50 Reputation

Summary

- People care about their social image and reputation, often fearing the stigma associated with selfish behaviour. This concern can influence decision-making beyond purely strategic considerations.

- Andreoni and Bernheim’s (2009) experiment demonstrates this effect: dictators in a modified dictator game changed their offers based on whether the receiver would infer that the offer came from them.

50.1 Introduction

People care about what other people think. They fear the social stigma that can result from “selfish” behaviour.

Partly, this is for strategic reasons. For example, to attract reciprocal behaviour, people may need to be aware of your intentions.

However, there is also evidence that people care about what other people think.

50.2 Example

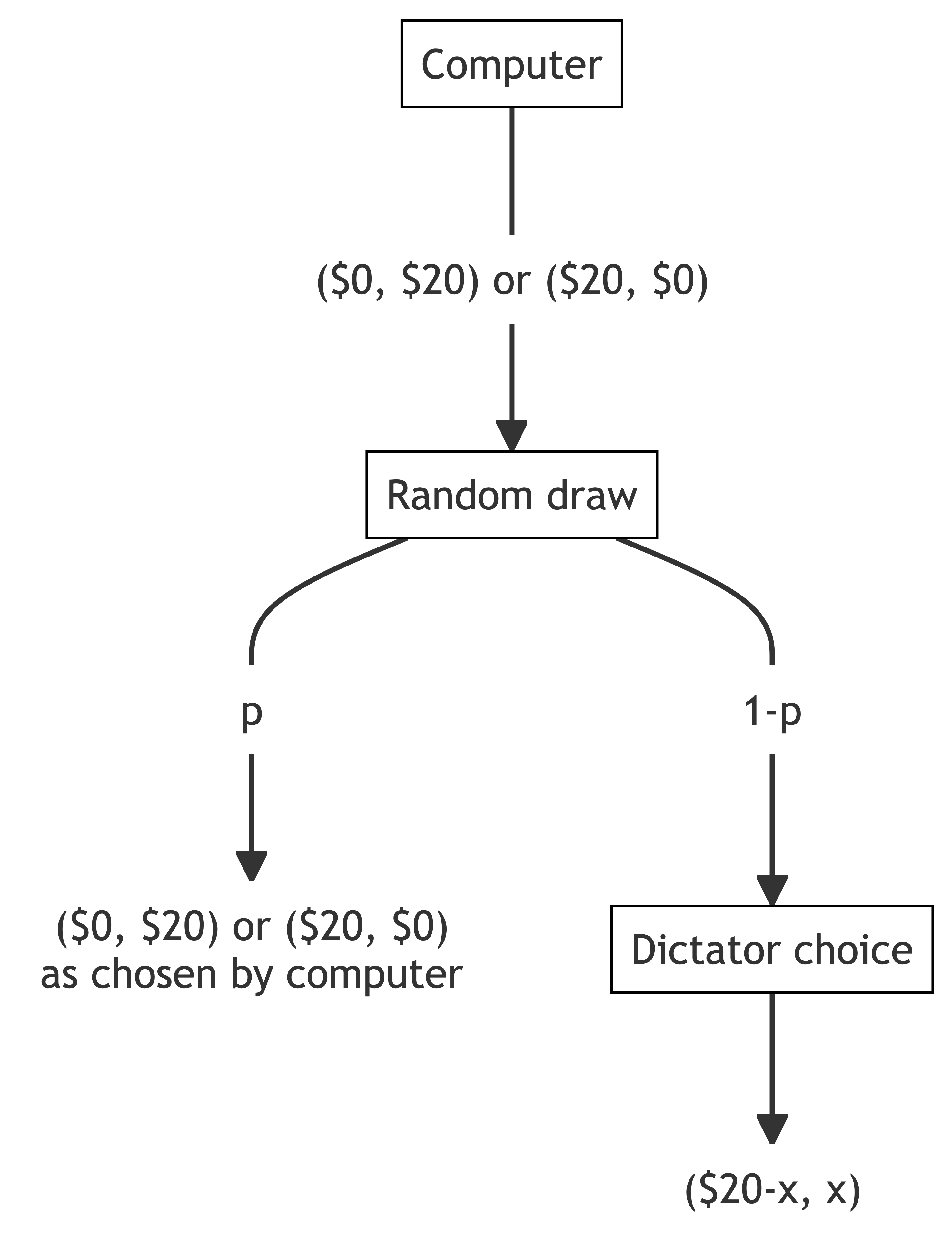

One example of this comes from Andreoni and Bernheim (2009), who ran a non-anonymous dictator game.

Each dictator was endowed with $20.

A computer then chose a distribution between the dictator and the receiver, selecting either ($0, $20) or ($20, $0) with equal probability. The dictator observes the computer’s allocation, but the receiver does not.

The computer’s allocation is then implemented with a probability p. Otherwise, the dictator’s allocation is made. This probability is known to both the dictator and the receiver.

If the dictator’s choice is to be implemented, the dictator makes a split of the $20, offering x to the receiver. The receiver learns only the allocation. They do not learn the dictator’s choice.

Distributional preferences predict that p should not affect the dictator’s choice. The dictator should only think about the situation in which their choice matters.

However, the experimental results did not conform with this prediction. Dictators condition their decision on the common knowledge of p.

This chart shows how offers change with (p) when the computer’s offer of 0 if selected. The x-axis shows p equal to 0, 0.25, 0.5 and 0.75. Each line represents a different bucket of offers. The red line is the proportion of dictators offering 0. The blue line represents the proportion of participants offering $10, a 50:50 split.

For p of 0.5 or 0.75 and a computer allocation of 0 to the receiver, most dictators will offer 0. If the receiver receives a low allocation, the receiver will likely infer it is due to the computer’s decision. They will not blame the dictator.

For p of 0 and a computer allocation of 0 to the receiver, more than half of dictators will offer $10 to the receiver. In this case, if the receiver receives a low allocation, the receiver will infer it is due to the dictator’s decision, not the computer’s.

For a p of 0.25, a slim majority of participants offer zero, with some plausible deniability due to the 25% probability of the offer coming from the computer.

These results suggest the dictator cares about their reputation in the eyes of the receiver.