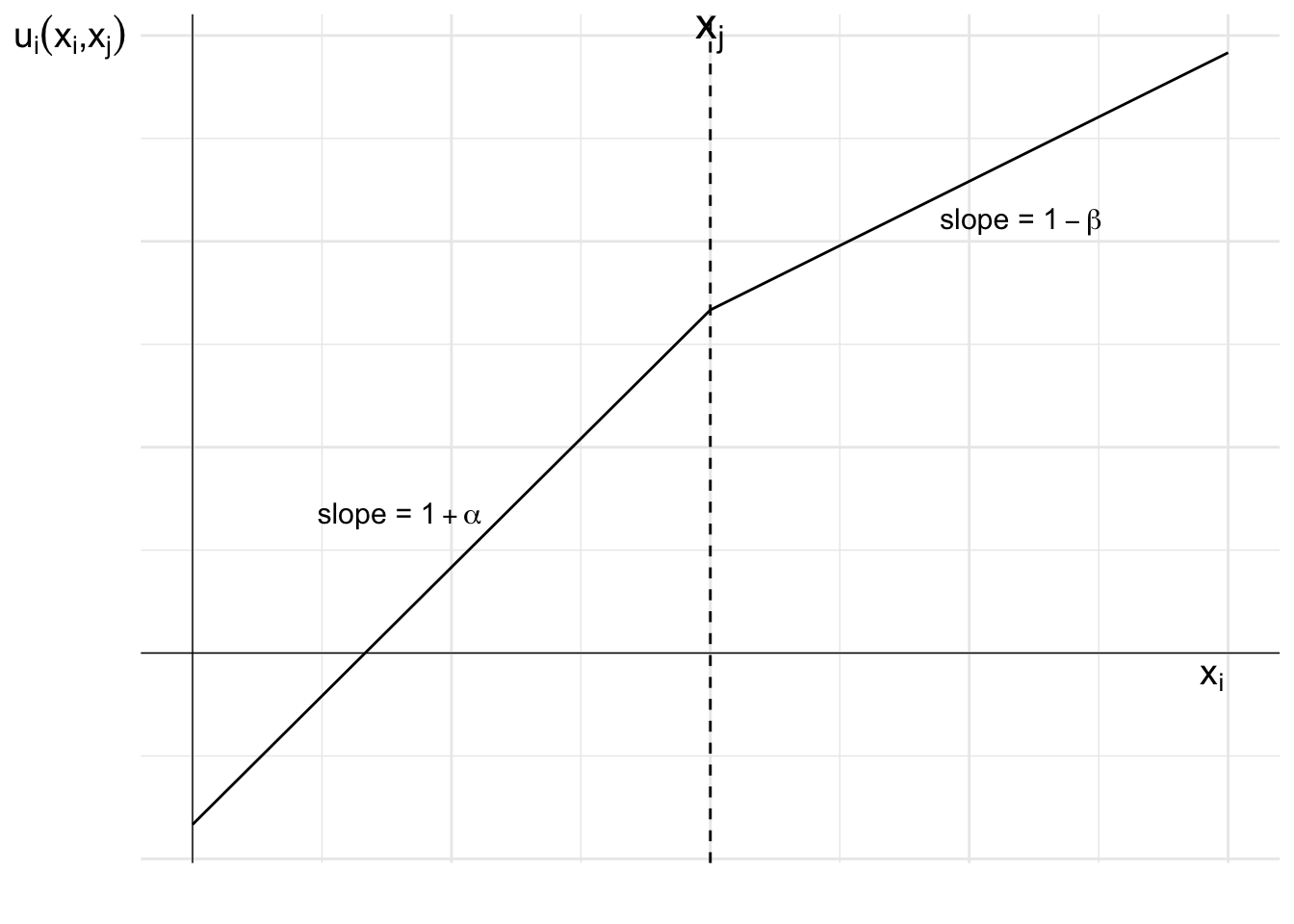

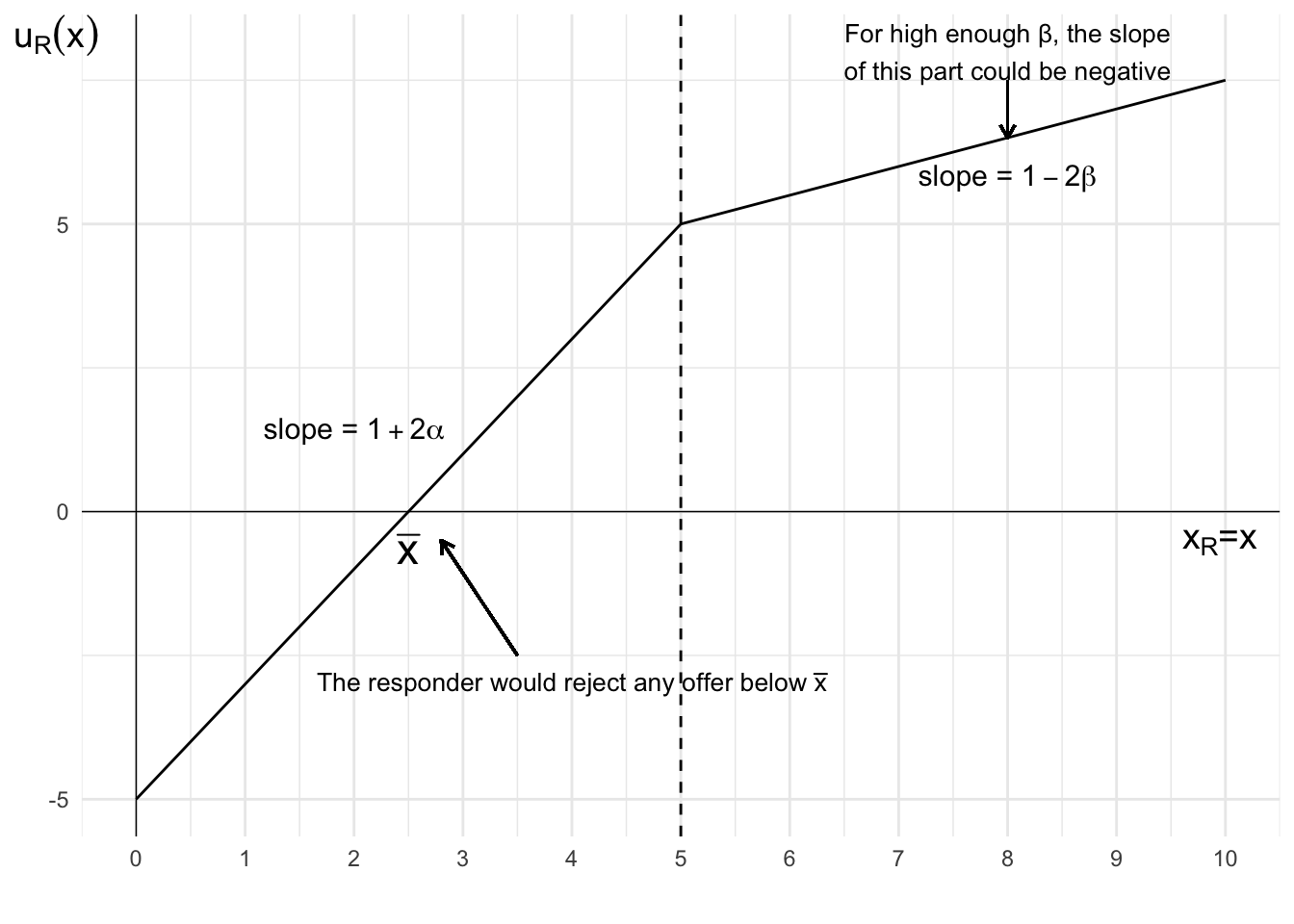

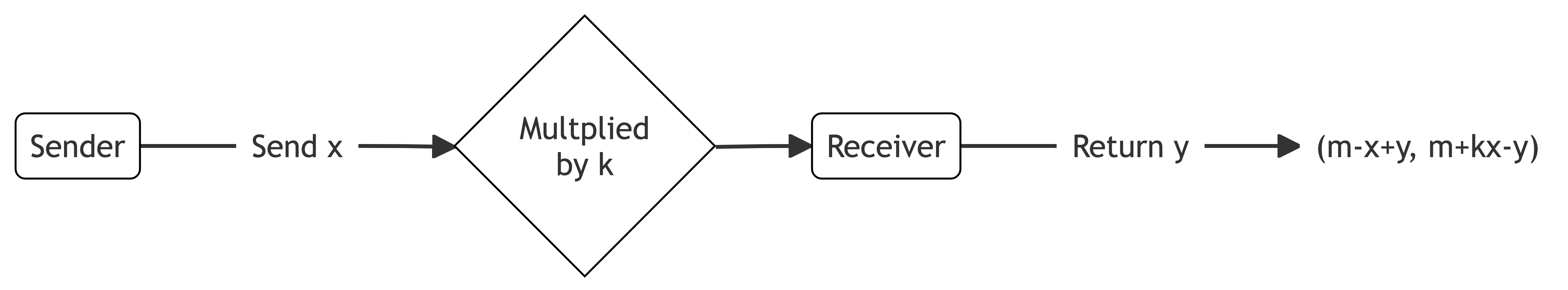

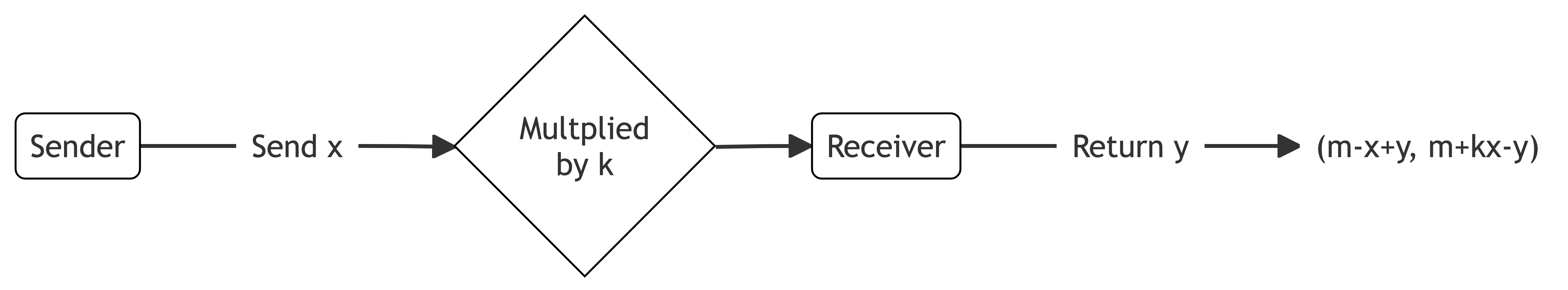

While altruism and inequality aversion explain many observed behaviours, they are not the only types of social preference. Rearranging the inequality aversion model reveals the direct weights people place on others’ outcomes. Where x_i>x_j, agent i places weight of \beta on the other’s outcome and 1-\beta on their own. Where x_i<x_j, agent i places weight of -\alpha on the other’s outcome and 1+\alpha on their own.

Arranging in this way makes the weight given to the outcomes for each agent more transparent. It provides a more intuitive way to consider some distributional preferences.

Example: the trust game

Let’s use this form of the utility function to analyse the outcomes in a trust game, where an investor must decide whether to trust an entrepreneur with their money.

The trust game provides a lens for understanding how social preferences affect economic transactions where success requires sequential cooperation and trust. The trust game captures two key real-world dynamics. First, one party must choose whether to make themselves vulnerable to exploitation by trusting the other. Second, the trusted party must then decide whether to honour or betray that trust.

This structure mirrors some common economic situations. Investors must decide whether to trust entrepreneurs with capital before knowing if they will act in good faith. Business partners often need to commit resources before knowing if their counterparts will uphold their end of the deal. Even simple transactions, like paying in advance for services, involve one party trusting another to deliver as promised.

In the exercises in Section 44.3, I considered a scenario between Linda, a potential investor, and Marco, an entrepreneur. This mirrors common situations where investors must decide whether to trust entrepreneurs with capital, and entrepreneurs must choose between short-term gain and maintaining their reputation. Their choices will depend not just on monetary payoffs, but on how each values the other’s outcomes.

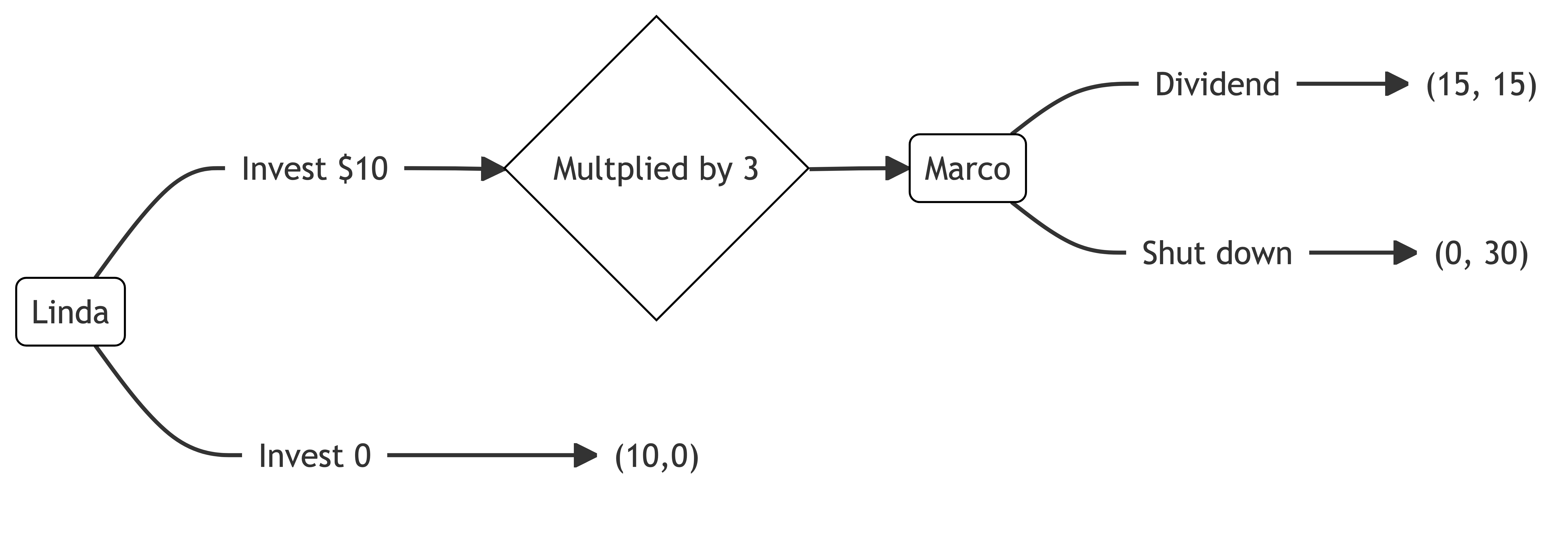

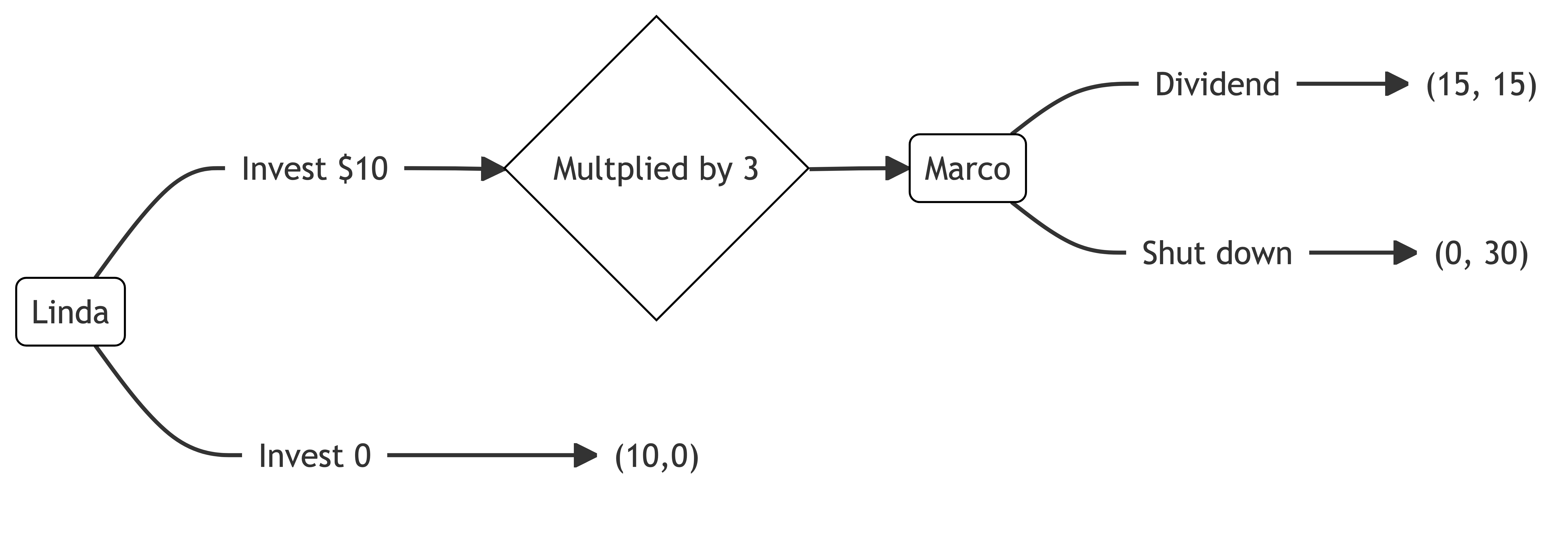

Linda is looking for investment opportunities. She identifies a promising crypto-based start-up created by Marco. Marco is looking for seed funding.

Linda can invest $10.

If Linda invests, her investment will triple in value. Marco can then decide to either shut down the start-up and keep the $30 or maintain the start-up in the market and pay a $15 dividend to each of Linda and himself.

If Linda does not invest, Linda keeps the $10. The start-up gets $0.

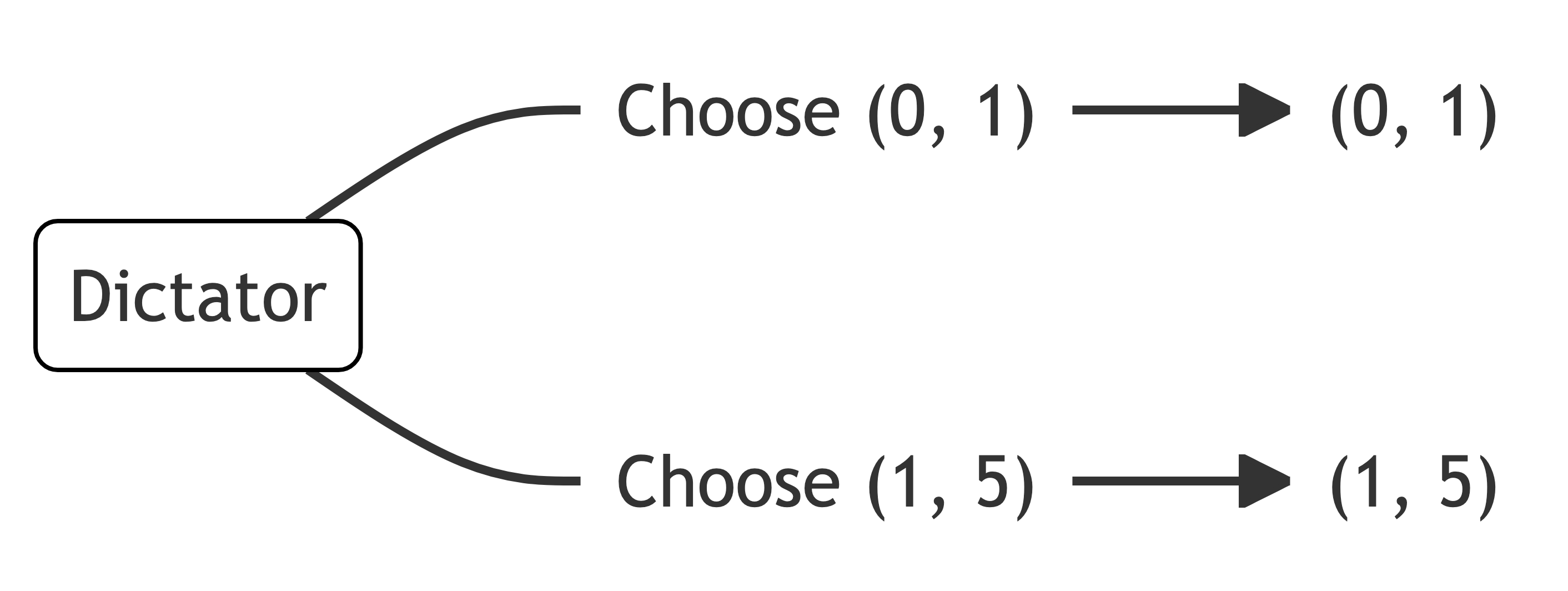

Marco is effectively playing a dictator game. If he were purely self-interested, he would shut down and keep the $30. As a result, a purely self-interested Linda would not invest.

Let’s examine both players’ actions if their utility functions place weight on the outcome of the other. U_L and U_M are Linda and Marco’s utility. x_L and x_M are the outcomes for Linda and Marco.

Linda’s utility function shows moderate concern for Marco’s outcomes:

U_L(x_M,x_L)=\left\{\begin{matrix}

\frac{2}{3}x_M+\frac{1}{3}x_L \quad &\textrm{if} \quad x_L \geq x_M\\[6pt]

\frac{1}{3}x_M+\frac{2}{3}x_L \quad &\textrm{if} \quad x_L < x_M

\end{matrix}\right.

When Linda is ahead, she places more weight on Marco’s payoff (\rho=2/3) than her own (1-\rho=1/3), suggesting significant altruism. When behind, she still values Marco’s payoff positively (\sigma=1/3), but prioritises her own outcome (1-\sigma=2/3).

Marco’s preferences are more asymmetric:

U_M(x_L,x_M)=\left\{\begin{matrix}

\frac{3}{4}x_L+\frac{1}{4}x_M \quad &\textrm{if} \quad x_M \geq x_L\\[6pt]

x_M \quad &\textrm{if} \quad x_M < x_L

\end{matrix}\right.

He shows concern for Linda’s outcomes only when he’s ahead, otherwise focusing solely on his own payoff. This asymmetry reflects a mix of self-interest and conditional altruism.

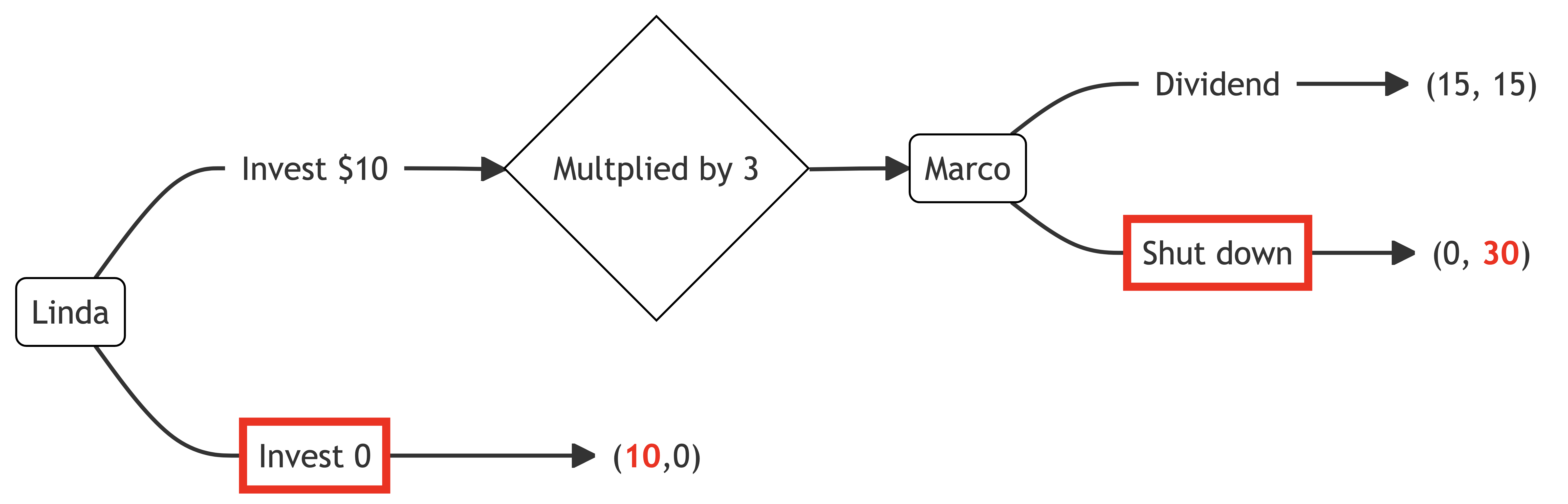

If Marco and Linda know each other’s utility functions, what is the equilibrium with these distributional preferences?

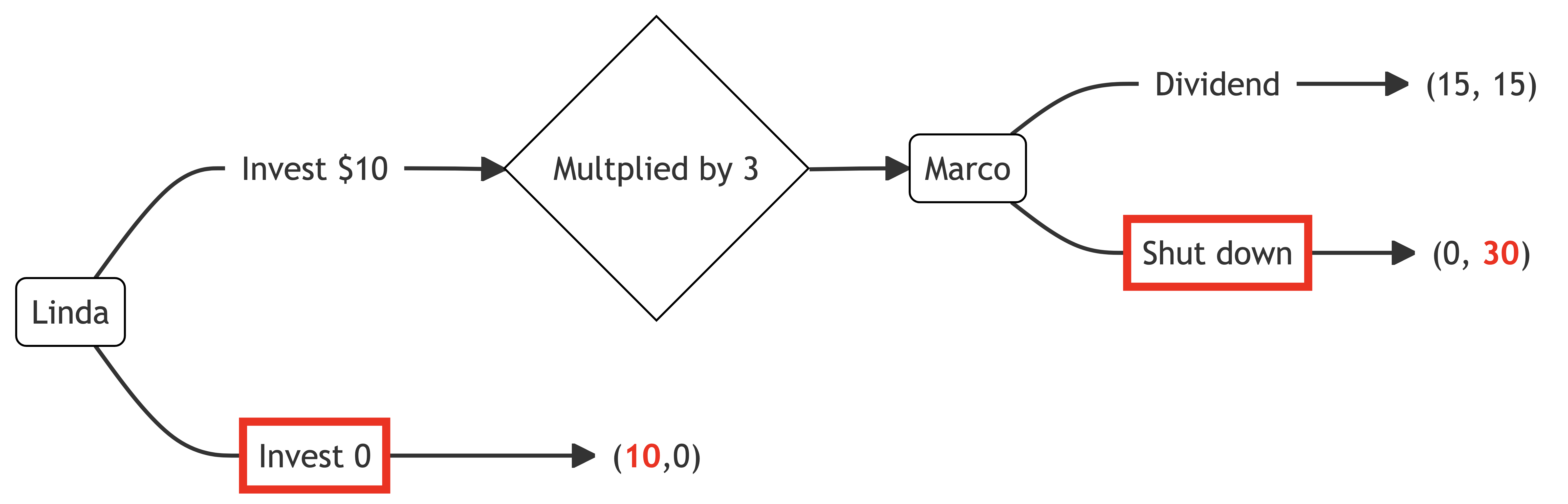

If Linda chooses trust, Marco has a choice between $15 each and $30 for himself. Marco calculates the utility of each option.

\begin{align*}

U_M(15,15)&=\frac{3}{4}(15)+\frac{1}{4}(15)\\[12pt]

&=15 \\[12pt]

U_M(0,30)&=\frac{3}{4}(0)+\frac{1}{4}(30) \\[12pt]

&=7.5

\end{align*}

Marco receives higher utility by paying the dividend to Linda.

We can also calculate Linda’s utility for each of Marco’s options if she chooses to trust.

\begin{align*}

U_L(15,15)&=\frac{2}{3}(15)+\frac{1}{3}(15) \\[12pt]

&=15 \\[12pt]

U_L(0,30)&=\frac{1}{3}(30)+\frac{2}{3}(30) \\[12pt]

&=10

\end{align*}

Linda’s utility is higher if Marco pays a dividend.

For the other node, if Linda does not invest, she will keep $10. Marco will have nothing. Each has the following utility from that failure to invest.

\begin{align*}

U_M(10,0)&=0 \\

\\

U_L(0,10)&=\frac{2}{3}(0)+\frac{1}{3}(10) \\[12pt]

&=3.33

\end{align*}

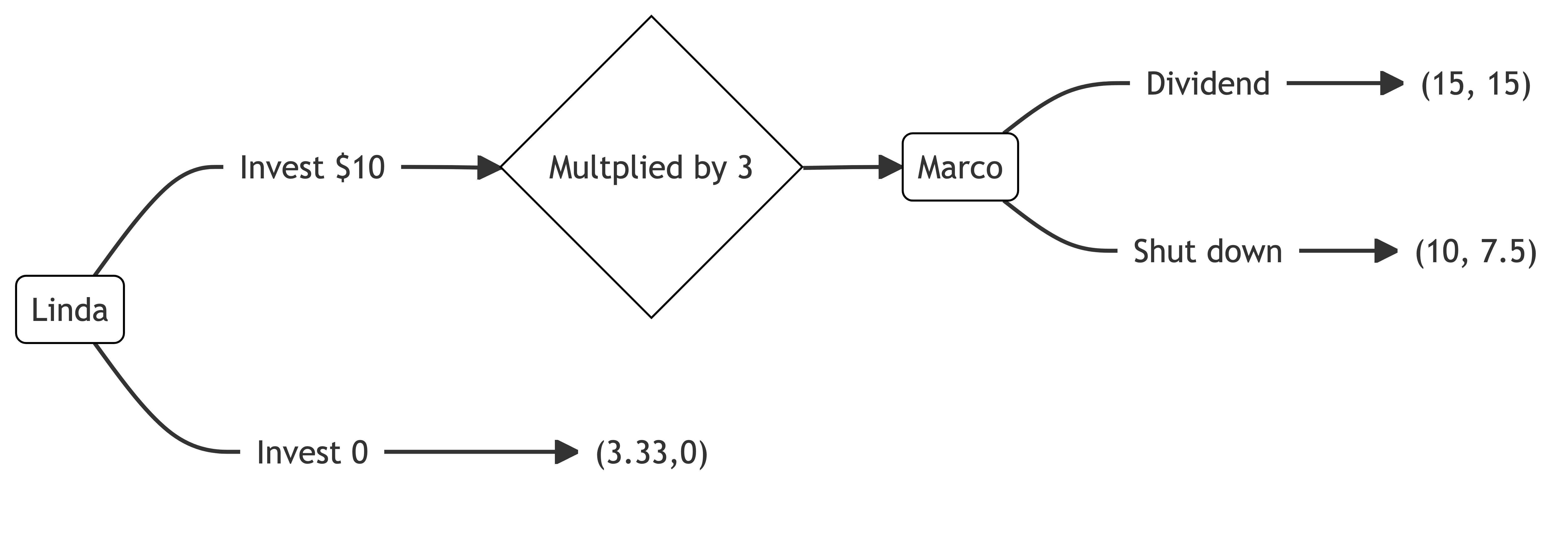

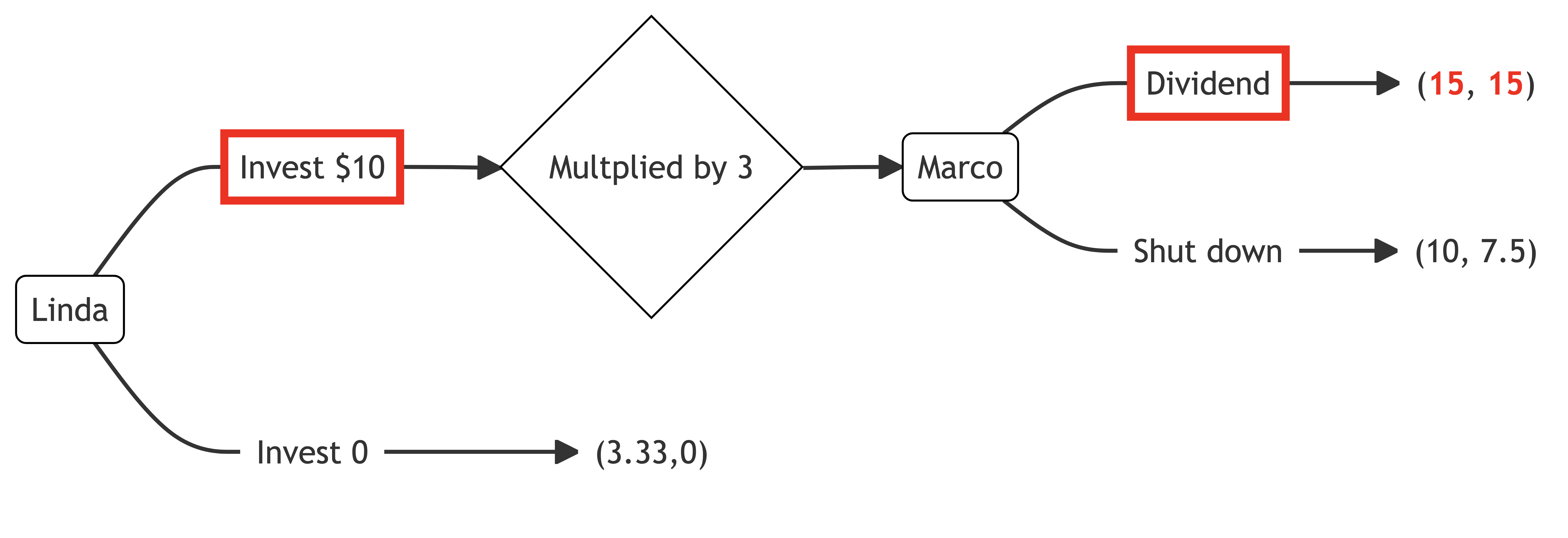

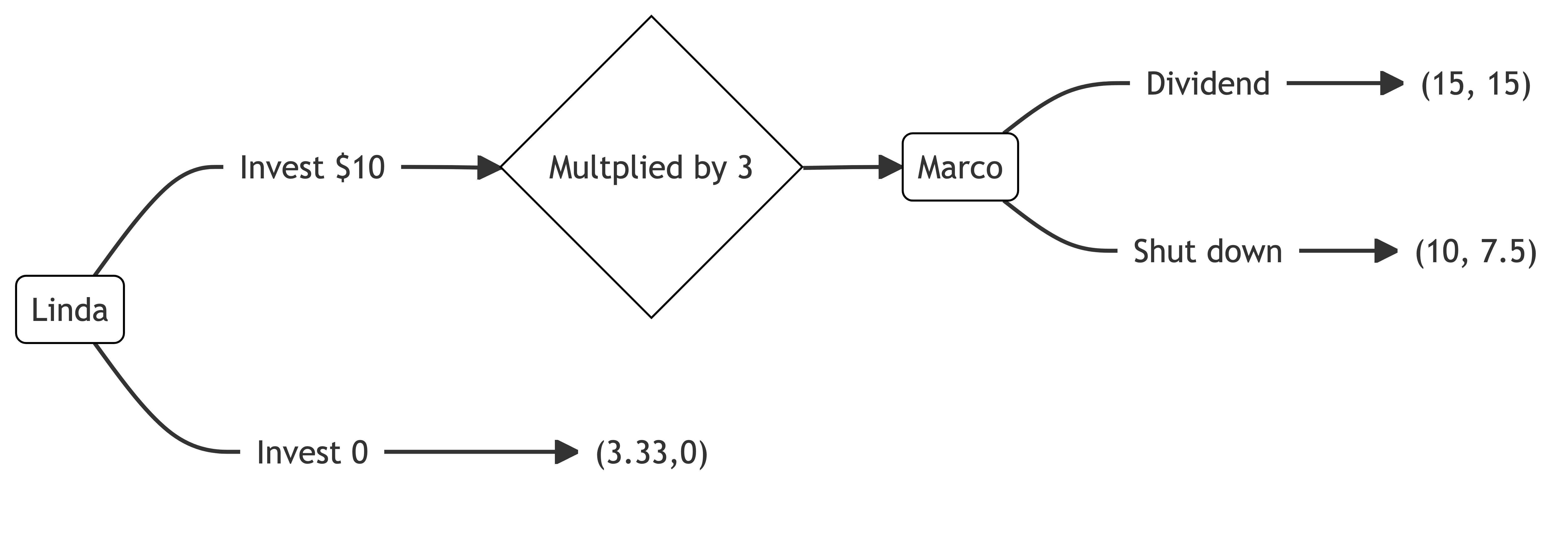

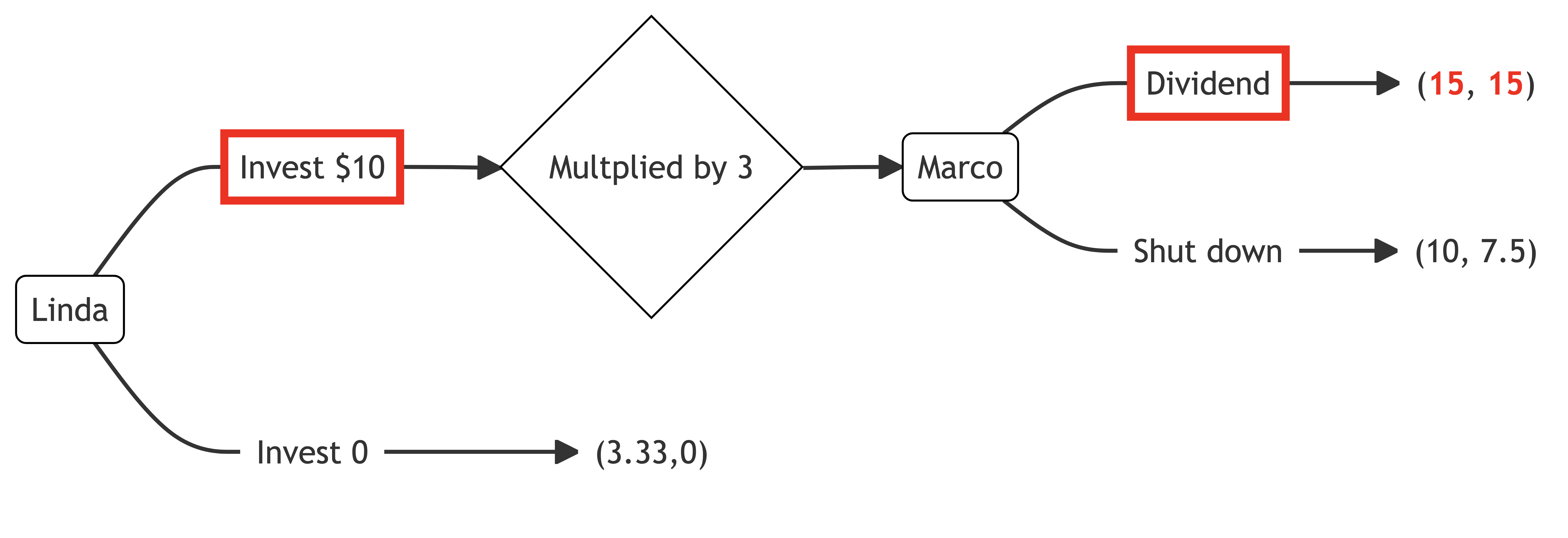

Putting those payoffs into the extensive form of the game, we get the following, with payoffs of (15,15) if Linda invests and Marco returns the dividend, (10,7.5) if Linda invests and Marco does not return the dividend, and (3.33,0) if Linda does not invest.

To solve for the game’s equilibrium, we use backward induction, starting with Marco’s decision if Linda invests.

Marco can return a dividend for utility 15 or shut down for utility 7.5. He chooses to return the dividend. As a result, Linda will invest for utility 15, rather than not invest for utility 3.33. Linda invests.

Card, D., Mas, A., Moretti, E., and Saez, E. (2012). Inequality at Work: The Effect of Peer Salaries on Job Satisfaction.

American Economic Review,

102(6), 2981–3003.

https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.102.6.2981

Charness, G., and Rabin, M. (2002). Understanding social preferences with simple tests.

The Quarterly Journal of Economics,

117(3), 817–869.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/4132490

Fehr, E., and Schmidt, K. M. (1999). A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation.

The Quarterly Journal of Economics,

114(3), 817–868.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/2586885